Can saving an endangered fish help heal some of California’s regional water woes?

Masses of steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) once migrated freely between the sea and river headwaters along the California coast. That began to change about a century ago as dams, stream realignments, bridges, invasive species and degraded estuaries all took their toll on steelhead, putting this intriguing member of the salmon family on a path toward near-extinction. Now a coalition of private and public entities hopes to reverse the trend — and re-invigorate vital watersheds in California’s most densely populated region in the process.

“It’s not just about water for fish,” says Sandra Jacobson, South Coast director for California Trout, Inc., a state conservation group also known as CalTrout. “Native fish are one of the best indicators of the health of a watershed. If human-caused factors are affecting the fish, it’s only a matter of time before our bays, beaches, recreational venues and even our drinking water are affected.”

The nonprofit spearheads the South Coast Steelhead Coalition, which aims to protect and restore steelhead populations along coastal waters in San Diego and Orange counties.

Steelhead, like salmon, return to the headwaters where they were born to spawn. However, unlike salmon, which die after depositing their eggs, a steelhead can survive to restart the cycle, spawning three or four times in its lifetime. These anadromous (oceangoing) fish can also thrive in fresh water, where they are known as rainbow trout. This and their ability to adapt to drought and flood cycles gives them the best chance of survival in California, where flashy watersheds are the norm, Jasobson says. Steeply sloped catchments such as high mountains channel massive amounts of rainwater into a streambed, producing flash floods and creating a temporary superhighway for anadromous fish.

“The steelhead like these flashy systems,” says Jacobson.

Steelhead populations dropped so precipitously that the species was listed as endangered in 1997. They’re still very much at risk; in the case of the Southern California coast steelhead, just 500 adult fish currently reach their spawning grounds. And they aren’t alone in their decline. A report released in 2017 by CalTrout and the University of California, Davis, found that if current trends continue, 74 percent of California’s 32 salmonid species will likely go extinct within the next 100 years.

The South Coast Steelhead Coalition hopes to reverse the trend and create conditions for steelhead to once again thrive. Recovery efforts include reworking waterways under bridges and dynamiting dams to restore the steelhead’s aquatic pathways up into their home watersheds. The project also works to remove non-native aquatic species like bass and sunfish, which compete for food and even eat steelhead eggs, further depleting the population. The project also actively protects native trout by improving habitats through removing excessive vegetation in streambeds, modifying smaller fish passages for increased access, and on rare occasions rescuing trout during extended drought conditions. These steps were included in a plan developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2012 to bring steelhead back from the brink.

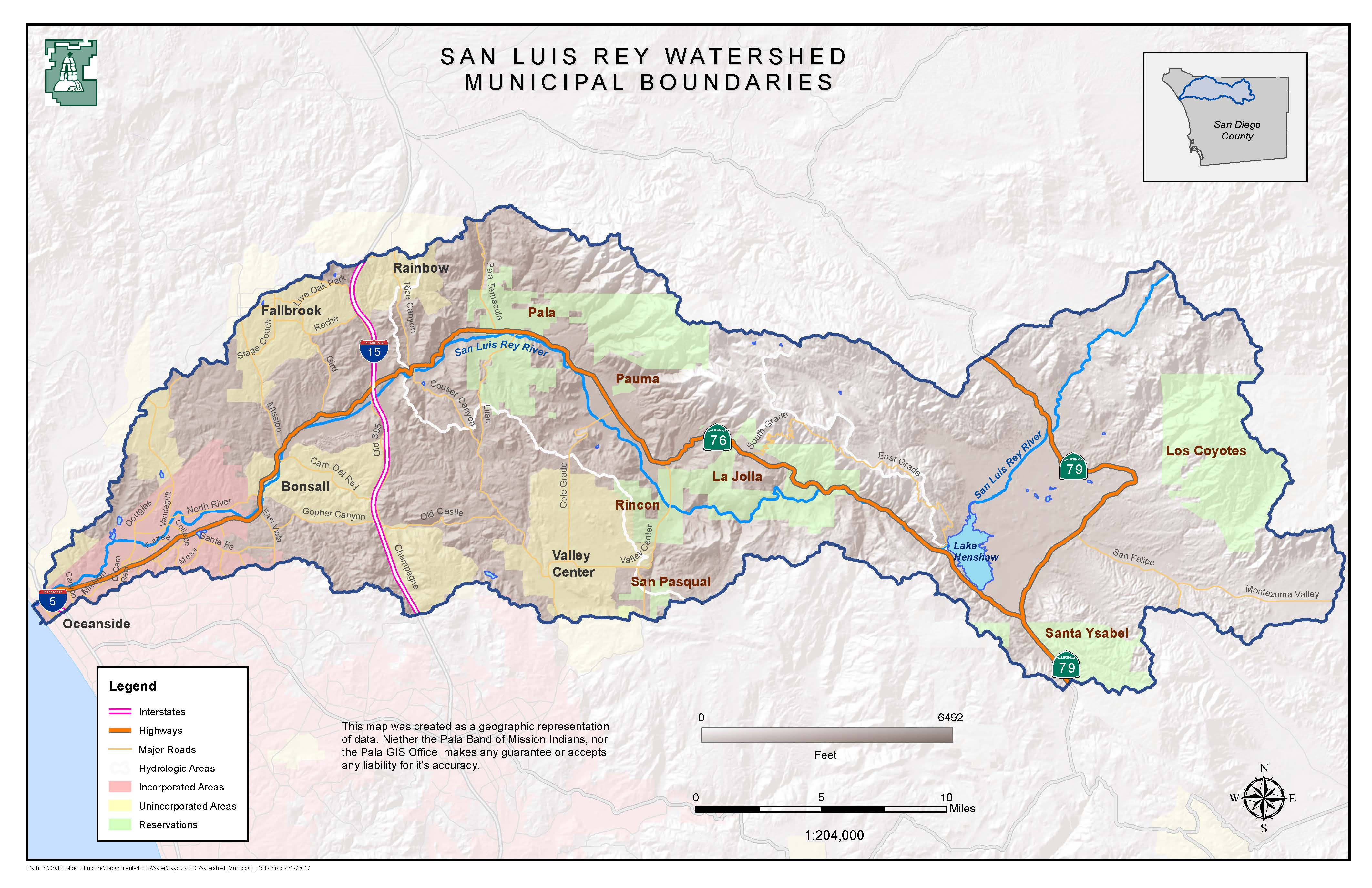

In Pauma Valley, where the San Luis Rey River meanders through north San Diego County to rendezvous with the Pacific, the steelhead coalition concentrates on improving water quality, increasing both groundwater and surface-water flows, and removing the species’ biggest migratory barrier: the waterway underneath the Pauma Creek bridge on State Route 76. The most robust steelhead population lives in the headwaters of Pauma Creek as rainbow trout, and Jacobson says improved water quality and reworking the waterway under the bridge will support this population’s ability to migrate to the ocean and undergo smoltification, the process of transforming into their saltwater-adapted steelhead form.

The project also will help provide a sustainable water supply for residents in this heavily agricultural valley. Initiatives in the works include installing a weather station and soil sensors on the Pala Band of Mission Indians’ lands, where rains smack into the 6,100-foot-high western slopes of Palomar Mountain and plunge down Pauma Creek to join the San Luis Rey. Heidi Brow, a water resource specialist with the Pala Band, says farmers and residents can access information from the reporting stations to inform irrigation decisions and conserve water. The Pala Band also participates in rainwater-catchment and graywater-reuse programs, further conserving water and reducing groundwater pumping.

The stakes are high for people as well as fish. Pala’s wells ran dry in 2017 and the tribe had to purchase water from a local water district. Similarly, the five Pauma Valley tribes in the watershed just wrapped up a 50-year lawsuit to restore their water rights, only to encounter a water shortage this year.

Even as the coalition makes progress, some people aren’t convinced that the steelhead’s migration route can be saved, or that restoring them to their old waterways is cost-effective. “I’d love to have trout swimming all the way up,” says Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians Chairman Bo Mazetti, whose tribe’s land lies along the river. “But realistically, we’ve got climate change and drought occurring and there’s just no way the river is going to run all year anymore. We’re not in the old days any longer.” He’s also worried about the significant resources being spent on the project.

Jacobson disagrees with Mazetti’s first concern. “The trout don’t need water in the river all year long,” she says. The fish only migrate between December and May, when the river flows all the way to the ocean, meaning drought during summer months probably won’t affect them.

However, nobody can dispute the hefty price tag for saving steelhead: Pala’s weather stations were partially funded by a $176,000 grant from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The price tag for just one new fish passage project currently in progress in Ventura County is even larger: it’s expected to reach $60 million by the time it’s completed in 2021.

Nonetheless, experts say restoring the coastal watersheds that the fish depend on will also help refill some of California’s most depleted aquifers, increasing water supplies throughout the drought-parched region. As Jacobson says, “The fixes we’re working on to save the fish will also help to save the rivers.”

Reporting for this article was made possible by an award from the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources and with support from the UCLA Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategy’s Ethnic Media Fellowship Program.

© 2018 Debra Utacia Krol. All rights reserved.