A lot has changed since 2008. That’s when Ken-ichi Ueda turned his master’s project at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Information into a website called iNaturalist, which allowed people to post pictures and help identify species.

Since then iNaturalist has grown as technology has evolved — first becoming a mobile app in 2011 and eventually adding more sophisticated machine-learning models to streamline the identification of plants and animals.

It’s also grown in numbers. When Scott Loarie — now codirecting with Ueda — joined in 2010, he was the 477th user. Today the platform has almost 3 million users across the world who have recorded 150 million observations of 430,000 species. That’s made iNaturalist the leading source for biodiversity data for the majority of species — data that’s been used in more than 4,000 scientific papers.

That growth has come amidst a changing world. Global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, and species extinctions are occurring at 1,000 times the natural rate. iNaturalist’s data on hundreds of thousands of species can help us better understand some of the ways global changes are affecting individual species — and spur action for better protections, says Loarie.

The Revelator spoke to him about the conservation potential of iNaturalist, the biodiversity questions artificial intelligence can help answer, and what he’s learned from his 27,000 observations posted to the platform.

How has iNaturalist evolved?

I met Ken-ichi in the fall of 2010, two years after he started iNaturalist. At that time I was a postdoc at Stanford, and my research was focused on trying to scale and find new ways to generate and deal with biodiversity data. I immediately quit academia and got involved.

We ran iNaturalist as an LLC for five years, and then in 2011 we launched the first mobile app. In 2014 the California Academy of Sciences invited us to join them as an initiative of the museum. We were at Cal Academy for three more years, and then National Geographic also got involved. We ran another six years as a joint initiative between Cal Academy and Nat Geo. At the end of that contract, everybody realized it was a good time for us to spin off as an independent nonprofit organization, [which we did in July].

Initially iNaturalist was a website, which was combining some photo-sharing things that you could do on sites like Flickr with taxonomic labeling. Increasingly it’s been something that people are experiencing using on their mobile devices. When we launched, the idea that everybody would have a camera and a GPS in their pocket wasn’t a reality. Now obviously that’s totally changed, and I think a huge amount of iNaturalist’s growth has been on the backs of that.

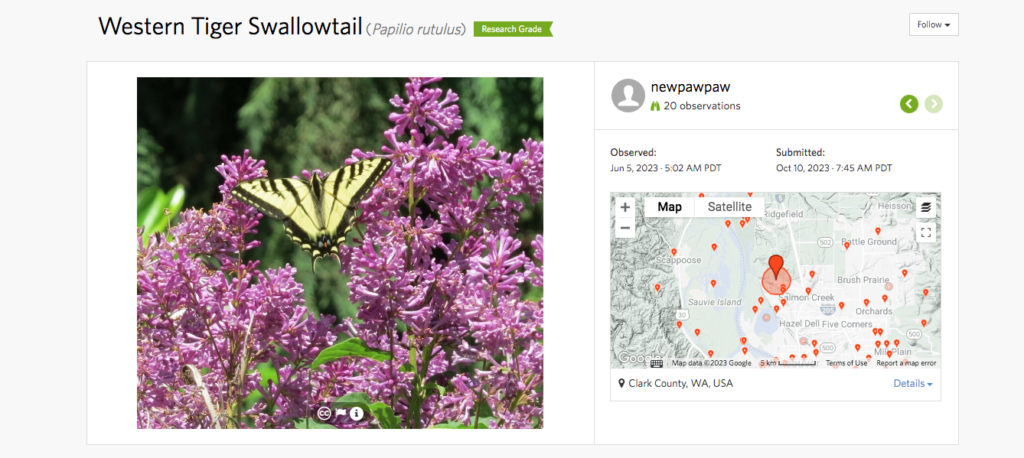

Secondly, when iNaturalist started it was all crowdsourcing. You would post a picture of a butterfly and then you’d have to wait for someone in the community to say, “Hey, this is a western swallowtail.” But then in 2017 we were approached by a bunch of machine-learning researchers who were interested in facial recognition computer-vision work. They said, “You have the biggest data set of labeled images of living things. We would love to do some more research on this.” We realized we were in a position to use our own data to train the artificial intelligence to help recognize species automatically.

The AI is really just a synthesis of the expertise that’s already in our own community.

What can the platform help people do?

Most people think of iNaturalist as a place that gets species identified. A typical use case is that you’re in your backyard, you see this butterfly that interests you and take out your phone and take a picture of it. The iNaturalist app will identify it and tell you this is a western swallowtail.

What excites me more about that is that you can share that observation with the global community on iNaturalist, which can give you some context. They can help with the identification. A lot of times artificial intelligence isn’t perfectly accurate. They can also tell you something interesting about it, “Hey, this is really weird. These aren’t normally found this time of year.” And it’s that interaction with the community where a lot of the learning happens.

iNaturalist has become this really important source of biodiversity data. At the moment it’s producing most of the biodiversity data for most species around the globe. It’s an important tool for generating the biodiversity data that we need to help come up with solid conservation strategies and outcomes. But we’ve also realized that just as important is that what we’re doing is also connecting people in nature and getting them excited about what’s in their backyards.

You personally have 27,000 observations recorded on the platform. What have you learned?

I think that the ecosystem that you’re in wherever you are is such an important lens. It’s so exciting for me when I go visit a place I’ve never been before to just think about what kind of things live there.

It’s funny you mentioned the number of observations because when I had kids and I had less time to go out and find new things and go to remote places, I’ve become a much larger identifier on iNaturalist. I have many more IDs than I have observations. And those are IDs I’ve made for other people.

It’s helped me vicariously live through what other people are seeing. All of a sudden, I can be in South Africa and see what kind of interesting creatures are showing up in the intertidal zone and how that differs from going around the corner to Mozambique. I think it just taps into this lifelong interest I’ve had in geography and biogeography.

How can iNaturalist help drive conservation?

Our main goal is to make sure that iNaturalist is a tool for conservation impact. The three ways that we’re doing that are by connecting people to nature, which changes their hearts and minds. That whole saying that “you conserve what you love, and you love what you understand,” I believe is true. I think that by getting people to get to know a butterfly in their backyard, they’re more likely to stand up for that butterfly in any sort of local conservation. Effective conservation often happens from the bottom up. It comes from local land-use policy and local government action and things like that.

Secondly, just by generating all this data and getting this data into the hands of the scientific community through publications, that’s where a lot of the policy and the advocacy happens at a different level. We know at least 4,000 scientific papers have been published using iNaturalist data.

newpawpaw, iNaturalist (CC BY-NC 4.0 DEED)

The third way is that this community isn’t just monitoring biodiversity — they’re also taking steps to steward the land. We see a lot of local naturalist groups who use iNaturalist to do a “bioblitz,” which are these monitoring events where people come together and see how many species are in a certain area. But they’re also taking steps to improve the habitat. Maybe they’re removing invasive species or bringing back native plants to help pollinators.

Are you seeing users recording information about how climate change and extinction are affecting ecosystems?

Every day we’ll see a paper published or some article in the popular media about one of three big changes. The first is that native species are eroding away. The classic one is the pika at the top of a mountain that has nowhere to move. The range of the pika is getting smaller and smaller every year as the planet gets warmer.

The second is that climate refugee story, which is that all of a sudden we’re seeing species off the coast that have never been seen there before — it’s the march of climate refugees moving as the climate changes. The third isn’t just a climate change story, but we see invasive species show up and really have an impact.

I think the climate change story has turned conservation on its head in some really important ways. The conservation plan used to be that we had to protect these pieces of land. If we can get enough of these species and these pieces of protected land, our job is done.

But now we have to have enough capacity to monitor these species as they’re shifting with the climate and hopping from one piece of land to another to make sure we don’t lose any on the way.

We’ve been using machine-learning tools to synthesize iNaturalist data to try to get at some of biogeography questions, such as: Can we really detect if a species is showing up at a weird time of year or a weird area, or a species is actually eroding away, or a new invasive species is showing up, or climate refugees are moving?

I think that’s really exciting because it combines our mission, which is really to have conservation impact, with some of the things that we’ve shown we can do with computer vision, which is take this data and use it to train these really complicated machine-learning models to pull out some really interesting insight.

It’s a much more dynamic problem, and I think it demands a lot more real-time information, which iNaturalist is really good at collecting.

Previously in The Revelator:

Are Wildlife Identification Apps Good for Conservation?

![]()