Our oceans are a vast, lawless frontier. But this long-exploited, still mysterious realm is central to modern economic life.

About 90 percent of international trade occurs by ship. Oceans provide fossil fuels and then absorb most of the carbon dioxide and heat produced by burning them. Billions of people in the poorest countries rely on the ocean for food and work.

And some of the most brutal forms of economic exploitation take place on the water. Sea slavery and other flagrant human-rights violations are rampant. And industrial-scale overfishing, both legal and illegal, has undermined conservation efforts and pushed prized fish species toward extinction.

This all happens out of view: The average American has little idea what went into putting fish on his or her plate, or where all that plastic packaging will end up. Even governments that try to police the worst abuses are often in the dark.

Thankfully new light is being shined on the problem.

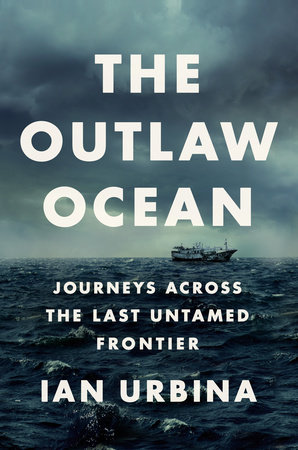

New York Times reporter Ian Urbina has gone to great, dangerous lengths to peel back that veil. First in his “The Outlaw Ocean” series, and now in his new book, The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontiers, Urbina reveals the horrifying conditions and idealistic possibilities of life at sea.

The scope of Urbina’s reporting has been astounding. He’s recounted a harrowing voyage on a massive Thai purse seiner worked by forced Cambodian labor and a months-long pursuit of an illegal fishing boat through iceberg-strewn waters. He’s interviewed whistleblowers about sea slavery and illegal dumping by cruise ships. He’s told of a submarine trip to a Brazilian coral reef that oil companies sought to secretly hurt and travels with a colorful maritime repo man. He’s made visits to a ship that offers abortions near places where they’re illegal and ocean outposts that claim a quirky kind of national sovereignty or illegally trade arms, oil or people.

“For all that adventure, though, the most important thing I saw from ships all around the world, and have tried in this book to capture, was an ocean woefully under-protected and the mayhem and misery often faced by those who work these waters,” writes Urbina in his introduction.

Even when enterprising journalists, activists or regulatory agencies discover and expose some to the worst abuses of our oceans — such as fishing-boat workers getting kidnapped or tricked into brutal, years-long servitude or desperate stowaways summarily executed — there are few effective international mechanisms to right the wrongs.

“Such is the inconvenient truth of globalization: it is based more on market sleight of hand than on Adam Smith’s invisible hand,” Urbina writes. “By outsourcing this task [of staffing fishing boats] to manning agencies, the people who work in the corporate responsibility and human resource offices of the grocery store chains and fish wholesalers further down the supply chain need not try to understand or explain how it is possible that the captains on these boats found workers willing to work for so little.”

Capitalism and its big players treat oceans as an inexhaustible domain for extracting resources and dumping waste, while avoiding national human-rights and environmental-protection laws and standards.

And yet, as Urbina writes, “the ocean was not meant to be a thing we use or a place where we extract resources and dump waste. It was vast habitat that we should leave alone or, better still, protect and help to flourish. Less meant to fill our wallets or stomachs, the ocean was an opportunity to expand our humanity, foster biodiversity, and prove our ability to live in balance with the rest of the planet’s occupants.”

To that end the book concludes with recommendations for ways we can better protect mariners, create a more transparent food-supply system, protect ocean environments from illegal dumping and plundering, and devise a system for monitoring and investigating offshore crimes.

But first we need to open our eyes to the important role of oceans in modern life and summon the political will to be their wise stewards.

“The ocean is outlaw not because it is inherently good or bad but because it is a void, like silence is to sound or boredom is to activity,” he writes. “While we have for centuries embraced and touted the life that springs from these waters, we have tended to ignore its role as a refuge of depravity. But the outlaw ocean is real, as it has been for centuries, and until we reckon with that fact, we can forget about ever taming or protecting this frontier.”

![]()

4 thoughts on “Outlaw Oceans: Exposing Slavery, Overfishing and Other Abuses on the High Seas”

Comments are closed.