If things go according to plan, the sight of a leaping dolphin in the Gulf of California could be a sign of hope for the critically endangered vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus).

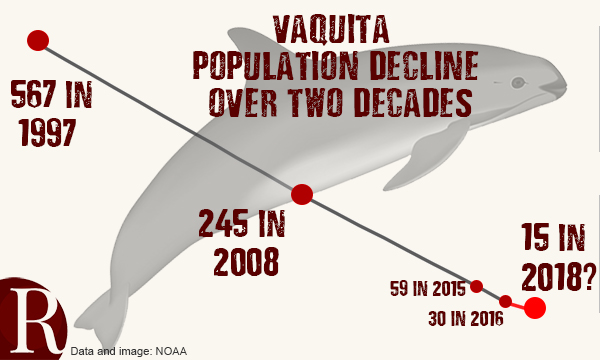

Only about 30 of these rare, tiny cetaceans remain, and their numbers are falling fast due to rampant illegal fishing in the area. Many conservationists fear the species could become extinct in the next year or so without drastic conservation efforts.

That’s where the larger bottlenose dolphins come in. Used by the U.S. Navy to locate so-called “aggressive swimmers” in combat situations, the dolphins have been trained to leap into the air when they encounter their targets, providing a visual cue for watchers on nearby ships.

That’s where the larger bottlenose dolphins come in. Used by the U.S. Navy to locate so-called “aggressive swimmers” in combat situations, the dolphins have been trained to leap into the air when they encounter their targets, providing a visual cue for watchers on nearby ships.

A 2004 Navy press release describes how the dolphins are used in wartime: “Due to their hydrodynamic shape and a highly effective biological sonar system, the bottlenose dolphins are uniquely equipped to detect, locate and mark underwater threat swimmers, divers, and swimmer delivery vehicles, through a process called echolocation, in which the dolphins emit broad-band high frequency clicks and listen to the echoes of those clicks as they bounce off objects.”

The dolphins’ natural abilities will complement more technological efforts to local the vaquitas. “The dolphins’ echolocation goes out 200 meters or so,” Barbara Taylor from the National Marine Fisheries Service and the Consortium for Vaquita Conservation, Protection, and Recovery (VaquitaCPR), told me this past June. “We can see them with binoculars out to about 1,500 meters. So, we’ll have a much larger sweeping pattern than the Navy dolphins will.” The dolphins, however, may be able to initially get much closer to their endangered cousins than ship-based observers. “One of the difficult things about vaquitas is that they move away from motorized vessel noise,” Taylor said.

If the dolphins do spot any vaquitas, conservationists will rush in to try to remove them from the water and relocate them to a specially constructed saltwater pen. In that protected environment, it’s hoped, they’ll be safe from illegal fishing nets and may be able to start breeding.

The team, made up of international conservation groups and government agencies, hopes to eventually rescue 12 vaquitas, although right now no one knows if the animals will even survive in captivity.

“If the animals cannot accept care by humans, if they are not able to adapt to our care, we will put them back,” Cynthia Smith, executive director of the U.S. National Marine Mammal Foundation, told the Orange County Register. “We do not ultimately want to cause them harm.”

The plan has earned its critics, some of which point out that dolphins have been known to kill porpoises in the wild (even the Navy considers their dolphins too dangerous to allow trainers to swim with them). Others say this action seems more intended to save the Navy’s expensive Marine Mammal Program rather than the vaquitas themselves.

Even those that support the plan — including the Center for Biological Diversity, publishers of The Revelator — point out that rescuing any vaquitas from the Gulf of California will ultimately be pointless if the Mexican government does not step up efforts to eliminate illegal fishing in the area.

Regardless of the uncertainty and criticism, this next year represents what could be our last chance to save the vaquita from extinction. We’ll be waiting for news of those leaping dolphins and the animals they could eventually rescue.

Previously in The Revelator:

Last Chance to Save the Vaquita?