Humanity now finds itself living in a world of its own creation, for better or worse. Our collective actions ripple out across the planet, taking a massive toll on all living things and their habitats, creating an uncertain future.

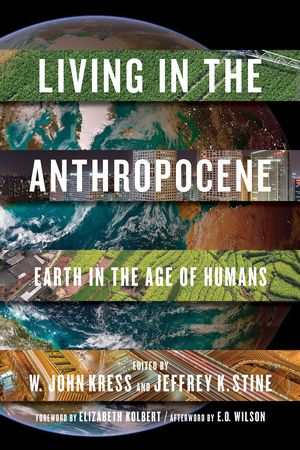

The “Anthropocene,” an era defined by lasting human impacts on the natural world, is a controversial epoch-labeling term still awaiting final approval by the International Union of Geologic Sciences. But reading the new book Living in the Anthropocene: Earth in the Age of Humans (Smithsonian Books, $34.95) leaves little doubt about how fundamentally we’re altering our world.

The “Anthropocene,” an era defined by lasting human impacts on the natural world, is a controversial epoch-labeling term still awaiting final approval by the International Union of Geologic Sciences. But reading the new book Living in the Anthropocene: Earth in the Age of Humans (Smithsonian Books, $34.95) leaves little doubt about how fundamentally we’re altering our world.

This comprehensive collection of essays from scientists, academics and other experts in their fields, edited by top curators at the National Museum of Natural History and National Museum of American history, covers myriad aspects of the human juggernaut.

Anthropogenic climate change — and the rising global temperatures, extreme weather events, ocean warming and acidification and sea-level rise that go along with it — is what many commentators associate with the dawning of the Anthropocene. But it’s just one part of how people have changed the Earth.

That’s evident in the opening essay, “The Advent of the Anthropocene” by Georgetown University professor J.R. McNeill, which dates the dawning of our new age to 1950 and includes a series of eight graphs to reinforce his point. Each one — “Marine Fish Capture,” atmospheric concentrations of methane and carbon dioxide, use of water and fertilizer, dam construction, energy use and urban population — shows slow, steady increases over decades or centuries turning sharply upward as prosperity returned following the horrors of World War II.

At that point, we mastered the art of creative destruction and applied it on an industrial scale, heedless of the cost or damage.

Similarly the closing essay, by renowned biologist E.O. Wilson, decries human impacts to the natural world that have increased the extinction rate 1,000 times, calling for us to drastically expand the amount of land protected from human impacts until it covers about half the planet, a level he considers relatively stable. Otherwise today’s greed will lead to a drastically altered world.

“There is a momentous moral decision confronting humanity today,” Wilson wrote. “It can be put in the form of a question: what kind of a species, what kind of an entity, are we, to treat life so cheaply? What will future generations think of those of us now alive having made such an irreversible decision of this magnitude so carelessly?”

In between those two contributions, World Bank officials Paula Caballero and Carter J. Brandon urge us to rethink our measures of economic progress; psychoanalyst Lindsay Clarkson talks about the psychology of environmental abuse; and art professor Subhankar Banerrjee discusses why the polar bear has become such an important cultural and artistic icon. More than two dozen diverse essays share their pages.

As the book discusses, new technologies and ways of working have allowed us to harvest crops, seafood, meat, oil and minerals at previously unimaginable levels for a skyrocketing global population. But the tradeoff has been equally high levels of pollution, habitat loss, resource depletion and the sixth mass extinction event in our planet’s history.

Speaking of which, journalist Elizabeth Kolbert, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Sixth Extinction, contributed the foreword to Anthropocene. “The more we understand about our impacts, and our impacts’ impacts, the more urgent the questions become,” she wrote. “What should we do with this knowledge? Should we scale back our influence? Can we?”

These are good questions, and she’s right that they urgently demand answers. Our current course is unsustainable, whether we’re looking at our economic system, the energy sector, food and water supplies, social systems, the ability of the ocean and atmosphere to continue absorbing our emissions, or any of the other realms this book explores.

The essays in this collection can be a bit dense and academic, so it’s not always the easiest read. But the expertise and research reflected in these pages is impressive, explaining in startling detail the complexities of how our world is changing, and how we’re processing that change in our science, art and politics.

Everyday one can read about some aspect of the planet that humankind is disrupting “and it’s a wake up call”.

Sorry, no one is waking up to anything but more bad news tomorrow. We’re already using over 50% of the non-ice covered land on the planet for our purposes, so, giving up grazing, or, highways, or cities in order to meet Dr. Wilson’s 50% goal for wildlife already is hugely disruptive to human purposes.

Plastics may be the part of the geological record that will best reflect our age (projected to outweigh fish in the sea by 2050…).

(How much open ocean fish were responsible for human nutrition over the course of our evolution? A very small percentage, yet we presume that we can ‘manage’ fisheries for a food source, without considering what evolved to eat those fish if we didn’t cull them.)

Yes, the extinctions are formidable, but we’ve also reduced animal and fish biomass by 50% in the last 60 years, which will only get worse as our 7.5Bn goes to 9 or 10Bn (if we aren’t already extinct by then).

Few realize how much our current trajectory is affecting the planet, but the recent news of the decimation of insect biomass from Germany is far more than a wake up call, it may be lights out.

My analysis suggests it is immoral for anyone, anywhere to have children, anymore.

vhemt.org