Stanley Rodriguez holds the painted gourd rattle in his hand. Lifting the instrument with its wooden handle, worn smooth from hours of use, he shakes it to create a rhythm and begins to sing. He’s joined by other singers from his culture in offering prayer for the day, for a fruitful discussion and, later, a safe journey home for all in the conference room overlooking the Pacific Coast at the University of California at San Diego.

Rodriguez and his group, which gathered on July 12 at an indigenous coastal-management conference, are singing in Kumeyaay, one of the world’s most endangered languages. There’re fewer than 150 speakers of Kumeyaay and its sister tongues, Ipaay and Tipaay, out of a total population of 4,250 members of the Kumeyaay bands that originally spoke them.

Kumeyaay is just one of the approximately 40 percent of the world’s nearly 7,100 languages, as catalogued by Ethnologue, that are threatened, endangered or on the verge of extinction. Similarly, UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger places that number at 43 percent. Although the exact number of endangered languages differs depending on how they’re measured (some counts include dialects), the statistics tell the same story: A large portion of the world’s human languages are endangered, just like the species these Indigenous peoples have nurtured.

However, there’s also a movement by indigenous peoples, nonprofits and academics to reverse this trend. They assert that keeping these and other languages alive not only protects cultures, it also supports biodiversity and could hold the key to at least mitigating, if not reversing, climate change.

“The loss of biodiversity is related to the loss of languages,” says Luisa Maffi. She’s the director of Terralingua, a nonprofit based in British Columbia that raises awareness of the concept of biocultural diversity — the link between language, culture and the environment. “Language is not just communications but a repository of knowledge, thinking, ways of life and cultural values of a particular group,” she says.

This focus on biocultural diversity, according to Maffi, helps to preserve both culture and the natural world.

Maffi is one of the 39 authors of The Oxford Handbook of Endangered Languages (2018, $175), a new book showcasing the latest research in preserving languages. The handbook brings together the latest researchers into language loss and its cultural and environmental consequences. Several contributors, including Maffi, discuss the intersections between peoples, ecologies and endemic species.

Maffi says linguists have been concerned about losing languages for decades, but many are only now coming to the realization — “at the last possible moment,” she says — that linguistic diversity loss occurs in the same areas as biological species decline.

To help address this problem, Terralingua has developed a resource it calls the Index of Linguistic Diversity, which helps researchers track where both languages and biodiversity are challenged. “Language, culture, and the environment are inextricably interrelated,” Maffi writes in the introduction to the Index. “In each place, the local environment sustains people; in turn, people sustain the local environment through the traditional knowledge, values, and practices embedded in their cultures and their languages.”

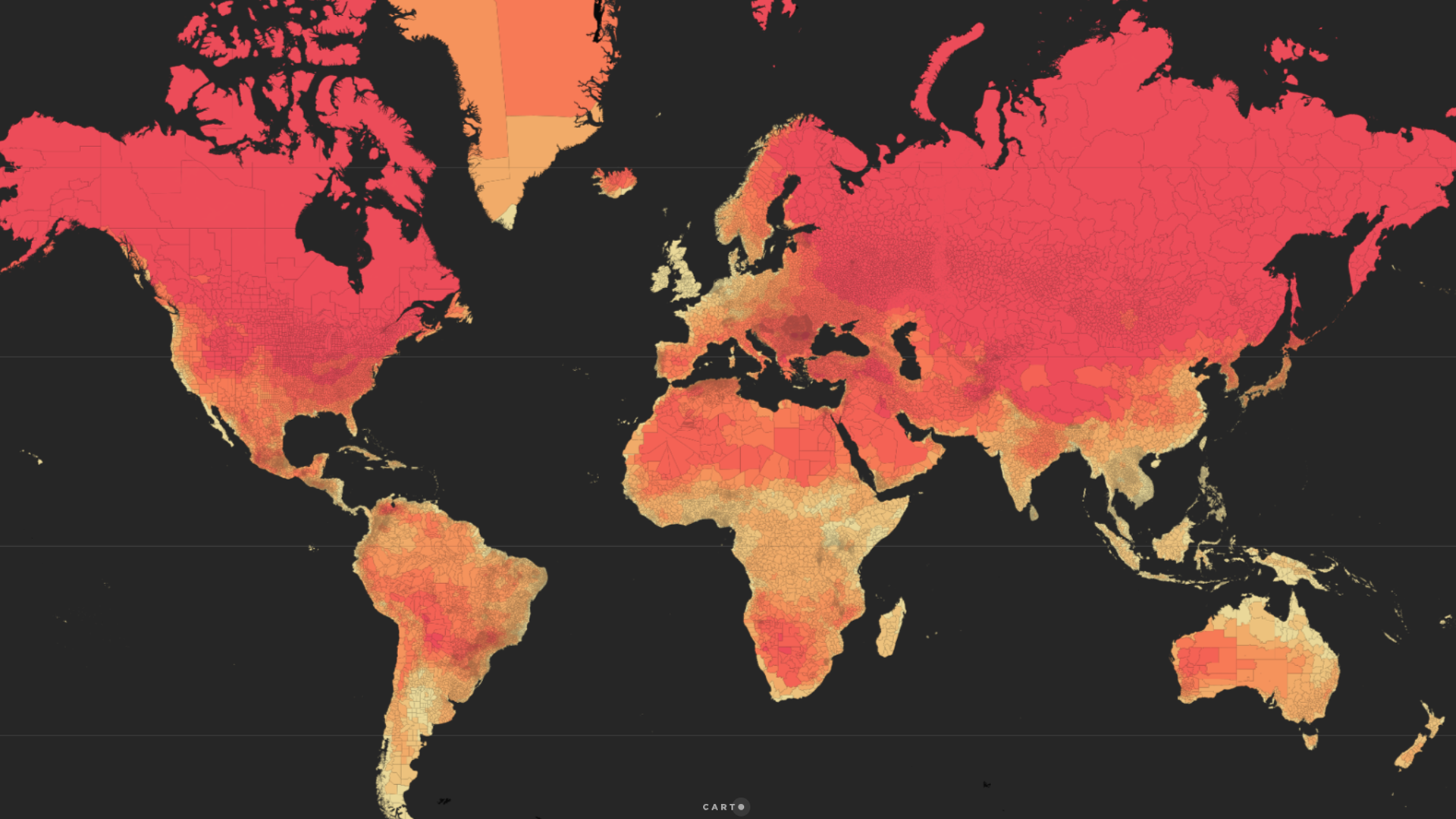

Terralingua has also published a biocultural diversity map showing the correlation between loss of languages and loss of endemic species.

For instance, the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), or honu, declined in Hawaii as Hawaiian language fluency plunged due to a now-repealed law barring its use in schools. However, as Hawaiian has made a comeback since the 1980s, so has the honu’s nesting rate — a 53 percent increase over the past 25 years, although it’s still a federally listed endangered species.

The Americas and Australia — both areas with high numbers of endangered species — have suffered the greatest language losses. Maffi says 64 percent of languages in the United States, 50 percent of Australian languages and 30 percent of Pacific Islander languages have disappeared in the past 45 years. This loss indicates the “mark of colonialism’s effort to erase Indigenous languages in North America and Australia,” she says.

Terralingua’s maps also show how language loss leads to species loss. For example, “Just look at what has happened in Yosemite,” Maffi says. Before Europeans first visited the iconic valley nestled in the western Sierra Nevada, the indigenous Paiutes and Miwoks managed the land to provide food and habitat for several animal and plant species. John Muir admired the park-like setting, which he wrote were “diversified like landscape gardens with meadows and groves and thickets of blooming bushes,” not realizing that these ecological riches were due to human activity and not just an accident of nature.

The Miwoks’ and Paiutes’ careful husbandry over millennia, supported by the languages that detailed techniques and terrain with no direct English translation, fell into disrepair after the people were forced out of the valley. The open groves of oak, willow and sedge gave way to crowded stands of coniferous forests, which grew rank with dead needles, grass and undergrowth. Plants endemic to the valley declined due to decreased sunlight and competition with both endemic and invasive species. Some plants like the Yosemite woolly sunflower (Allium yosemitense) and Tompkin’s sedge (Carex tompkinsii) are now listed as “imperiled” by the California Native Plant Society. Animals such as the Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) have also declined in number.

The loss in language proficiency paralleled Yosemite’s biodiversity decline: Currently, just 400 speak the Northern Paiute language spoken in Yosemite, and only three people speak Southern Sierra Miwok.

The decline of biocultural diversity also works counter to evolution. “Just as with life and nature, the tendency of humans is to diversity,” Maffi says, “but by reducing linguistic diversity, we’re countering that evolutionary tendency.” Just as commercial agriculture relies more on monocultures, which leave the world’s food supply vulnerable to blights, fewer languages create “monocultures of the mind,” she says. “It’s changing the way we think and act.” Commercial pressures are also contributing to “homogenizing” the world, says Maffi.

Other experts support this concept. “Preserving language diversity is an important counterforce to homogenization of the world,” says Teresa L. McCarty, a professor in education and anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles and a researcher in language education and preservation methodologies. She’s also a contributor to the Oxford book, as well as an author and editor on several other books related to language preservation and education. “Diversity of all types is what enables the human race to survive and thrive,” she says. “It’s part of our humanity.”

One group that’s cognizant of the link between language and ecology is the Kumeyaay, whose bands traditionally inhabited a range of climates including valley, mountain, river, desert and oceanfront — Rodriguez even notes that some Kumeyaay villages now lie underwater. “Our songs tell the story of our history, and our language celebrates the environment,” he says. That history is now disappearing.

“If we can’t explain these concepts in our language, we lose the context,” Rodriguez adds. Losing the context, meanwhile, creates a loss of information about past climate and how cultures can adapt to future climate change. One example of that celebration is the Kumeyaay Maat’aam, or year. Each month describes the seasonal change, tracking both solstice and equinox closely. There’s also a mini-season known as Kli’a ‘Emull, the acorn harvest, which occurs during the fall equinox. As the language disappears, so does the knowledge about those ecosystems.

“Language and culture support each other,” Rodriguez says, who adds that the environment is a critical component of both. “Culture and climate are interconnected.”

Can this loss be reversed? The movement to preserve languages, and through them, biodiversity, is a worldwide phenomenon, says McCarty, and the Oxford book is just the latest chapter in an ongoing effort to preserve languages and the information they contain. “To lose language diversity seems totally against everything that supports the survival of humanity,” she says.

© 2018 Debra Utacia Krol. All rights reserved.

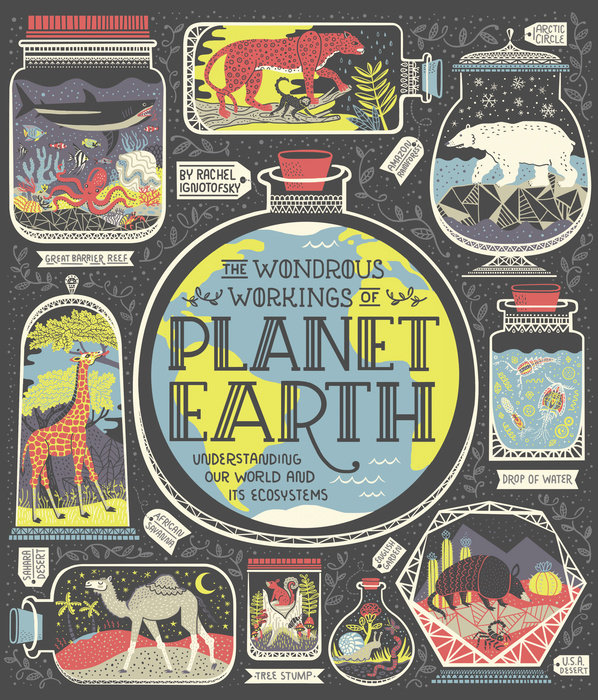

It’s September, which means summer vacation is over, the kids are back in school and it’s time for everyone to learn something new. Here are a ton of new, thought-provoking new books that publishers have scheduled for release this month, with titles covering lions and other endangered species, an important era in environmental history, vital new ideas in agriculture, an iconic tree and a whole lot more.

It’s September, which means summer vacation is over, the kids are back in school and it’s time for everyone to learn something new. Here are a ton of new, thought-provoking new books that publishers have scheduled for release this month, with titles covering lions and other endangered species, an important era in environmental history, vital new ideas in agriculture, an iconic tree and a whole lot more.

The first step for me was discovering the field of literary environmental nonfiction and the work of people like Annie Dillard, Gretel Ehrlich and Terry Tempest Williams. I was lucky to go to a college where I could study environmental science and writing, as well as the overlap of the two.

The first step for me was discovering the field of literary environmental nonfiction and the work of people like Annie Dillard, Gretel Ehrlich and Terry Tempest Williams. I was lucky to go to a college where I could study environmental science and writing, as well as the overlap of the two.

We wanted the long view, so for answers to our questions we went to Shelley Silbert, executive director of

We wanted the long view, so for answers to our questions we went to Shelley Silbert, executive director of