Climate change has been steadily warming the ocean, which absorbs most of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, for 100 years. This warming is altering marine ecosystems and having a direct impact on fish populations. About half of the world’s population relies on fish as a vital source of protein, and the fishing industry employs more the 56 million people worldwide.

My recent study with colleagues from Rutgers University and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found that ocean warming has already impacted global fish populations. We found that some populations benefited from warming, but more of them suffered.

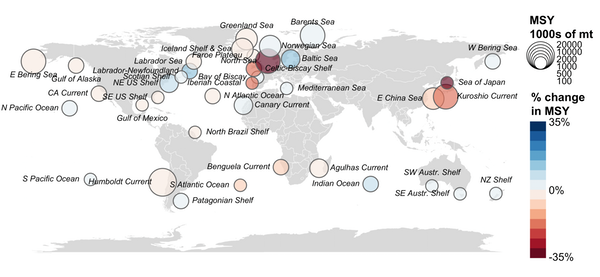

Overall, ocean warming reduced catch potential — the greatest amount of fish that can be caught year after year — by a net 4 percent over the past 80 years. In some regions, the effects of warming have been much larger. The North Sea, which has large commercial fisheries, and the seas of East Asia, which support some of the fastest-growing human populations, experienced losses of 15 percent to 35 percent.

How and Why Does Ocean Warming Affect Fish?

My collaborators and I like to say that fish are like Goldilocks: They don’t want their water too hot or too cold, but just right.

Put another way, most fish species have evolved narrow temperature tolerances. Supporting the cellular machinery necessary to tolerate wider temperatures demands a lot of energy. This evolutionary strategy saves energy when temperatures are “just right,” but it becomes a problem when fish find themselves in warming water. As their bodies begin to fail, they must divert energy from searching for food or avoiding predators to maintaining basic bodily functions and searching for cooler waters.

Thus, as the oceans warm, fish move to track their preferred temperatures. Most fish are moving poleward or into deeper waters. For some species, warming expands their ranges. In other cases it contracts their ranges by reducing the amount of ocean they can thermally tolerate. These shifts change where fish go, their abundance and their catch potential.

Warming can also modify the availability of key prey species. For example, if warming causes zooplankton — small invertebrates at the bottom of the ocean food web — to bloom early, they may not be available when juvenile fish need them most. Alternatively, warming can sometimes enhance the strength of zooplankton blooms, thereby increasing the productivity of juvenile fish.

Understanding how the complex impacts of warming on fish populations balance out is crucial for projecting how climate change could affect the ocean’s potential to provide food and income for people.

Impacts of Historical Warming on Marine Fisheries

Sustainable fisheries are like healthy bank accounts. If people live off the interest and don’t overly deplete the principal, both people and the bank thrive. If a fish population is overfished, the population’s “principal” shrinks too much to generate high long-term yields.

Similarly, stresses on fish populations from environmental change can reduce population growth rates, much as an interest rate reduction reduces the growth rate of savings in a bank account.

In our study we combined maps of historical ocean temperatures with estimates of historical fish abundance and exploitation. This allowed us to assess how warming has affected those interest rates and returns from the global fisheries bank account.

Losers Outweigh Winners

We found that warming has damaged some fisheries and benefited others. The losers outweighed the winners, resulting in a net 4 percent decline in sustainable catch potential over the last 80 years. This represents a cumulative loss of 1.4 million metric tons previously available for food and income.

Some regions have been hit especially hard. The North Sea, with large commercial fisheries for species like Atlantic cod, haddock and herring, has experienced a 35 percent loss in sustainable catch potential since 1930. The waters of East Asia, neighbored by some of the fastest-growing human populations in the world, saw losses of 8 percent to 35 percent across three seas.

Other species and regions benefited from warming. Black sea bass, a popular species among recreational anglers on the U.S. East Coast, expanded its range and catch potential as waters previously too cool for it warmed. In the Baltic Sea, juvenile herring and sprat — another small herring-like fish — have more food available to them in warm years than in cool years, and have also benefited from warming. However, these climate winners can tolerate only so much warming, and may see declines as temperatures continue to rise.

Management Boosts Fishes’ Resilience

Our work suggests three encouraging pieces of news for fish populations.

First, well-managed fisheries, such as Atlantic scallops on the U.S. East Coast, were among the most resilient to warming. Others with a history of overfishing, such as Atlantic cod in the Irish and North seas, were among the most vulnerable. These findings suggest that preventing overfishing and rebuilding overfished populations will enhance resilience and maximize long-term food and income potential.

Second, new research suggests that swift climate-adaptive management reforms can make it possible for fish to feed humans and generate income into the future. This will require scientific agencies to work with the fishing industry on new methods for assessing fish populations’ health, set catch limits that account for the effects of climate change and establish new international institutions to ensure that management remains strong as fish migrate poleward from one nation’s waters into another’s. These agencies would be similar to multinational organizations that manage tuna, swordfish and marlin today.

Finally, nations will have to aggressively curb greenhouse gas emissions. Even the best fishery management reforms will be unable to compensate for the 4 degree Celsius ocean temperature increase that scientists project will occur by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.