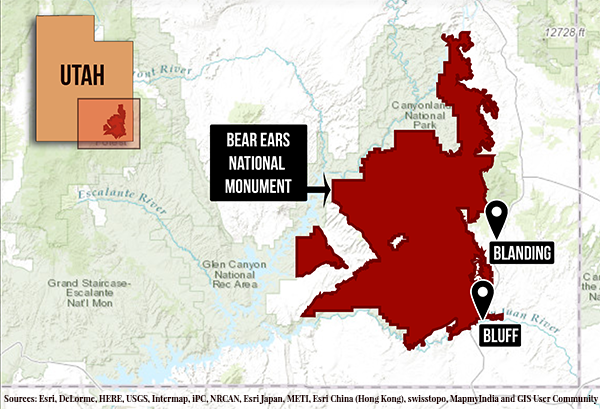

BLUFF, Utah — When it comes to the fight over Bears Ears National Monument, the stark differences in attitudes toward the monument designation between residents of Bluff and nearby Blanding are literally 15 centuries apart.

The roadside signs welcoming travelers to each community located along U.S. 191, one of the nation’s most beautiful highways, succinctly sum up the difference between the two communities.

In a respectful nod toward the ancient settlements that first appeared along the banks of the San Juan River, Bluff’s welcome signs declare that the unincorporated community of about 300 was founded in 650 A.D.

Twenty-three miles north, on a windswept mesa, the city of Blanding welcomes travelers with signs proclaiming its motto, “Base Camp for Adventure,” and stating that it was established in 1905.

Although Mormon pioneers founded both communities, Bluff has shed its ultra-conservative past and has become an intellectual mecca noted for its preponderance of PhDs and archeologists. Residents overwhelmingly hailed President Barack Obama’s proclamation last December creating the 1.3 million-acre Bears Ears National Monument.

“When people are educated and learn to look at other opinions, they are not closed minded,” says Jackie Warren, who works at a Bluff resort and has owned a home in the community for the past 20 years. “I think that’s what you are finding here in Bluff.”

On the other hand, Blanding remains steeped in its deep Mormon heritage. The alcohol-free community has a striking dearth of restaurants and retail stores that creates a depressed downtown pockmarked with vacant buildings. A handful of motels, however, are generally full at night and lodging is relatively expensive.

Most of Blanding’s 3,000 residents adamantly oppose the monument designation and are encouraging President Donald Trump to rescind it as soon as possible. Front lawns prominently display signs opposing the monument, and cars and trucks frequently carry anti–Bears Ears decals in their back windows.

Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke announced earlier this month that Bears Ears should be downsized, but he provided no indication of how much of a reduction he will recommend to the president later this summer. Last April Trump issued an executive order requiring Zinke to review all national monuments designated in the past 21 years greater than 100,000 acres in order to determine if they should be revoked or downsized.

Blanding Embraces Its Past in Opposing Bears Ears

To many in Blanding, getting rid of Bears Ears won’t come soon enough.

“It’s an absolute disaster,” says Jerry Murdock, a longtime Blanding resident who manages Canyonlands Lodging, a website that books vacation homes and cabins.

“In order to save Bears Ears and the lifestyle here, they need to rescind the monument,” he says in a lengthy, rambling telephone interview. “There is no reason to take 1.3 million acres and turn it into a monument when 98 percent of it was already protected.”

Murdock claims that the majority of American Indians in southern Utah oppose the monument but cites no polling to support this claim. He says that tribal leaders who requested President Obama create the monument have not been truthful to their constituents about future access to the land.

Many American Indians forage for plants, hunt for game and collect firewood from the public lands that are now part of the national monument. Murdock and others in Blanding say that monument managers will cut off access.

“They have been fed a line of baloney and that is not going to change,” Murdock says.

Perpetuating the claim that American Indians will be denied access to the land persists, despite the fact that Obama’s proclamation creating the monument addresses this concern. The proclamation creates the Bears Ears Commission, made up of representatives of five area tribes.

The proclamation requires the Department of Agriculture, which oversees the U.S. Forest Service, and the Department of the Interior — which manages Bureau of Land Management property, as well as the National Park Service — to “meaningfully engage with the (Bears Ears) Commission” in developing and revising management plans. The goal is “to ensure that management decisions affecting the monument reflect tribal expertise and traditional and historical knowledge.”

Murdock’s anti-monument attitude echoes the city of Blanding’s official position. In July 2016 the city passed a resolution opposing the monument, declaring it would be “unilateral and unwarranted Presidential designation.”

Blanding City Councilman Robert G. Ogle says in an email that the biggest complaint about the monument designation comes from many in the community who believe “they were not consulted” in the monument decision. “The voice of the local citizens has been minimized,” he adds.

Ogle notes that San Juan County is Utah’s largest county, and federal and state governments control 92 percent of its land. Blanding is the largest community in the county. “Simply put,” Ogle says, “the national monument designation is a land grab to generate greater control.”

Like others in his community, Blanding businessman Joe Lyman, currently serving his third term on the Blanding City Council, turns to a far-right fringe analysis to buttress his anti-monument stance.

Lyman, a descendent of Mormon pioneers who founded Bluff in 1880 after a harrowing trek through the rugged mountains, provided The Revelator with a copy of a report written by J.R. Carlson of Stillwater Technical Solutions of Garden City, Kansas, which was presented to the San Juan County Commission in October 2016.

Carlson’s report claims, incorrectly, that the president doesn’t have the authority to proclaim a national monument under the Antiquities Act of 1906, and that the 43 grazing allotments on Bear Ears National Monument are lands that are not “owned or controlled” by the federal government and therefore not eligible for monument inclusion.

Carlson, the executive director of the Kansas Natural Resource Coalition — an alliance of county governments that engage with federal agencies on natural resource policies — argues in the document that “for purposes of a monument designation, grazing allotments (districts) are a limited-fee, surface title property, and as a result such lands are not owned or controlled by the Federal government.”

There is no widely accepted legal basis to support Carlson’s claim, which is often cited by ranchers seeking to assume control of federal land. The federal government has been leasing federal land to ranchers since passage of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934.

The Act instituted a permitting system to be issued by the federal government for all public rangeland, where for the first time in federal land-management history, fees could be charged in exchange for grazing rights, according to a 2015 Montana Law Review article on the legal framework for transferring federal public land to states.

The article concludes that unless Congress legislates the “disposal of federal public lands, federal lands will remain federal, regardless of which state makes the demand.” In other words, unless Congress transfers ownership of grazing land to ranchers, the property remains under federal control.

Carlson also claims that when Congress in 2014 “reauthorized” the Antiquities Act and moved it under Title 54 National Park Service Preservation Statutes, it eliminated the president’s power to declare national monuments.

“In placing the AA (Antiquities Act) under Title 54, Congress removed any potential for the AA to be considered a stand-alone, executive prerogative,” his report states.

Carlson fundamentally misstates the intent of Title 54, which had no impact on the meaning of the Antiquities Act. Title 54 “did not create new law or change the meaning or effect of existing law,” according to the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Spurious legal arguments aside, Lyman says Blanding has long relied on the tax base created from grazing, mining and timber harvesting on federal lands, including Manti-La Sal National Forest, that are now included in Bears Ears National Monument. He worries the national monument designation will reduce economic development opportunities.

“Continued multiple use of the land is vital to our way of life and our economic survival,” he says. “An increase in seasonal tourism is no replacement for a diverse and healthy economy.”

Bluff Looks Ahead to Protecting Bears Ears

Steve Simpson points to a mound of dirt across the parking lot at his Twin Rocks Café and Trading Post in Bluff. “That’s an unexcavated ruin,” he says. “You can’t go in any direction without finding antiquities.”

There are an estimated 100,000 archeological sites scattered across the Bears Ears cultural landscape, according to the Bears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s national monument proposal submitted to Obama in 2015. Many have been looted over the last 150 years, but countless more remain undisturbed, hidden beneath the soil, in caves and remote canyons.

“I have spent most of my life in this area,” he says. “The pressure on these sites is extreme. Sites where you could once find huge pot shards everywhere, now they are basically sterile.”

Simpson, a tax attorney by training, says most of the people living in Bluff support the national monument and embrace a tourist-based economy that they believe is far more sustainable than relying on the boom-bust extractive industries that have historically underpinned the regional economy.

“You have Bluff, which is a liberal community, right in the middle of an extremely conservative, extremely LDS (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints) area,” he says. “The position of Bluff doesn’t mesh well with the folks in Blanding.” Simpson also knows quite a few people who are opposed to the monument. Many of them are Mormon pioneer descendants, he says, and have strong ties to the land that their ancestors settled in the late 19th century.

There is resentment, Simpson says, that a huge part of what they see as their back yard is now being set aside as a national monument — particularly since it was at the request of American Indian tribes that were forcibly removed from much of their traditional lands, including Bears Ears, more than 150 years ago.

The resentment toward American Indians by the local population was readily apparent during the debate leading up to the monument designation. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman told Navajo leaders that they “lost the war” and have no right to comment on public land management. Ranchers in San Juan County were also telling American Indians to “get back on the reservation.”

For some American Indians, the overt hostility of some monument opponents has resulted in an unofficial boycott of Blanding.

Woody Lee, an American Indian who has worked for years on the monument designation with the Salt Lake City nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah, says Blanding’s negative attitude is scaring off business.

“I live approximately 4 to 5 minutes from Blanding,” Lee says. “Now, why am I not going to Blanding? Well, because the town is not so welcoming.”

Lee says he will travel several hours to Cortez, Colo., or Farmington, N.M., to go shopping rather than spend money in Blanding. He finds it ironic that Blanding cites negative economic impact from Bears Ears while ignoring its less-than-welcoming attitude toward American Indians.

“It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out where to go,” he says. “So now they are jumping up and down about their economy. They are the ones who messed it up.”

Simpson takes a less harsh attitude about Blanding’s opposition to the monument. “I don’t feel it’s a dislike of local Native American people, or a disrespect of Native American people. I think it is more a feeling of possession. ‘We are here. Our ancestors worked this land. We are emotionally invested.’”

At the same time, Simpson says, those opposed to the monument “overlook the Native American spiritual connection to the land. They are overlooking the fundamental idea that this is just not my land. The fact that I live in Bluff doesn’t give me superior right to the land.”

The two fundamental arguments that monument opponents cite — they were not involved in the monument decision and the designation is a land grab — don’t sway Simpson.

Nearly all of the 1.3 million acres of Bear Ears were already federal land, with 109,000 acres controlled by the state of Utah. Obama’s proclamation requests that Utah enter into negotiations to trade the state land within the monument for other federal land in Utah. Utah, so far, has refused and instead enacted a resolution in February requesting that the monument be rescinded.

Monument opponents, Simpson says, also had opportunity to express their views to local, state and federal representatives, including former Interior Secretary Sally Jewel, who held a contentious public hearing on the monument proposal in July 2016 in Bluff.

“To say there was no opportunity for public input is absolutely wrong,” Simpson says.

Bluff is also home to Friends of Cedar Mesa, an environmental group working to protect the monument’s countless archeological resources and stunning landscape.

Josh Ewing, executive director of Friends of Cedar Mesa, credits the fact that five American Indian tribes set aside their longstanding differences and worked together to prepare a comprehensive proposal for the monument that Obama subsequently supported.

His organization, at first, supported efforts to find a legislative solution to debate over Bears Ears. But when that failed, he says, a presidential monument proclamation became the best option.

That won’t be enough, though, if the monument designation ends up in court and the federal government doesn’t allocate sufficient funds to protect the monument from an already significant increase in tourism, Ewing says.

“This is a place where government is not going to be the solution,” he says. “It’s going to have to come from philanthropy, volunteers and hard work on the ground.”

Moving forward, his group is stepping up its efforts to protect resources on the ground by hiring additional employees and promoting a campaign to protect the area’s archeological treasures.

He knows that his group is facing an uphill battle to protect the monument, particularly given the fierce opposition from the state and local governments to its designation. But he remains optimistic and isn’t going to focus on trying to change opponents’ minds.

“The folks against the monument would have been against it no matter who proposed it or how it came about,” he says.

An avid rock climber, Ewing left a corporate job in Salt Lake City to move to Bluff in 2012. He and his wife, Kirsten, are passionate about protecting the Bears Ears cultural landscape that the Trump administration so far has taken a negative approach to protecting.

“Anywhere else, this would be a national park, even if you didn’t have the archeology,” he says.

Previously in this series:

Beyond Division: American Indians Unite to Create Bears Ears

National monument proclamations such as Bears Ears NM (and the Grand Staircase-Escalante NM 20 years ago) would not be necessary if Utah politicians had not been so resistant to wilderness designation on public lands and national forests. Wilderness proposals have been around since the 1980s, but with the exception of a few areas such as the Dark Canyon Wilderness (that includes only a part of Dark Canyon) nothing has been done in southeastern Utah for more than 30 years.