Over the past few years, many decisionmakers and forest managers have increasingly called for “active management” of natural forests — human intervention via mechanical thinning and other forms of commercial logging and road building — in response to increasing wildfires, beetle outbreaks, and intense storms. Many activists oppose these methods, saying they do more harm than good. For instance, actions that seek to suppress naturally occurring wildfires may make those fires more intense when they happen.

But active management activities have scaled up in response to economic drivers, misinformation on natural disturbance processes, and more climate-driven extreme events that trigger large and fast-moving fires.

We have published dozens of peer-reviewed articles and books on the impacts of active management on natural disturbance processes in forests. As active management begins to take on an even bigger role, conservation groups frequently call upon us to submit testimony, legal declarations, and science support. Meanwhile our key findings are often neglected by well-intended researchers who promote widespread active management but do not fully acknowledge the dramatic and often cumulative ecosystem consequences.

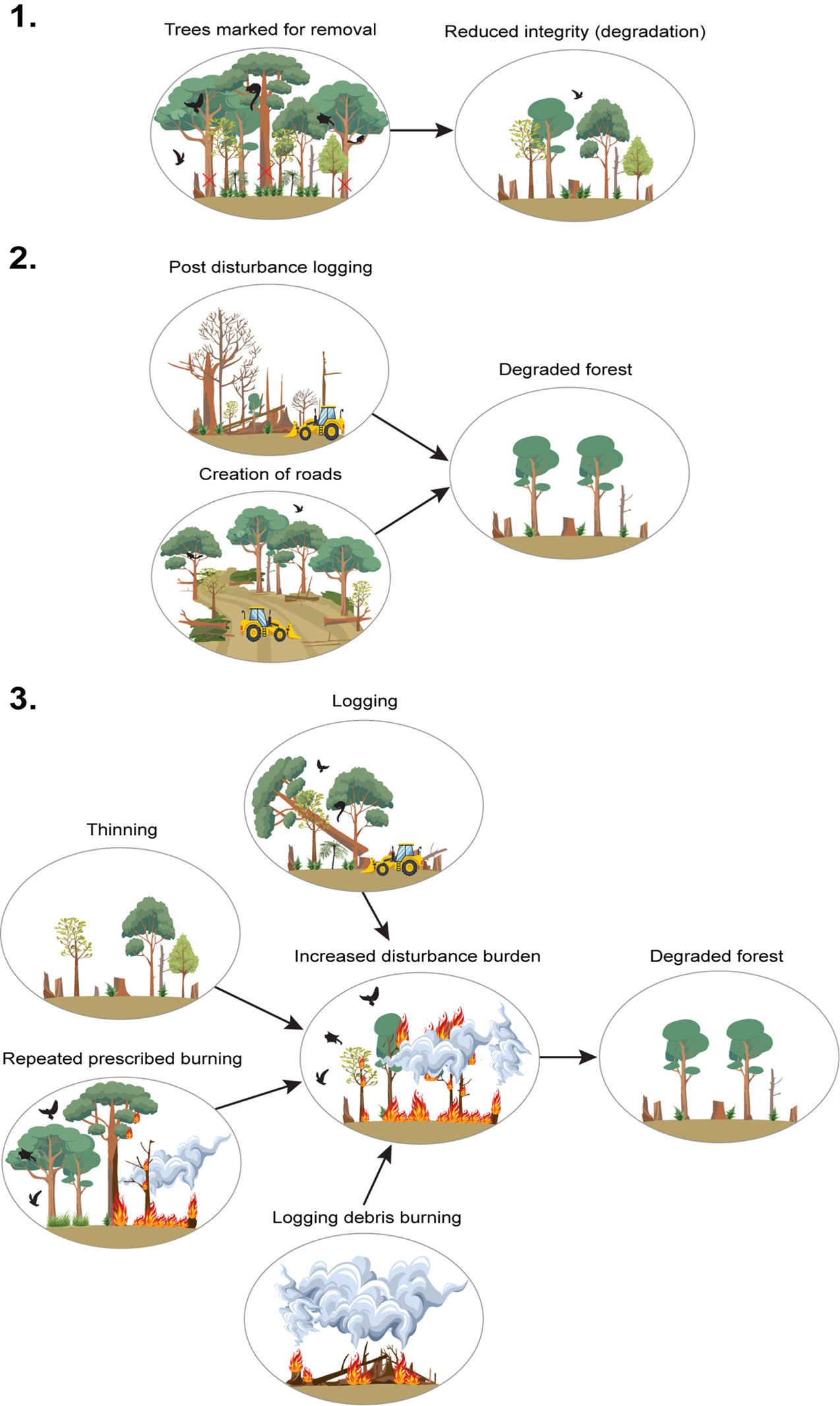

The active management activities we are most concerned about include:

-

- Clearcut logging of live and dead patches of trees, especially over large areas.

- Mechanical thinning of large trees via commercial removal.

- Too-frequent burning of forest understories, especially of logging slash in dense piles that cook soil horizons and encourage weeds.

- Post-disturbance logging that removes biological legacies (e.g., large live and dead trees) and damages natural processes and soils.

- Construction of major road networks that alter forest-hydrological connections, some of which are supposed to act as firebreaks.

Active management impacts depend on the intensity of removals, frequency and duration of impacts, and scale (site, landscape, ecoregion, biome) that often combine with the natural disturbance background in exceeding disturbance thresholds that degrade ecological integrity. Such practices have been widely accepted on at least three continents — North America, Australia, and Europe — where our research has been exposing severe impacts.

What Are the Ecological Costs of Active Management?

As we’ve shown in our recent studies, scaling up these types of activities comes with severe costs to natural ecosystems. The impacts of active management can even approach the effects of deforestation as they ramp up in application and intensity.

In the United States, this is especially apparent in relation to the recent executive orders that President Donald Trump announced under the rubric of a national timber emergency, cloaked in wildfire prevention. Even some progressive states, like California, have taken drastic measures to log vast areas with minimal environmental reviews in response to wildfires. Canada and European nations also have been driving up the active management rhetoric.

We used a series of case studies that demonstrated substantial negative and prolonged impacts of active management on a broad suite of ecological integrity indicators (including soil integrity, species richness, forest intactness, and carbon stocks) relative to more natural areas (reference sites). Active management, we found, is particularly consequential in high conservation value forests such as old-growth forests, intact watersheds, and complex early seral forests (“snag forests”) that follow severe natural disturbances but are rich in biodiversity. Such forests collectively play a pivotal role in maintaining ecological integrity while serving as natural climate solutions.

Natural disturbances are part of the necessary cycle of renewal and aging that has occurred in forests for millennia. There are well-documented patterns of forest rejuvenation following natural disturbances, even the severe ones, although we acknowledge that climate change is interacting with logging in a way that’s altering forest dynamics in places where forests may not come back on their own.

Natural disturbances create a pulse of biological legacies that sustain forest ecosystems for decades, including dead trees, surviving shrubs, fallen logs, and other structures that are associated with complex early seral forests and are not replicated by forest management. Many species, including some rare and threatened ones, are dependent on these legacies. The post-disturbance environment places the pioneering stage following a disturbance on a trajectory to old growth and then back again to the early stage when naturally re-disturbed.

We describe this process as “circular succession.” Active management can disrupt the natural flow of forest trajectories by breaking the cycle between rejuvenation and aging of forests such that forests never become old again (as in industrially logged landscapes).

Repeated thinning operations also remove key elements of stand structure such as large trees that are important habitats for a wide range of forest-dependent species. Often the large trees are relatively fire resistant and contain important adaptations such as epicormic branching near the crowns that allow the tree to survive and post-disturbance sprouting.

Our studies in Australian and western North American forests demonstrate that activities like commercial logging of large, old trees that are intended to reduce the severity of subsequent wildfires may have the opposite effect and increase fire severity and fire spread.

Similarly, there are cases where too-frequent prescribed burns on a site can alter the ecological condition of forest ecosystems in ways that, in the event of a subsequent wildfire, lead to significantly impaired forest regeneration and ecosystem type conversions to savannahs. This ostensibly is already underway in low productivity dry forests of the southern Rockies, which face a hotter, drier, and more frequent fire environment from natural and prescribed fires that together are ostensibly retarding forest renewal in places.

Active management may also increase the risk of high-severity wildfire by creating drier conditions that shift fuel types and fuel distributions, increasing fine fuels that dry quickly, while over-ventilating forests from the unravelling of intact canopies that otherwise buffer forests from high wind speeds associated with fast moving flames (as in the photo above).

Similarly, the construction of roads and firebreaks (chronic and cumulative disturbances) fragment landscapes and wildlife populations, paving the way for invasive species, and increasing the risk of human-caused ignitions (such as arson or accidental burns).

Impacts like these highlight the importance of understanding the overall disturbance burden in an area that accumulates from the combination of large tree logging, over-burning, livestock grazing, off-road vehicles, and road building, in addition the natural disturbances running in the background. Disturbance burden is a key issue that we highlighted in our recent research paper that is often neglected in active management circles.

An additional problem with active management is that tree removal or retention based on forestry prescriptions, particularly old growth or young trees establishing after disturbance, may reduce adaptation potential that would otherwise occur via natural selection that favors surviving trees better suited to the novel disturbance regimes resulting from climate change and insect outbreaks.

Simply put, foresters do not consider the genetic adaptations that are so crucial to forest persistence over time.

When Is Active Management OK to Use?

We acknowledge there will most certainly be cases where active management is a necessary part of ecological restoration practices that seek to improve ecological integrity and follow the internationally accepted precautionary principle (do no harm to native ecosystems).

Some examples include the control of invasive species that have colonized natural forests; removal of livestock and feral animals; replanting forests with native species where there has been natural regeneration failure or ecosystem type shifts underway; obliterating roads to increase connectivity and hydrological functions; upgrading culverts to handle storm surge; and reintroducing extirpated and keystone species (such as beavers).

However, other kinds of active management — like commercial thinning in high conservation value forests — may inadvertently accelerate degradation of these critical ecosystems with perverse impacts on biodiversity and carbon stocks. And while there are certainly cases where light-touch thinning (below-canopy, noncommercial) or prescribed fire alone can reduce high severity fire effects, the efficacy of tree removal in a changing climate is dependent on many factors, including extreme fire weather that is increasingly overwhelming treatment efficacy.

What’s Needed to Avoid Degradation?

Our precautionary approach to active management also underscores the significance of completing protection efforts that set aside large, representative protected areas (such as 30×30 and 50×50 campaigns) which, at a minimum, can serve as reference areas to gauge the efficacy and impacts of active management.

As we state in our research, this can be done using standardized metrics to assess the degree of degradation in comparison to reference sites along a continuum of relative loss. However, it must be understood that a complete assessment of active management on high conservation value forests, particularly attempts to recreate the later stages of succession, may not become realized for decades, if not centuries. Importantly, in some areas, reference conditions free of industrial activities and fire suppression may no longer exist and thus semi-natural areas may have to suffice as the reference for restoration.

We suggest that decisionmakers and managers invest in research that expands the understanding of natural disturbance regimes in forests, the effects of active management on ecological integrity (ecological restoration vs degradation), and that supports adaptive management strategies that are consistent with ecological integrity and conservation biology principles.

The bottom line: Active management needs a proper cost-benefit analysis to minimize trade-offs, lest the treatments may be much worse than the problems they seek to resolve. Our research daylights the expanding active management footprint while creating science support for decision-makers to choose more prudently on behalf of maintaining or restoring integrity and for activists to push back when policy is inconsistent with conservation science principles.

Previously in The Revelator:

Saving America’s National Parks and Forests Means Shaking Off the Rust of Inaction