A football field full of moss-covered bald cypress trees gone every 90 minutes, along with delicate purple irises, tide-tattooed barrier islands, and marsh grasses. That’s the common estimate of how much land Louisiana’s coast is losing — the fastest rate of land loss in North America. From 1932 to 2016 almost 1.2 million square acres of land disappeared, and more vanishes every day.

The state faces a confluence of threats. Accelerated sea-level rise due to climate change, subsidence, oil and gas drilling, and relentless tropical activity constantly loosen the sediment and allow the land and whatever was growing on top of it to be carried away in the current.

Today the Barataria Bay — one of the major outlet regions of the mighty Mississippi River and one of the areas worst affected by erosion — is muddy but still blue. Small fishing vessels dot the horizon as anglers haul in their catch of the season. A sticky heat beats down 11 months of the year, allowing tropical species like orchids and even some carnivorous plants to thrive alongside egrets and tree frogs.

All of it is at risk as the shore slowly melts into the Gulf of Mexico.

“The Bay has gotten larger. As land eroded away, many smaller and distinct bodies of water disappeared,” says Rosina Philippe, an elder of the Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha Tribe who lives near the Bay.

Terry McTigue/NOAA (public domain)

Since the 1980s a collective of scientists, state lawmakers and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have brainstormed ways to revive and rebuild the lost wetlands. In 2012 Army Corps officials released the master plan for the largest, most expensive, and most controversial potential solution: the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project.

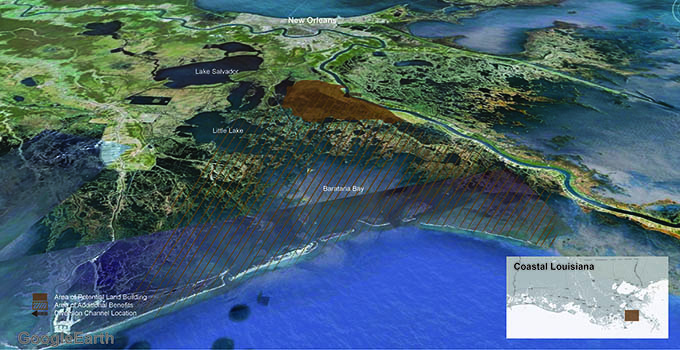

The diversion would re-channel part of the Mississippi into swamps and marshes of the Barataria Basin near the towns of Ironton and Lafitte, about 25 miles south of New Orleans. This, officials argue, would allow the natural process of the river to bring in more freshwater — and with it the sediment necessary to rebuild land.

After an initial five years of construction, this diversion would build and sustain 10,000 to 30,000 acres of coastal swamps and marshes over a 50-year period, according to Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

Ten years after its proposal, the project looms on the horizon. Already five of its nine permits and certifications are complete. The Army Corps is expected to release its final Environmental Impact Statement in September, the approval of which would likely trigger consent for the final three permissions.

But like every coin and every story, there are at least two sides. Some say the diversion project is necessary to benefit future generations, while others argue that alternative projects could build more land.

Rising Water, Vanishing Culture

Eugene Turner, a coastal scientist professor at Louisiana State University, expresses concerns that diverting the Mississippi into the Barataria Basin would immediately raise water levels — as much as two to three feet when the water is flowing. That would, in turn, force much higher storm surges through the Bay during tropical activity.

That’s on top of the current risk from climate change. If nothing is done and the planet continues its current warming trajectory, coastal Louisiana could see sea-level rise of 2.8 feet by 2100, according to estimates from the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program’s 2020 climate adaptation report. The coast would also be more susceptible to flooding during tropical storms and hurricanes, which are expected to rush ashore with higher intensities.

The storm surges, both from the diversion and projected sea-level rise, would threaten people who live nearby, including several Louisiana coastal Indigenous Tribes such as the Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha, traditional hunters and trappers who rely on the life within the swamps and marshes for survival. Even though the main goal of the diversion is to restore wetlands, many Tribe members oppose it. If the project goes through, the communities could lose their livelihoods.

Rosina Philippe, of the Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha Tribe in Grand Bayou, is the president of First People’s Conservation Council. The council’s mission is clear: “to make federal and state conservation programs with the First Peoples for the restoration of our land, water and air through education and demonstration.”

“If the true intent is to protect, preserve and restore lands and habitats, listen to the people who inhabit these lands,” she says. “We are a water people. Our lives are integrated with all that the waters provide. We belong to these waters; it’s our lifeblood.”

The Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha, like many who reside on the coast, have long since adapted to life in the surge zone. Homes in the village are already raised as high as 13 feet as a storm surge precaution.

But 13 feet may no longer be enough. The diversion-risen water levels would also likely flood the only roadway that allows vehicles to access the village, says Philippe, rendering it impassable. Medical emergencies and evacuations would be more difficult and dangerous. The people may be forced to adapt further — or relocate.

Many expressed concern that these Indigenous groups have been ignored in the diversion project’s planning — and in many other aspects of Louisiana government.

“People don’t realize that they’re out there,” Turner says. “They’re just invisible in a lot of ways, and that’s been the historical problem.”

Some nontribal members have fishing camps in the Barataria Basin. The rickety wooden houses full of sleeping cots, nonperishable food and antique fishing decor teeter on the water’s edge, lifted by support beams. Many of the shacks — which families have passed down for generations and provide anglers with a place to crash during the busiest seasons — would wash away.

Coastal scientist John Lopez agrees that the project would raise water levels. He’s been involved with the diversion project since the beginning, first with the Army Corps, then as the lead for coastal projects at Pontchartrain Conservancy, a nonprofit focused on environmental sustainability in Southeast Louisiana. He recently left the conservancy and started his own consulting business, but he still says this project is necessary to benefit future generations.

The people who live out there, “frankly already have problems with storms and even high tides,” he says.

The area is unsuitable to build a levee, so some Barataria Basin communities have tried to mitigate the impacts of storm surge and already-rising sea levels by placing boulders in the way of the water. But Lopez fears that won’t be enough.

“I’ve never seen someone come up with a way to protect those communities from major storm surge,” Lopez says.

An Alternative Approach

When Turner isn’t writing scientific articles on alternative land-building projects, he’s working with three Indigenous communities in the Barataria Basin, including the Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha, to backfill the canals.

“Backfilling and closing canals should be the first project and will serve as a complement to other proposed projects, even the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project,” Philippe says.

Generally, when crews build canals for oil and gas production, they discard the sediment and soil onto the banks. Turner and his colleagues take these creatively deemed “soil banks” — or what’s left of them after erosion takes its toll — and simply return them to the canal.

It’s a six-month process, but he says it improves water quality, reintroduces freshwater, and allows a wetland ecosystem to take root. Grasses and herbaceous plants, like irises and some species of hibiscus, begin to flourish while crustaceans, redfish and speckled drum make a home.

The Tribes aren’t the only ones doing this. A federally funded project began this year at Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, just outside of New Orleans, to backfill canals within the park.

Turner has followed 33 instances of backfilling canals since the 1980s, and in those canals that never reopened, “the soil bank gets colonized immediately, within one to two years, by wetlands again.”

Would this work on a broader scale? Instead of considering this option, the only alternatives listed for the sediment-diversion project are to either regulate the diversion so less water and sediment flow through — or do nothing.

Nature Plus Manpower

Lopez sits up in his chair, his voice becoming serious as he says, there’s no “silver bullet” to fix Louisiana’s coastal land-loss problem.

“You need an array of different projects,” he says.

Though backfilling canals would ultimately cost less than the $1.4 billion project — about $12,000 per canal — the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion would make a bigger difference. By using the natural energy and potential of the river to deliver sediment, the state can avoid the use of fossil fuels to move the precious soils. Lopez says this is more cost- and climate-efficient.

But nature can only undo so much damage on its own. Restoring wetlands, he says, will still require some manpower.

“The river only has so much reach when you divert the sediment and can only deliver it so far,” Lopez says. “For areas that are critical to rebuild, where it’s beyond the reach of the river, you go into your toolbox to mechanically rebuild those wetlands. Use a river where you can, and if you can’t, go to Plan B: dredging.”

The project has elements of both. The plan calls for crews to dredge areas farther from the diversion but still in proximity of the project, as well as when necessary for conveyance channels.

The Risks of Action

Although the biggest threat to the region comes from inaction, moving forward also has potential for pain. One risk from this massive river diversion project could come from the smallest organisms that live in the water.

Turner, who describes himself as an “activist scientist,” recently tracked data from a smaller-scale diversion.

“We track the nutrients going in and out of it and also what happens downstream,” he says.

In this case, the diversion created a new problem. The increased nutrient content caused algal blooms and eutrophication, or excessive nutrients that help plants flourish to the point where the animals living in the water suffocate. The pond in the small-scale diversion — the entire scope of the project — turned deep green and dead fish floated to the surface.

Turner fears a diversion as big as the one proposed for Barataria Bay could result in a continuous algal bloom that would choke out animal life from thriving in the wetlands.

Many people in Louisiana depend on that wetland diversity. The state is known for its seafood industry: Its healthy swamps allow crabs, shrimp, oyster, alligators, crawfish, and various species of fish to prosper.

“No wetlands, no shrimp,” Turner says. The point of the project is, in fact, to build wetlands.

The diversion would also freshen up the estuary water, eventually creating an ideally perfect home for meandering crustaceans and gleaming fish. But Philippe worries that the change would be detrimental to those who make a living in Barataria Basin.

“The project would put more freshwater into the bayous, causing saltwater species to migrate,” she says. “Local traditional fishermen would have to incur added expense during harvest season.”

Alongside traditional anglers, hundreds of commercial seafood fishermen, some third- or fourth-generation, live season to season, relying on the profit from each harvest to feed their families. The project would gamble their livelihoods. What if it doesn’t work?

The industry contributes around $2.4 billion annually to the state’s economy, so the state would likely suffer a deficit.

Other marine life could also deteriorate. The now-salty marshes of Barataria Bay are home to more than 1,000 bottlenose dolphins. Biologists warn that the introduction of freshwater through the diversion project could kill off hundreds of the marine mammals.

View this post on Instagram

In consideration of these concerns, the plan includes wildlife protection efforts and roughly $300 million in mitigation costs to the commercial fishing industry.

Lopez acknowledges the risk coastal commercial fishermen face but says some can put the potential suffering aside in hopes of a brighter future.

“They realize this hurts them in the short run, but they care about their great-grandkids, their families,” Lopez says. “But it’s hard, and it’s unfair to expect someone to make that kind of tradeoff.”

A Diversion Track Record

There’s no chance the project would not work, counters Lopez.

“Zero,” he laughs, folding his fingers into an egg for the camera. “You can’t stop a diversion from building land,” he adds.

Here’s a close-up of the West Bay Mississippi River Diversion- from Sentinel Image I posted yesterday. This diversion was opened in 2002, augmented with artificial islands from about 2009-2015. The islands developing tails, are is partial conformation to the river’s flow. pic.twitter.com/i9ILlxAAUW

— Alex Kolker (@AlexSKolker) March 4, 2021

Previous, smaller diversion projects point to the potential for success. A 2012 study on the impacts of salinity from previous Mississippi River diversions found the levels varied, depending on the season and weather. The shift in salinity had different effects on different species, with some animals and plants better tolerating the salt-water.

The Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion Project, for example, began operating in 1991 after three years of construction. During its 11 years of operation, alligators creeped back to claim the terrain, waterfowl flocked to nest, and oysters thrived with lower mortality rates.

There are, however, examples of species that have not that good luck: Blue crabs and brown shrimp appeared to be less abundant after the diversion.

Overall, though, Lopez says, “diversions are the core processes that fundamentally make our estuary as productive as it is.”

Time for Action

Scientists and activists say without progressive restoration, the Gulf of Mexico shoreline will lap along the edges of New Orleans within 100 years. The Atakapa-Ishak/Chawasha will be forced to relocate, leaving parts of their history and heritage to the water. Louisiana would not only lose the Mississippi River Delta, but the river channel as well. The state would lose the port of New Orleans, threatening the city’s economy.

View this post on Instagram

The fate of what happens over the next century may depend on what happens over the next several weeks.

This September the Army Corps of Engineers expects to make public the diversion project’s final Environmental Impact Statement. After that, the public will have the opportunity to submit comments. The Corps will then determine whether the project meets the requirements of the Clean Water Act, the Rivers and Harbors Act, and other regulations.

All of this will move quickly. The Corps plans to issue its Record of Decision in December, and if it approves the project the Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority can start scheduling operations. Construction could begin within two years.

Meanwhile, Philippe, Lopez and Turner race to have their voices heard — all to bring back some of the million lost acres.

![]()

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Previously in The Revelator:

Set It Back: Moving Levees to Benefit Rivers, Wildlife and Communities