When armed militants with a grudge against the federal government seized the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in rural Oregon back in the winter of 2016, I remember avoiding the news coverage. Part of me wanted to know what was happening, but each report I read — as the occupation stretched from days to weeks and the destruction grew — made me so angry it was hard to keep reading.

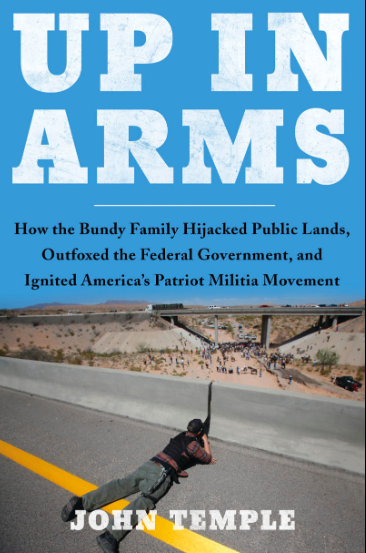

That’s why I picked up John Temple’s new book Up in Arms: How the Bundy Family Hijacked Public Lands, Outfoxed the Federal Government, and Ignited America’s Patriot Militia Movement.

I wanted to see what I’d missed. And I wanted to understand the extremist ideologies that continue to dominate many discussions in the American West.

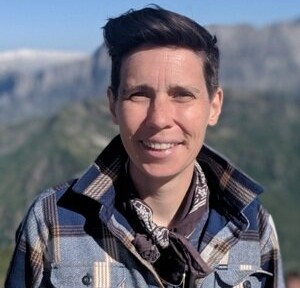

Temple, an author and journalism professor at West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media, provides a page-turning account of both the 2014 standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada, that launched scofflaw rancher Cliven Bundy and his family into the national spotlight and the 2016 occupation of Malheur, led by Bundy’s sons Ammon and Ryan.

Temple, an author and journalism professor at West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media, provides a page-turning account of both the 2014 standoff in Bunkerville, Nevada, that launched scofflaw rancher Cliven Bundy and his family into the national spotlight and the 2016 occupation of Malheur, led by Bundy’s sons Ammon and Ryan.

“It’s obviously an exciting story with cowboys and guns and takeovers and standoffs,” Temple tells me about the book. “But it sheds light on public lands issues, environmental issues, on questions about how the government should handle these situations and the urban-rural divide in this country.”

The book also delves into the history of the Sagebrush Rebellion, a western U.S. movement against federal ownership of public lands that ignited in the late 1970s and has continued to smolder in the decades since.

The Bundys, who still subscribe to this line of thinking, refused to recognize the Bureau of Land Management’s authority over the public land where they graze their cattle (or the federal government in general). That ultimately led — after 20 years of federal agencies looking the other way — to an armed standoff in which the FBI attempted to seize the rancher’s cattle after years of unpaid grazing fees and mounting fines.

Spoiler alert: It didn’t end well for the government.

Temple then chronicles the play’s second act, during which the Bundy sons engineered the takeover of the federally run Malheur National Wildlife Refuge for more than a month. The pretense was defending local Oregon ranchers Dwight and Steven Hammond, who were sentenced to jail for federal land arson, but who actually eschewed the Bundys’ help. The occupation turned out to be more of a publicity stunt than anything — one that ended in spectacular failure (although the Bundys insist it was a success). In the process they also trashed the refuge headquarters and racked up a $9 million tab for taxpayers.

While Up in Arms gives a detailed view of the ideology that motivates the Bundys, the story is much bigger than them. It’s also an exploration of the motivations of some of the most hardline anti-federal militants in the country — not just the Bundys, but the ragbag collection of so-called Patriot movement followers that flocked to their ranch, even when most of them lacked understanding of public-lands issues and the cause they were backing.

In fact, Temple says, he first came to the story of the Bundys researching an unrelated project about militias. As a result there’s not much in the book about the underlying environmental issues at the heart of the Bundy actions, including the impact of renegade ranching on public lands.

But Temple writes about the personal histories of many of the supporters who turned up for the initial showdown in Bunkerville and others who joined the occupation at Malheur. He reveals the power dynamics among different Patriot militia groups as they jockeyed for media attention and acolytes.

While the Bundys honed their talking points in scores of interviews about their anti-government rhetoric and their calling from God to act on it, Temple says that most of the other Bundy supporters didn’t have much political inspiration or well-formed ideologies.

“I think some of these folks were motivated on a very personal level where they have trouble with authority and that kind of thing,” he says. “Every individual seemed to have a different set of grievances or issues that were driving them, but it coalesced around a few things: Distrust of the federal government and the feeling that the federal government was overreaching in its authority, and the Second Amendment.”

What could go wrong?

As Temple writes, a lot went wrong on both sides of the confrontation between the government and the militias. This was on full view when the Bundys and their compatriots eventually faced their day in court.

If you’ve ever wondered, as I did, how the leaders of an armed insurrection that occupied federal property, degraded public lands, and terrorized government workers escaped punishment, it’s explained here in great detail. Temple writes about not just the court proceedings that followed the standoffs but the main players on the federal government’s team, including FBI leadership involved in Bunkerville. A series of bumbles and missteps ultimately led to the prosecution’s ultimate failure.

There’s no happy ending, unless you believe divine providence is shining down on the Bundy clan. But Temple’s book paints a useful picture of the simmering, ongoing range war in the West and the havoc an unlikely alliance of right-wing groups can wreak when they converge.

That’s the most sobering part of the book: It’s likely a preview of things to come.

![]()