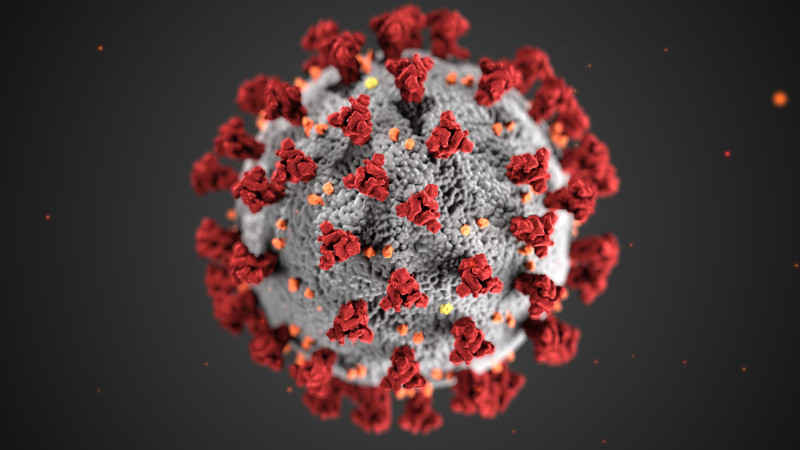

The rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19 made it clear: Emerging infectious diseases present global health and security threats to every home and family.

Like SARS-CoV-2, most new infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, meaning they originate from other animals — and particularly from wildlife. The accelerating frequency and extent to which humans and domestic animals come into contact with wildlife due to land-use change and wildlife markets and trade, together with the lack of proper livestock biosecurity, have increased novel pathogen evolution and spillover.

Combined with ever-increasing global interconnectedness, these trends mean that future outbreaks will occur more often, and spread faster, if we don’t immediately eliminate the primary drivers. We have commonly understood “best practices” to avoid catching Covid-19 from our friends, coworkers, and neighbors: Vaccinate, wear a mask, and socially distance. We now need best practices to prevent pandemic spillover at the source.

1. Protect Habitat

Research shows that landscapes of high ecological integrity (those that are less disturbed and with full ecological function) are resilient in limiting spillover and spillback between humans and animals of the pathogens innocuously circulating and evolving among wildlife. Those un-degraded environments — areas with limited human penetration, encroachment and exploitation — maintain a wealth of proven complementary and cumulative natural barriers to the spread of pathogens with pandemic potential.

Sadly, however, human activities and exploitation now continuously erode and destroy these vital barriers. Twenty-five months into the present pandemic, we know we must put an end to deforestation and widespread agricultural conversion and land-use changes. These actions directly disrupt species composition, density and distribution, which in turn drives stressed species into new habitats with newly established behaviors and the potential for increased pathogen shedding.

2. Shut Down the Markets

We must also close markets in large urban centers that sell live wildlife for human consumption — a niche consumer extravagance that mixes a stupendous variety of live wildlife species from diverse sources, both legal and illegal. Animals are either trapped in the wild, come from unregulated captive wildlife farms, or emerge from a porous mixture of both.

The animals are also obtained locally, regionally and — for some species — internationally, then transported under horrendous conditions to market. There live animals are stacked on top of, or next to, each other and intermix with domestic livestock like pigs and chickens — and, of course, people. This allows for direct exchange and recombination of pathogens through respiration, excrement and blood.

The trade in live wildlife patently violates wildlife-human-wildlife interface integrity and increases spillover and spillback opportunities between wildlife, livestock, poultry and ultimately humans. We can no longer tolerate these vast open-access, wholly unregulated, unsupervised market-based experiments in urban agglomerations and megapolises.

Let me be clear: Commercial urban wildlife markets primarily provide luxury products, do not contribute to nutritional needs, and are of negligible economic importance compared with the global economic devastation of a pandemic such as Covid-19.

3. Address Inequality

Beyond the health threat they pose, the live-animal trade perpetuates global inequities. By emptying forests and landscapes, it deprives vulnerable Indigenous peoples and local communities of their rights, food security and cultural needs. Eliminating the urban commercial trade in wildlife will directly benefit these communities, which are critically dependent on accessing food from intact, biodiverse and healthy landscapes.

It would also bolster the global economy. The costs of many individual recent major outbreaks such as SARS, MERS and Ebola are estimated in the tens of billions of U.S. dollars. When all is tallied, the economic devastation caused by Covid-19 will certainly be orders of magnitude greater: in the tens of trillions.

4. Plan Ahead

As governments and the global public health community ponder post-spillover pandemic preparedness, we must strongly advocate for prevention at the source — in other words, for stopping outbreaks where they’d start. Only prevention directly addresses the growing interfaces and barrier losses where spillovers — and more recently spillbacks — into wildlife occur can mitigate future zoonotic disease threats in an expedient, cost-effective manner.

Prevention has been largely missing in the global debates and approaches to future pandemics as the world attempts to learn from Covid-19. So far most conversations have focused on post-spillover preparedness, interventions and health system strengthening. While these steps are critical, they’re insufficient to protect against the coming pandemics.

Some steps have been taken in this direction, though. In the United States, the House of Representatives passed pandemic prevention provisions as part of the America COMPETES Act on Feb. 4. The bill calls on the U.S. government to work with countries to end the commercial live wildlife trade for human consumption. An alternate version of the bill passed the Senate on March 28, so the two chambers must reconcile their differences before it can go to President Biden’s desk. The key primary spillover prevention and One Health policies must be retained during the conference negotiations.

On a global scale, pandemic preparedness — and to a far lesser degree, prevention — has also been discussed in major multilateral forums, including the G7, G20 and the United Nations security council. Most importantly, the World Health Assembly, the decision-making body of the World Health Organization, initiated a global process in December 2021 to draft and negotiate a convention, agreement or other international instruments under the WHO constitution to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

This was an essential step as it recognized the importance of pandemic prevention, which had previously been absent from the global agenda. However, a recent statement by World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in support of a global treaty on pandemic prevention omitted any mention of a prevention-at-the-source approach. This demonstrates that the concept of pandemic prevention has yet to be fully embraced. NGOs and civil society need to urgently inform and nudge governments and delegates at the World Health Assembly to focus efforts on pandemic prevention. At the same time, concerned citizens can engage their representatives to advocate and support funding for prevention.

This pandemic has made it blatantly clear that we can no longer view our health in isolation. We need to implement a One Health framework that recognizes the interrelatedness and interdependencies of all living things and acknowledge health as a tightly intertwined global common.

We know the best practices to avoid the next pandemic. Recognizing and valuing the foundational importance of intact and resilient environments, stopping deforestation, limiting land-use change, and eliminating the commercial live animal trade for consumption will be critical to our future health and wellbeing. Let’s make these our urgent priorities.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Previously in The Revelator:

Coronaviruses and the Human Meat Market

![]()