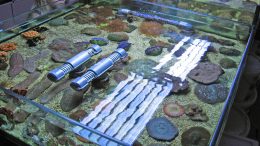

On any given day, in shops around the world and online, customers can pay as little as a few dozen dollars to buy living corals for their aquariums. While some of these coveted, brightly colored pieces of coral are sourced from farms, others come directly from ecosystems that are dying, such as Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Reefs have endured intolerable conditions for decades now due to global warming. Since February 2023 over three-quarters of the world’s coral reefs have endured heat stress in an ongoing global mass bleaching event, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration told Reuters last October. Scientists from NOAA and the International Coral Reef Initiative declare these events when significant bleaching happens in all ocean basins where warm-water corals can be found. The current global mass bleaching event is the largest one on record.

“Every place I know is dying at different paces,” says Tom Goreau, president of the nonprofit Global Coral Reef Alliance. “We’re looking at the last survivors almost everywhere.”

Yet the commercial trade in live corals from the Great Barrier Reef continues — as it does from other reefs around the world — and in fact has increased dramatically over the past 20 years.

Remarkably, trade endures even during catastrophic bleaching events. The Great Barrier Reef suffered its worst bleaching event on record in 2024 as temperatures in the Coral Sea hit a 400-year high. Despite this historic event Fisheries Queensland — the agency that manages fishing activities there — neither temporarily closed its commercial coral fishery nor imposed emergency restrictions on extraction.

For Goreau the continued trade in corals at this juncture begs a question: “Should we be exploiting an ecosystem that’s going extinct in front of our eyes?”

Trade is not Goreau’s area of focus, but identifying and tackling threats to reefs certainly is. In the 1980s he developed the method for using satellite sea surface temperature data to predict coral bleaching. Goreau is also the co-creator of BioRock, a technology that facilitates the recovery of marine ecosystems like reefs.

Goreau acknowledges that global warming overwhelmingly poses the biggest threat to reefs. While he describes trade as a “small part of the problem,” he opposes commercial exploitation of corals at this critical time because these ecosystems are already so dangerously at risk.

Countries “shouldn’t be exporting corals in this day and age,” he insists.

A Presumption of Innocence, a Wide-Ranging Trade

Queensland, on the other hand, has long considered the coral trade to pose little threat to the Great Barrier Reef. The state’s coral fishery — the area where it permits corals and similar organisms like sea anemones to be fished — has operated under the principle that “impacts of harvesting are likely to be low,” as explained in a 2021 assessment of the fishery by Australia’s federal government.

Authorities have considered the exploitation to be low risk because fishers selectively target corals guaranteed to sell in the aquarium trade and extract them by hand, rather than using broader or more destructive methods that risk harming other marine species, among other reasons.

Marine conservation ecologist Morgan Pratchett has conducted extensive research into Queensland’s fishery. As he put it to me last year, the state government has “assumed” coral extraction on the Great Barrier Reef to be sustainable. However, with reefs at risk from escalating threats like climate-induced bleaching, he said the trade in corals from Australia and elsewhere is being subject to increased scrutiny and restrictions.

View this post on Instagram

Some global bodies have recognized the trade as a threat to reefs for decades. Notably, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora has restricted commerce in stony corals, meaning corals with a skeleton, since 1990.

This treaty body regulates global trade in wild species where commerce itself is among the risks to their conservation. It lists species depending on their risk of extinction and the trade rules vary accordingly.

In the case of stony corals, CITES regulation does not forbid commercial trade but makes it subject to conditions such as permit requirements.

But even with that modicum of control, the global trade in corals has grown substantially in the past few decades, with Indonesia and Australia currently topping the list of exporters. “Harvesting” of corals in the Queensland Coral Fishery has increased by around 700% since 2006, reaching over 620,000 pieces in 2021. Meanwhile Indonesia permitted the harvesting of more than 411,000 live corals in 2021. Fisheries commonly target stony corals to supply the aquarium trade. But other reef materials like coral rock with soft corals or other live organisms attached are also traded.

In some countries corals are also targeted for the curio and jewelry trades. Some but not all of this trade is regulated by CITES. NOAA warns that the exploitation of Corallium corals — typically for jewelry — is often unsustainable and media reports show there is extensive illegality associated with it.

Some harvested corals don’t go to the end-consumer: They end up in coral aquaculture, which grows and breeds coral that will then end up on the market. Experts generally view this as a more sustainable form of exploitation. Around half of Indonesia’s exports originate from coral farms, according to its 2023 sustainability assessment of the trade, whereas Australia largely exports wild-sourced corals.

Altogether, this high level of exploitation makes corals the most traded marine animals covered by CITES.

A Flaw in the System

Countries that are party to the international treaty meet every two to three years to consider at-risk species for new or additional protection, with interim meetings of its specialist committees happening in between. The process for listing and uplisting species in CITES’ Appendices is notoriously slow. This means the treaty often fails to adequately restrict trade in species prior to them becoming threatened.

There are exceptions to this. For instance, CITES has listed entire groups of species in the treaty at their taxonomic level — i.e., genus, family or above. These listings typically occur to safeguard groups that are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation or to protect at-risk species within “lookalike” groups, meaning species that are hard to distinguish from each other. This is how all stony corals came to be regulated by CITES, including species not yet officially recognized as threatened.

However, species like stony corals — which face sudden, sharp catastrophic events that ultimately contribute to their longer term declines — highlight a particular flaw in the CITES system: It does not have an “emergency brake” mechanism that could quickly prohibit trade entirely when a species faces an abrupt crisis, as has happened with corals in the past two years.

Conservation biologist Alice Hughes points out that individual countries can list species in CITES’ Appendix III — which requires permits for all trade — on an intersessional basis, meaning that this appendix offers a quicker route to trade prohibitions than typically happens within CITES. However, Appendix III is country-specific, so parties are able only to list and prohibit trade in their national populations of a species; populations from outside those countries remain unprotected unless they have their own listing.

But Hughes says this appendix is rarely applied as an emergency brake to safeguard species facing climate disasters, disease, or other crisis situations. Rather, countries tend to use Appendix III for listing endemic species where trade itself poses the risk.

That means CITES still lacks adequate mechanisms to prohibit trade in species that are hit by sudden crises. Instead, countries decide — slowly — whether to make changes in these circumstances. In some cases, that can take years.

Many experts worry that coral reefs don’t have that kind of time.

Managing the Coral Trade: Each Country Is on Its Own

On the national level, neither Indonesia nor Queensland mandates closure of its coral fisheries during bleaching events, according to email responses provided by Queensland’s Department of Primary Industries and Indonesia’s Director General of Marine Spatial Management Victor Gustaaf Manoppo.

Fisheries Queensland and Manoppo’s Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries respond to bleaching in other ways, such as working with varied stakeholders to monitor, evaluate, and disseminate information on bleaching. Both departments say these findings inform long-term plans for reef management.

Additionally, the jurisdictions have management frameworks in place that protect certain corals from exploitation during bleaching events.

Manoppo tells me by email that fishing is prohibited in the core zones of Indonesia’s Marine Protected Areas. These areas are safeguarded for their “ecological value including resilience to climate change,” he explains, which means reefs here are “expected to have a higher chance of survival” in the event of bleaching. In other zones, Manoppo says, utilization is permitted but controlled, such as through restrictions on the scale of activities and fishing gear types.

The Indonesian government also sets a quota for the harvest of different genera or species in each province where extraction is permitted, according to its sustainability assessment.

Meanwhile coral extraction is prohibited in around 38% of Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. In emailed statements, DPI points out that harvesting is permitted only under license, with species-based catch limits in place that “ensure biomass levels are maintained at 60% for key stocks.” DPI insists that its management approach is “highly precautionary” and ensures targeted corals are resilient to pressures like fishing and bleaching.

Queensland has also worked with industry over the years to develop response plans for events like bleaching, which include a provision for emergency closures of fisheries. I asked DPI whether this provision has ever been utilized. I received no response.

The plans also contain voluntary recommendations for fishers, such as instructions to avoid targeting stressed corals, although this guidance is not subscribed to by all industry members, according to Australia’s federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

Nonetheless, in its emailed statements DPI says coral fishing “does not occur in areas impacted by climate events” because “impacted and unhealthy corals are not commercially desirable or viable to harvest.”

Troubling Findings

Despite the coral trade being subject to management and CITES oversight, Hughes argues that “with bleaching and acidification posing major risks to corals, stacking more risk from harvest seems unnecessary and irresponsible.”

She adds, “Even if the fisheries are purported to be precautionary, that does not mean they properly account for all risks.”

Accounting for all risks is impossible because there are many unknowns in the trade, according to Pratchett. He told me we lack robust information about the populations of targeted species, the level of exploitation they face, and how vulnerable they are to other stressors.

To address some of these information gaps, Australia’s climate and environment department commissioned Pratchett to carry out surveys of nine heavily targeted coral species — “key stocks” in the Queensland fishery — in 2023-24. This authority decides whether Queensland is permitted to export corals.

The department disclosed some of Pratchett’s findings in an assessment of the QCF in October. He found a “significant difference” in the abundance and biomass of several species in fished areas compared to unfished areas. In some fished areas, certain species had biomasses less than 60% of those in unexploited areas, while other species had similarly lower abundances than their counterparts in unfished areas.

Pratchett also found reductions in average sizes and color varieties in fished areas, presumably because fishers extract the bigger, more colorful corals.

Although the environment department acknowledged that the surveys pointed to “significant localized depletion” for some species, it approved coral exports for another three years in its assessment. The approval came with conditions, including a requirement that Queensland review information on coral species at risk from the fishery and change catch limits where necessary by August 2025.

The department also instructed the state to develop and implement a “Severe Event Response Plan” to formally guide fishery management in the event of emergencies like bleaching by October 2026. A spokesperson confirmed by email that Queensland is required to “adaptively manage” the fishery in the interim, too.

Asked about its plans for adaptive management, DPI sent this unattributed statement: “Fisheries Queensland will continue working in collaboration with key stakeholders during all future events in support of responsive, adaptive management, with a significant amount of work already underway and planned for responding to severe weather and disturbance events.”

Cascading Impacts

Countries like Belize and Thailand err on the side of caution by prohibiting commercial exports of live corals. However, the legal trade provides cover for illegal exploitation of reefs. This criminality blights several countries, including those that have banned trade in their corals.

Considering Pratchett’s findings, prohibiting exports seems a wise choice because the impacts he uncovered, such as lower abundances and reduced sizes of heavily targeted species, have implications for reef ecosystems.

For one thing, Goreau explains, corals’ reproductive capacity is “determined by size and not by age.” This means reduced coral sizes risks impacting spawning because “if corals are too small, they’re not reproducing,” he says.

Studies show that bleaching itself is reducing some corals’ reproductive output, including Acropora species that are popular in aquariums. Most traded corals belong to this genus, which Goreau points out is a group that is “super sensitive” to bleaching.

Simply put, trade reduces the abundance of some species at the very moment they need as many survivors around as possible for reproduction and recovery.

In turn, diminished populations of Acropora species risks inhibiting recovery of wider reef communities after bleaching because they are ecological engineers. Goreau describes Acropora as “the best corals of all.” As fast-growing, branching, reef-building corals, he says they provide high surface cover and dissipate waves that risk breaking other corals, while also providing the optimal habitat for fish.

Considering factors like this, trade seems to be an important block in the teetering Jenga tower of corals’ future survival.

Business As Usual

While the coral trade offers a stark example of how wild organisms continue to be exploited while on the brink of disaster, there are many others.

Over 40% of amphibian species are globally threatened due to issues like habitat destruction, disease, and climate change. Yet a huge trade in these animals endures because, for example, some species’ legs are considered a delicacy or people want to keep them as pets. Regulation of this trade is limited, and few amphibians are listed in CITES. The treaty body is presently determining whether to regulate trade in other amphibian species in a process that takes years.

Hughes points to Asian songbirds as another example. They’re in crisis, threatened by both a loss of their homes and the wildlife trade. Even with trade as a known primary threat for this group, conservationists face a lengthy battle convincing CITES to regulate their trade, Hughes says. She explains that each species will have to assessed and listed separately, which is extremely challenging as countries do not collect robust data on the populations and exploitation levels of most wild species.

Hughes says CITES could take practical steps to protect species in crisis, such as working to better enable swift decisions on regulating trade in those species. But on a more fundamental level, Hughes believes a paradigm shift is necessary.

“We need to reconsider how we view wild species,” she argues, highlighting that they are often seen as commodities above all else.

For Goreau, the commodification of coral reefs and their inhabitants right up to the ecosystems’ bitter end is regrettable but not surprising.

“There are many factors killing reefs,” he says, and the determination of countries — particularly rich ones — to maintain business as usual for trade in nature’s “goods” is at the core of every reason he mentions, be it dredging, agricultural pollution, or fossil fuel production.

“We have pushed reefs past their capability for surviving,” he warns. “They really can’t take very much more.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Saving Living Jewels: One Woman’s Mission to Shine a Light on the Ornamental Fish Trade