Welcome to the first edition of “Turning Points,” our new column examining critical moments in environmental history when change occurred for the better — or worse.

More than 1,000 people lined the banks of the Kennebec River in Augusta, Maine, on July 1, 1999. They were there to witness a rebirth.

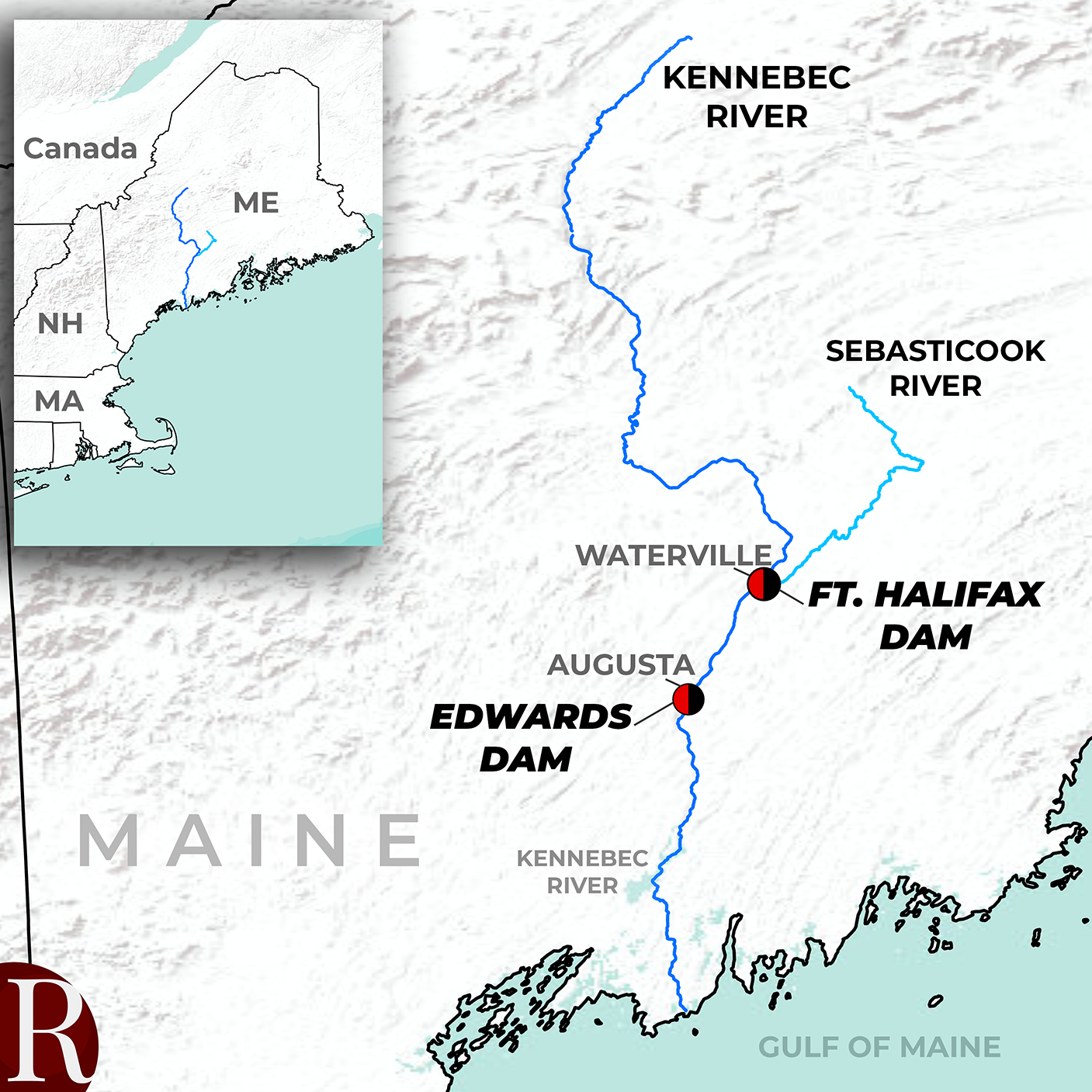

The ringing of a bell signaled a backhoe on the opposite bank to dig into a retaining wall. Water trickled, then gushed. The crowd erupted in cheers as the Edwards Dam, which had stretched 900 feet across the river, was breached. Soon the whole dam would be removed.

The Kennebec hadn’t run free here since 1837.

Those who advocated for the dam’s removal promised that devastated fisheries would return, and the city of Augusta would benefit from new recreational opportunities and a revitalization of the riverfront.

They were right. But it wasn’t just Augusta where change was felt.

The removal of Edwards Dam became a pivotal moment in the history of the environmental movement and river restoration in the United States. It was the first functioning hydroelectric dam to be removed — and the first time the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ever voted, against the wishes of a dam owner, not to relicense a dam.

But most importantly the demolition signaled a shift in thinking about how we balance environmental and economic interests — and that had a ripple effect.

“It was the first big dam that came out that demonstrated to the country that our rivers had other values beyond industrial use,” says John Burrows, director of New England Programs for the Atlantic Salmon Federation, which was a key player in the dam-removal effort. “It helped folks recognize that our rivers, which we’ve not taken good care of for several hundred years, could be a different asset for communities. And for society.”

Killing a River

Building the Edwards Dam was never a popular idea. Even in the 1830s there was concern that the robust fisheries of the lower Kennebec River would be wiped out. But the cheerleaders of industrialism prevailed, and the dam was built in 1837 to bring power to local mills.

The consequences were immediate.

The dam’s construction shut the door on the migration of nearly a dozen sea-run fish species that used to swim up more than 40 miles from the Atlantic Ocean in search of prime spawning habitat in the Kennebec and its tributaries.

“The river was transformed from being a thriving producer of millions of fish such as shad, herring, striped bass, Atlantic salmon, sturgeon and alewives and supporting a wide cornucopia of other species ranging from otters to eagles — into a wastewater drainage system,” Jeff Crane, a dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Saint Martin’s University, wrote in a paper published in 2009.

Within a few years, the alewife run on the Sebasticook River, a tributary of the Kennebec just upstream from the dam, was gone. Where once you’d been able to catch 500 salmon a season in Augusta, by 1850 you were lucky to get five. The state reported that the shad industry there was completely lost by 1867. And the sturgeon catch on the lower Kennebec declined from 320,000 pounds a year before the dam to just 12,000 pounds a year by 1880.

Within a few years, the alewife run on the Sebasticook River, a tributary of the Kennebec just upstream from the dam, was gone. Where once you’d been able to catch 500 salmon a season in Augusta, by 1850 you were lucky to get five. The state reported that the shad industry there was completely lost by 1867. And the sturgeon catch on the lower Kennebec declined from 320,000 pounds a year before the dam to just 12,000 pounds a year by 1880.

In the 1900s the river’s problems got even worse. The Kennebec River became a dumping ground for toxic waste from paper mills and municipal sewage. Log drives from the upstate timber industry choked the river’s flow, and declining oxygen levels from sewage caused major fish kills. By the 1960s no one wanted to fish or swim in the Kennebec anymore.

Brian Graber, who now works as the senior director of river restoration at American Rivers, grew up in Massachusetts and spent his summers in a family cabin outside Augusta. The Kennebec River of his childhood wasn’t a place to have a good time — or even to live.

“I think what struck me the most as a kid was that all the buildings in downtown Augusta were facing away from the river and were either boarded up or just didn’t have windows at all along the river,” Graber recalls.

But things began to gradually improve after the passage of the national Clean Water Act in 1972.

The state of Maine spent $100 million on water-treatment facilities between 1972 and 1990 to clean up the river and meet modern environmental laws. Improvements in water quality triggered a new interest in expanding river restoration. The Kennebec wasn’t hopeless after all.

But one hurdle remained.

Thinking Big

During the 1980s efforts to improve fish passage at dams and water quality in the river continued. Even though many environmental groups thought dam removal was the best ecological hope for restoring the Kennebec, few believed it was a winnable campaign.

“At that time removal of dams was a pretty outlandish concept and most people who we were interacting with did not see us prevailing,” says Pete Didisheim, senior director of advocacy at the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

The only other talk of dam removal happening then in the United States was across the country on Washington’s Elwha River. (The Elwha’s two dams wouldn’t end up being removed, however, until 2011 and 2014.)

In 1991 the owners of the Edwards Dam, Edwards Manufacturing Company, applied for a 50-year renewal license to operate it. The newly formed Kennebec Coalition jumped in to convince the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the agency in charge of the relicensing, to deny that permit. The coalition was made up of the nonprofits American Rivers, the Atlantic Salmon Federation, the Natural Resources Council of Maine, and Trout Unlimited and its Kennebec Valley chapter.

“People began to not only imagine what dam removal would do for the benefit of the fish, but also what it would do for the benefit of the town if they had a functioning, free-flowing river running through it,” says Andrew Fahlund, currently senior program officer at the Water Foundation, who was working for American Rivers during the push for dam removal.

The coalition had a strong argument. The dam produced only 3.5 megawatts of power, providing less than 0.1 percent of Maine’s electricity. It employed only a few people and was aging and unsafe, having been breached numerous times. It blocked critical upstream fish habitat, including the migration of endangered sturgeon.

And a restored fishery would bring economic as well as ecological benefits — profits that could be more widely shared than those of the small company that owned the dam.

But taking down a functioning hydroelectric dam for the benefit of fish had never been done before.

“Initially the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission staff issued their proposal that the dam should be relicensed,” says Burrows. “It took our organizations doing a lot of work with some experts to actually demonstrate that the ecological values of removing the dam outweighed the power generation.” The coalition produced 7,000 pages of documentation on the impacts of the dam and the economic importance of a restored fishery.

At the same time, they worked to educate the public and earned national attention and the support of Maine’s governor, Angus King, who said that the removal of the dam would help the Kennebec “reclaim its position as both an economic asset and an ecological miracle.”

Dam proponents countered that removal would be too expensive and would cause riverbank erosion, bring more downstream floods and lower property values for those along the riverfront.

But in 1997, after mounting evidence from the coalition, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission voted to deny license renewal. It ordered that the dam be removed. People campaigning for removal were ecstatic, while dam owners across the country were shocked.

This was the first time the commission used its authority to deny a permit against the wishes of a dam owner. And it hasn’t been done since.

It wasn’t just the commission’s ruling that was groundbreaking; it was also the first time a dam was coming down on the main stem of a river and not a smaller tributary, which Graber says was a significant achievement. “It was a pivotal moment for us to build a national movement to take out dams,” he adds.

The battle wasn’t yet won, though.

It took another year for a negotiated settlement to be reached with the dam owner, conservation groups and federal and state agencies that managed to stave off the threat of lengthy lawsuits from Edwards Manufacturing Company.

Much of the funding for the removal ended up coming from Bath Iron Works, a downstream shipbuilder that was expanding its operations into prime sturgeon habitat. The company paid into the dam-removal settlement as part of its environmental mitigation.

The decision had far-reaching impacts.

“The success of this effort would serve as an example of what could be accomplished for other river restoration activists around the nation, thereby contributing to the dramatic growth of dam removal efforts and fisheries restoration projects,” wrote Crane.

A River Reborn

The removal of Edwards Dam in July 1999 turned out to be a chance for Augusta to rebuild its relationship to the river.

“Like most towns in New England of that era, their backs had been turned to the river for more than 100 years,” says Fahlund, who was on the banks that day. He remembers it feeling electric and the atmosphere festive — music played, commemorative T-shirts were sold and reporters from around the world showed up.

It was also, he says, a day of mixed emotions for some residents. The dam had been a piece of the town’s history for more than 160 years, both infrastructure and monument, but part of the campaign to remove it had been to counter the notion that dams are meant to last forever.

That echoed beyond the town limits. “Even though it wasn’t a huge dam, it had somewhat of a seismic impact on people’s thinking about dams that they’re not necessarily permanent fixtures in eternity on the landscape,” says Didisheim.

As soon as the dam came down, the river rebounded. Fish immediately had access to 18 more miles of habitat, up to the town of Waterville at the mouth of the Sebasticook River. Atlantic sturgeon began to swim past the former dam site, and alewife and shad soon returned. Within a year seals could be seen chasing alewives, a type of river herring, 40 miles upstream from the ocean.

And with alewives coming back, so did everything that eats them — river otters, bears, mink, bald eagles, osprey and blue herons.

But the best indicator of the ecosystem’s recovery was the resurgence of aquatic insects like mayflies and stoneflies, which signaled improved water quality.

“They all rebounded and the diversity just skyrocketed,” says Fahlund. “And so we knew something great was happening and that it was going to lead to everything we had hoped.”

Within a few years the river began to meet higher water-quality standards.

“The water… is now that much healthier because it’s no longer sitting still and dead,” stated a 2009 editorial in the Kennebec Journal Morning Sentinel. “Instead, it bubbles and spills its way downstream across rediscovered gravel bars and river ledges, collecting and absorbing oxygen as it moves toward the ocean. The river is alive in a way it hasn’t been for generations.”

The benefits spread to the community as well. A park and trails were built along the waterfront. “People are out on the water, mostly paddling a kayak or canoeists,” says Graber. “The downtown is starting to make use of the river more. The buildings that have been redeveloped are now using the river as an amenity. The river’s really just come back to life both for humans and the ecology.”

Ripple Effect

The success didn’t end in Augusta, though. The removal of Edwards Dam ignited efforts to take out the next obstacle up-river, the Fort Halifax Dam on the Sebasticook River in Waterville. After eight years of work that dam was removed in 2008, further extending habitat for native fish.

“We have species like sturgeon, striped bass, rainbow smelt and other key sea-run species which now have access to all of their historic habitat in the watershed,” says the Atlantic Salmon Federation’s Burrows.

The removal of both dams, in conjunction with active stocking of alewives into lakes and ponds upriver and in other parts of the watershed, has helped the river herring population rebound dramatically. The number of alewives returning to spawn jumped from 78,000 in 1999 to 5.5 million last year.

And the downstream estuary has reaped rewards, too.

When those billions of juvenile river herring leave the freshwater lakes and rivers, they head for the sea and may spend between three and five years in the marine environment. There they serve are a food source for everything from cod and haddock to whales and seals.

“They are really a kind of keystone ecological species for the Gulf of Maine,” says Burrows.

The river herring are also a valuable source of bait for commercial lobstermen, who in recent decades have had such a deficit in securing local supplies that they’ve had to turn to importing bait from southeast Asia, introducing a host of new environmental problems and costs.

“We’ve now got the largest river herring population on the east coast of the United States, maybe even on the entire eastern seaboard of North America, but that population could easily be three, four times what it is now,” says Burrows. “And so we’re continuing to work on restoring more habitat and we’re hoping to see those populations continue to increase.”

Didisheim says an estimated 27 million alewives have reached spawning habitat since the Ft. Halifax Dam was removed, and none of it would have happened without first removing the Edwards Dam.

The Edwards Dam also helped propel a large restoration project a couple hours northeast of Augusta on the Penobscot River. Conservation groups worked with the dam operator on the Penobscot to increase hydropower generation on some other dams and then remove a series of lower dams that opened up more than 1,000 miles of river access for fish, especially critically endangered Atlantic salmon.

While that project was being developed, its proponents could point to the Kennebec River restoration as an example of what could be achieved.

“The Kennebec River activists and city and state leaders did not have the advantage that later river restoration activists would have — namely, the Kennebec River restoration itself as powerful example of how quickly river restoration could work and how successful it could be,” wrote Crane. “This is the one reason that the Edwards Dam removal is so important; it showed other communities the process required and how successful it could be.”

A Movement Grows

Dam removals followed outside Maine. When the Edwards Dam was removed, about five dam removals were taking place nationwide each year. Last year it was 80. Since Edwards, more than 1,100 dams have come down.

Many of these have been small dams, but there have also been high-profile projects, like the two Elwha River dams that were the largest dam-removal project so far in the world.

The removal of the 125-foot-tall Condit Dam in 2011 on the White Salmon River, a tributary of the Columbia River in Washington, was a big step in aiding threatened salmon and steelhead. The Condit was removed because adding modern requirements for fish proved to be uneconomical — it was cheaper to remove the dam than build fish passage.

Overall there’s been a shift in public thinking about dams over the past two decades. “It’s not just something that conservationists and environmentalists are advocating for anymore,” says Amy Souers Kober, communications director at American Rivers. “Dam removal also makes sense for economic reasons and public safety in a lot of cases.”

That includes Bloede Dam on the Patapsco River in Maryland, where nine people have drowned, she says. Efforts to remove the dam there began in September.

There are also a number of big projects on the horizon, including on the Middle Fork Nooksack River, which Kober says is the number-one salmon-recovery project on the Puget Sound that conservationists hope will help struggling Southern Resident killer whales.

And all eyes are on the Klamath River as plans come together to remove four dams in 2021 in what would become the largest dam-removal and river-restoration project in the world.

Dam-removal proponents don’t think we need to take out all of our dams, and of course we couldn’t. The United States has more than 90,000 dams, and many still serve crucial functions. But where dams have been removed, the past two decades have shown the environmental results are unparalleled.

“There’s no faster or more effective way to bring a river back to life than taking out a dam,” says American Rivers’ Graber. “That’s why we focused on it for 20 years. It’s a win for environmental reasons, public safety and a relief from liability for dam owners.”

Ultimately, dam removals are much bigger than the dams themselves, says Kober. “Dam removals are really stories about people reclaiming their rivers.”

Those stories started with the Edwards Dam.

![]()

1 thought on “How Removing One Maine Dam 20 Years Ago Changed Everything”

Comments are closed.