Could deep-sea exploration give way to deep-sea mining?

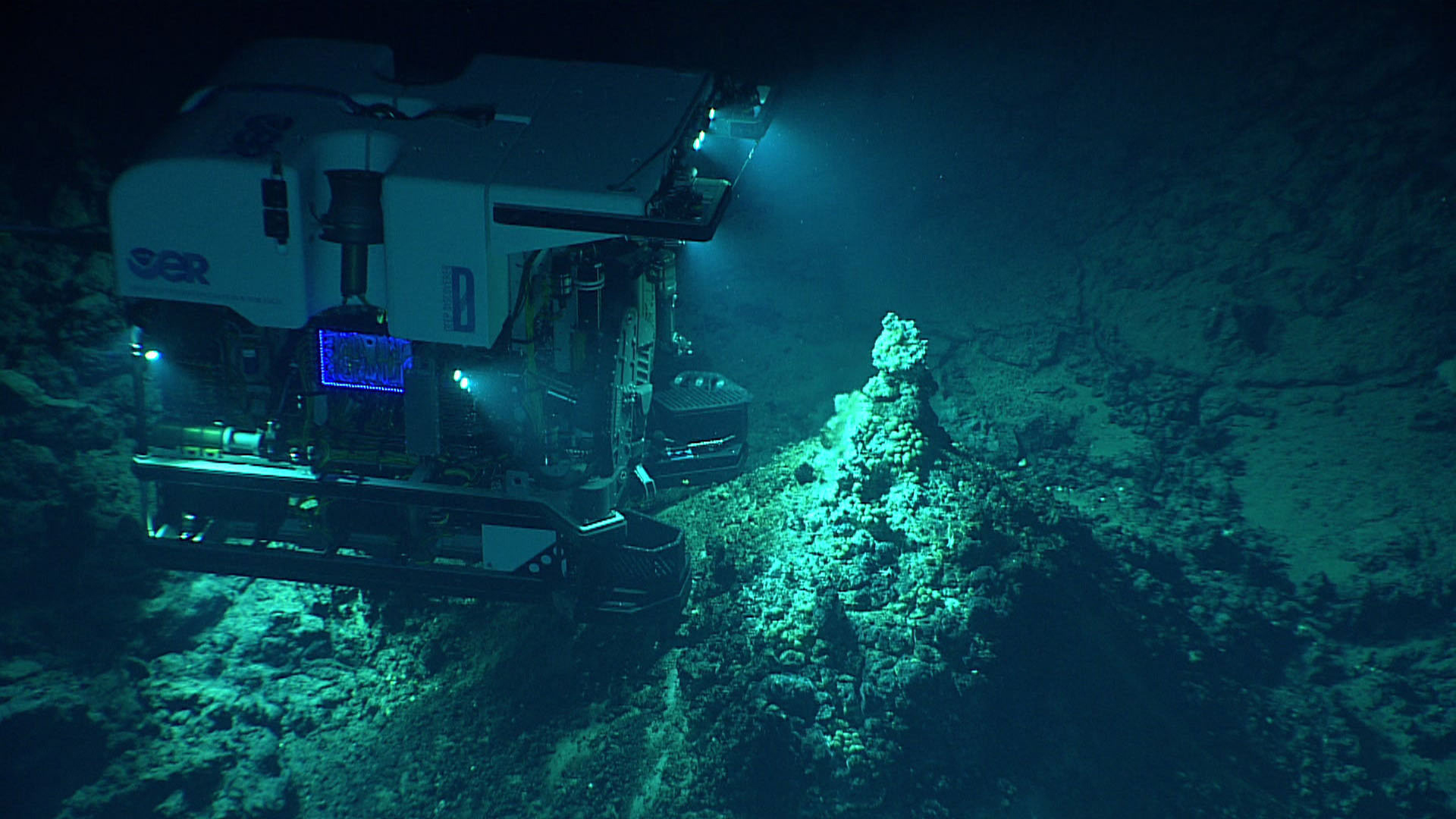

For the past two years the Okeanos Explorer, an exploration vessel operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization, has been crisscrossing the Pacific Ocean, diving in U.S. marine protected areas to improve our understanding of the 95 percent of deep ocean that remains unexplored. The ship transmits live video feed from hi-def cameras on its two remotely operated vehicles — “ROVs” — to scientists both onboard and onshore (and members of the public like you and me, with internet connections).

The chosen dive locations for the three-year CAPSTONE (Campaign to Address Pacific monument Science, Technology, and Ocean Needs) expedition — seamounts, trenches and ridges — are hotbeds of life. The ROVs find “new” species all the time.

The dives also document what would be destroyed by mining.

You see, these locations contain deposits of manganese and rare earth elements, valued for use in computers, cellphone and rechargeable batteries for electric and hybrid cars. The technology to exploit the minerals has been elusive, but the likelihood that these places will be mined continues to hover on the horizon.

According to Professor Cindy Lee Van Dover, a marine scientist at Duke University, there’s a lot of activity in the maritime sector related to building technologies — though she doesn’t think any active commercial mining is yet taking place on the seabed. She did point out that two mining licenses for exploitation (a step beyond exploration) have been issued for deep-sea work in Papua New Guinea and Saudi Arabia.

Deep-sea mining involves three materials: polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese (Fe-Mn) crusts. The first, better known as manganese nodules, and the second, found around hydrothermal vents, are likely to be developed first, according to Dr. Christopher Kelley, science advisor to CAPSTONE.

The third — perhaps the most interesting and environmentally sensitive — won’t be far behind. Ferromanganese crusts are laid down on the flanks of seamounts by minerals precipitating out of seawater at 1 to 5 millimeters per million years. Seamounts are often inhabited by animals that grow extremely slowly and have low reproductive rates.

Such habitats don’t rebound quickly after intervention. Mining these deposits, which are up to three times richer than deposits on land, involves stripping the crust off the hard substrate and getting the lode to the surface — an invasive and difficult process. China currently controls most terrestrial rare-earth element production, so other countries see the potential for big profits beneath the sea even with technological difficulties to overcome.

Why is this important to know? Well, countries have control over resources in their Exclusive Economic Zones, so the United States can extend leases to mine in the Marianas, which are a U.S. territory. The International Seabed Authority controls mining in the “Area,” which is what it calls the 64 percent outside national jurisdiction. The United States has not ratified the Law of the Sea and so is not a party to the authority — yet it does attempt to abide by its stated commitment to minimize harmful effects of deep-sea mining. Okeanos Explorer, according to its website, provides crucial baseline information “to gain a better understanding of the communities that are at risk and put measures in place to mitigate the impacts of mining and help preserve these unique communities.”

I have followed the ship’s expeditions since I stumbled on its web link last summer, which offers a much closer view of corals, sponges and sea cucumbers than I have ever seen SCUBA diving. During broadcasts the scientists discuss previously undiscovered gorgeous and unusual life forms; they even redefine species parameters in real time, by phone link and in a chat room. Before the voyages of the Okeanos and other exploratory vessels, the bottom of the deep ocean was believed to be fairly barren — but as it turns out, it teems with animal life (no plants though; they need sunlight to live). Bright white LEDs on Deep Discoverer, the main ROV, uncover vibrant colors that seem out of place in this sightless, lightless world.

What’s the future of these missions? In early March of this year, under the new, anti-science Donald Trump administration, NOAA seemed poised to lose 17 percent of its budget. Fortunately a May 1 congressional compromise to keep government functioning through September spared the Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, which contains the office that operates Okeanos Explorer. The agency has declined to elaborate on how future funding prospects may fare, although its own 2018 budget request cuts $12.5 million from its ocean exploration program. Meanwhile, Trump’s proposed “Taxpayer First” budget, announced last week, also contains a broad 15.8 percent cut to the Department of Commerce, under which NOAA operates.

Beyond the budget itself, Trump last month ordered a review of drilling rules instituted after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, a move that, according to the “Presidential Executive Order Implementing an America-First Offshore Energy Strategy,” will encourage energy exploration and production. The order also states “The Secretary of Commerce shall, unless expressly required otherwise, refrain from designating or expanding any National Marine Sanctuary under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act…unless the sanctuary designation or expansion proposal includes a timely, full accounting from the Department of the Interior of any energy or mineral resource potential within the designated area” (emphasis added).

On April 26 Trump ordered Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to reconsider the status of recent national monuments. Four of them are areas under exploration by the Okeanos, including the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument. This comes after NOAA’s March 13 decision to add the monument to the national inventory list for possible change to marine sanctuary status. Marine national monuments and marine sanctuaries offer similar protections, but monuments are established by presidential proclamation and sanctuaries by the marine agency, with extensive public input.

In July 2015 scientists from the United States and New Zealand wrote a report, published in the journal Science, favoring the use of networks of marine protected areas to “reduce uncertainty about future mining activities and protect existing mining claims and economic investments, all while safeguarding deep-sea biodiversity and ecosystem function at relevant geographic scales.” The report came out in advance of an international meeting that formulated a draft code for regulating mineral exploitation in international waters. Similar mining-test activities are ongoing on national seabeds, yielding vital data for conservationists: By illuminating the Pacific areas protected by the United States, the Okeanos makes us acutely aware of what could be destroyed by a political push to dig up these minerals.

The original work for the report was done in 2007-2008 but Jack Kittinger, coauthor and senior director at Conservation International Center for Oceans, stands by the research conclusions. While he feels that a number of issues could affect how soon mining becomes economically viable, whether of manganese nodules or ferromanganese crust, “implementation of marine protected areas and protection of seamounts should be done regardless of what’s going to happen with deep-sea mining,” he says. “It’s good precautionary principles. It’s good PR.”

Budget cuts could still affect the Okeanos, but certainly won’t doom deep-sea mining. Yet if the planning process incorporates preservation, it’s possible to avoid the scenario — with Trump’s emphasis on promoting business and rolling back regulations — that the government will grant deep-ocean leases and a new section of the Earth will be pillaged without effective oversight or sufficient public understanding.

Copyright © 2017 Ann Hoffner. All rights reserved.

As we used to say in Earth First!, no compromise! Hands off the deep sea floor. There is no mitigation, oversight, or anything else that will substantially help if humans are allowed to destroy yet another portion of our planet.

Agreed, Jeff. The question is, if those who want to exploit can find a way to do so, are we willing to fight to fund exploration for knowledge and preservation?