Billions of missing crabs in the waters off Alaska are a grim harbinger.

In October the Alaska Department of Fish and Game announced, for the second year in a row, that the Bering Sea snow crab population had plunged so low they had to close the fishery.

Snow crabs were once plentiful in the frigid waters, but researchers calculated that more than 10 billion had vanished from the eastern Bering Sea since 2018. They posited that the crabs had either moved or died. Research confirmed the latter.

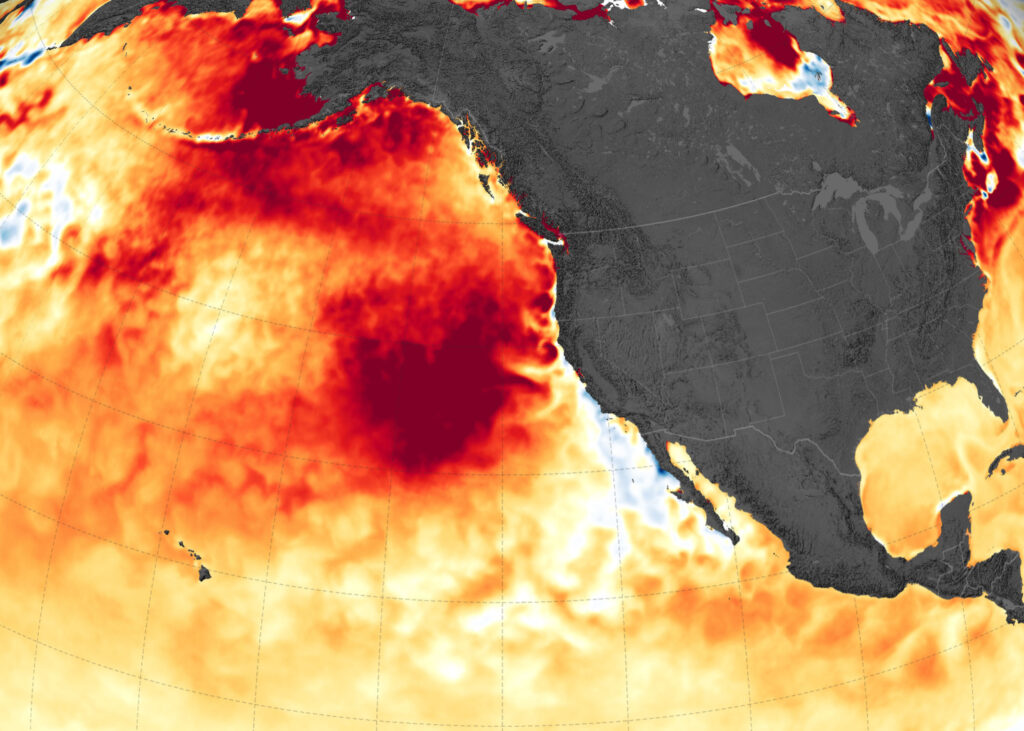

The culprit, the study explained, was a marine heatwave in 2018 and 2019 that pushed water temperatures up — not high enough to kill the crabs outright, but enough to increase the amount of calories they needed to consume. Many crabs couldn’t find enough to eat and starved. Others were eaten by Pacific cod, who were able to extend their range into suddenly warmer waters.

We should take heed.

“The Bering Sea is on the frontlines of climate-driven ecosystem change, and the problems currently faced in the Bering Sea foreshadow the problems that will need to be confronted globally,” the researchers wrote.

As we’ve pumped more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, the ocean has been working overtime, absorbing more than 90% of the excess heat since the 1970s. But the bill for that is coming due.

2023 was the warmest year and on record, and that extend to the ocean, too. There were five consecutive months with global sea surface temperatures hitting record monthly highs. August recorded the highest monthly sea surface temperature anomaly in 174 years of NOAA’s recordkeeping. In addition to rising average global sea surface temperatures, marine heat waves are also becoming more common.

Scientists attributed it to a combination of long-term climate warming and a growing El Niño in the Pacific Ocean, which causes warming-than-usual water temperatures.

“Over the long term, we’re seeing more heat and warmer sea surface temperatures pretty much everywhere,” says Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “That long-term trend is almost entirely attributable to human forcing — the fact that we’ve put such a huge amount of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere since the start of the industrial era.”

Changes Ahead

High water temperatures can throw ecosystems out of balance, as was the case with a persistent marine heatwave in the northern Pacific Ocean from 2013 to 2016 called “the Blob.” The warm waters fueled a bloom of toxic algae, which poisoned a host of marine life ranging from shellfish to sea lions. It also caused a shutdown to the crab fishery to protect human health.

When catching crabs was deemed safe again, fishers set their traps in the same area where humpback whales were feeding on anchovies. The turf war caused a record number of whale entanglements.

High water temperatures don’t just alter ecosystems; they can also cause direct mortality. Corals, for instance, have a symbiotic relationship to the algae that lives on them and gives them their color. But when water temperatures get too hot, the animals expel the algae, turning a whitish color. If this bleaching is prolonged, they succumb to disease and starvation.

Between 2014 and 2017 heat stress caused bleaching in 75% of tropical reefs around the world, resulting in mortality at nearly 30% of them. Even deep reefs, once thought protected, are now vulnerable. Researchers found coral bleaching in the Indian Ocean 300 feet below the surface.

This summer a marine heat wave scorched Florida’s waters, with one location recording triple digits in August. The ideal temperature range for most corals is between 73 and 84 degrees Fahrenheit. But temperatures well above that caused widespread bleaching and mortality on Florida reefs.

“This year’s bleaching event is proving to be more than many of even our hardiest corals can cope with,” the Coral Restoration Foundation reported in August. “Cheeca Rocks has experienced almost total bleaching and widespread mortality already. Sombrero, Newfound Harbor, Eastern Dry Rocks, and Looe Key have also succumbed to the heat.”

The loss of coral reefs threatens the homes and foods of 30% of marine fish and countless other species, while also leaving coastal communities more vulnerable to storm waters.

On the Move

For some marine species, survival will depend on being able to move if they’re unable to adapt to the rate of warming or prolonged ocean heat waves. Already we know that some haven’t been able to keep up.

A 2019 study in Nature found that local extirpations related to warming were twice as common in the ocean as on land. A likely contributor is that fish and other marine ectotherms — animals that don’t have internal mechanisms for regulating their body temperatures — live closer to the upper limit of tolerable temperatures. Nowhere is this truer than for fish that live in the tropics.

Water temperature is important for regulating basic functions for fish, such as metabolism, reproduction and growth. A study published in May in Global Change Biology looked at how 115 species of marine fish were responding to rising ocean temperatures. They found the majority of those populations were shifting their ranges toward the cooler water of the poles. This was especially true in the Northern Hemisphere, which has seen faster rates of warming.

Where species adaptations allowed them to go deeper, they did that too. And it may be a last resort for Arctic fish that are limited in poleward expansion.

The ecological implications for these changes are vast.

“While relocation to cooler water may allow these species to persist in the short-term, it remains to be seen how food webs and ecosystems will be affected by these changes,” says Shaun Killen, a professor at the University of Glasgow and study co-author, of the research. “If the prey of these species don’t also move, or if these species become an invasive disturbance in their new location, there could be serious consequences down the road.”

Even more serious will be if climate warming remains unchecked and we continue along a high-emissions path. If that’s the case, we’re likely to see mass extinction on par with those in Earth’s history, found researchers of a 2022 study in Science. The highest risk of extinction is for species living at the poles, but the biggest drop in species diversity will happen in the tropics.

Concerted global action to tackle climate change could make a significant impact in curbing this impending loss.

“Reversing greenhouse gas emissions trends would diminish extinction risks by more than 70%, preserving marine biodiversity accumulated over the past ~50 million years of evolutionary history,” the researchers wrote.

Billions of snow crabs would thank us.

![]()