TUCSON, Ariz. — If you’ve ever walked down a city street on a sweltering summer day, you know what a welcome relief it is when you reach a tree’s canopy. Both physically and mentally, that shade is a natural resource.

Like so many other resources, though, shade often goes to the privileged. The richer the community, many studies show, the more likely they are to have trees that provide a cooling respite.

Around the country local governments have launched efforts to address this inequality by measuring shade equity — equal access to the cooling benefits of tree cover. It’s an index of inequality and an issue of climate justice.

In the heart of the rapidly heating Sonoran Desert, providing equal access to the cooling benefits of tree cover can make the difference between life and death.

View this post on Instagram

“Planting trees is a meaningful, tangible thing that people can do to fight climate change,” says Nicole Gillett, Tucson’s urban forestry program manager.

While southern Arizona is a region better known for its cacti, native trees have fed and shaded desert dwellers for centuries. Trees everywhere have been shown to raise people’s happiness, reduce crime, muffle noise, and support more wildlife.

And now more than ever, humans need them.

Deadly Inequity

In a 2021 paper, a team of public-health, remote sensing, and landscape scientists looked at mean temperatures in 20 Southwest cities from Sacramento to Houston. On an average summer day, in all 20 cities studied — including Tucson — temperatures were significantly hotter in poorer and more Latino neighborhoods than in richer, whiter ones.

A lack of green space causes these temperature disparities, according to the researchers.

Poorer neighborhoods often have fewer trees and more rock and gravel, which absorb heat and make the surrounding air hotter. Large, paved areas and densely built areas do the same, creating an urban heat island effect that boosts neighborhood temperatures. Across the country low-income neighborhoods have fewer trees than high-income neighborhoods in 92 % of U.S. cities, according to a study by Robert McDonald, lead scientist for nature-based solutions at The Nature Conservancy.

In Tucson, Gillet says, seven of the 10 hottest neighborhoods are on the city’s Southside. This is where social demographics and urban heat intersect, since South Tucson is one of the poorest parts of town as well as a Latino stronghold. The 2021 study found that on an average summer day, temperatures in the hottest Southside neighborhoods exceeded citywide averages by 7 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit.

When compared to the Catalina Foothills — one of the metro area’s most affluent regions — the temperature disparity ran as high as 12 degrees.

It’s no surprise. The city’s shadiest neighborhoods are also often its most well-heeled, Gillet says, their residents less vulnerable because they’re likelier to have access to air conditioning — and be able to pay the electric bills to keep it running.

In hotter neighborhoods, on the other hand, residents with the highest heat burden have the fewest resources to mitigate that heat.

Extreme heat can be deadly, especially for vulnerable populations like the elderly, the unhoused, and those with preexisting medical conditions. In contrast to headline-grabbing natural disasters, extreme heat has been called “the silent killer,” and Arizona is its deadly epicenter. While the rate of heat-related deaths rate has roughly doubled in the United States in the past 20 years, Southern Arizona’s heat-related deaths have increased tenfold.

Two trends drive the epidemic: rising temperatures and people’s rising vulnerability to the heat. Homelessness has exploded in urban Arizona since 2015, and the risk of heat-related death for unsheltered people may be 200 to 300 times that of other people.

But while the current swing in temperatures between the coolest and hottest neighborhoods is already wide in many cities, the mercury tells only part of the story.

“For a city like Tucson, that isn’t the most effective way to measure heat,” Gillett explains. “If you’re standing under a tree next to a wash in Tucson, it could be 100 degrees but feel like 80 or 90 degrees. But if you’re standing on concrete, next to an asphalt road, under a metal bus shelter, that feels like 130.”

View this post on Instagram

Mapping Shade Equity

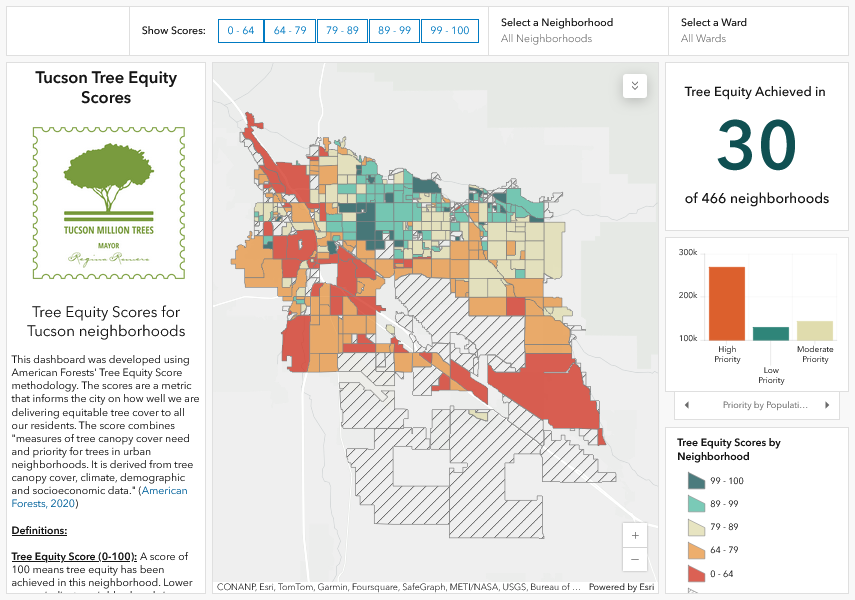

To achieve better shade equity around the country, the nonprofit American Forests launched an online tool in 2021 to score geographic regions based on tree canopy and surface temperature as well as income, employment, race, age and health factors. It calculates a Tree Equity Score for each neighborhood that allows planners to identify areas with the greatest need for trees.

Today, Gillett says, “Any major city utilizes this methodology for looking at tree equity.”

Gillett is Tucson’s first urban forestry program manager — hired in late 2020 to help cultivate its green space. Yet when she began her job a little over four years ago, the concept of shade equity, along with the tools and programs for achieving it, were still new. So, she acknowledges, “We’re flying the ship here as we build it.”

Using this technology along with federal data, the Tucson government created its own Tree Equity Dashboard, a map that identifies where it should prioritize tree planting. The map color-codes each neighborhood, on a scale moving from green to red.

Not surprisingly, the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods score the highest, due in part to vegetation and in part to that wealth — better access to other cooling resources.

“My goal is to reach tree equity across the entire city,” Gillett says. “That will look and feel very different across the city. Within a neighborhood itself, I want it to be as practical and mean as much as it can.”

In practice, that means putting more trees where people live.

“If you’re walking down the sidewalk to school, that tree is going to be more helpful than if it’s planted in the middle of a park,” she says.

A Million Trees

As with all the best proverbs, this one still holds true: The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The next best time is now.

In 2020 Mayor Regina Romero launched Tucson Million Trees, an initiative whose goal is to increase the city’s tree canopy by planting, yes, a million trees by 2030. Residents and businesses fund the effort through their monthly water bills; the city collects a “green infrastructure” fee of $0.13 per CCF of water used. This fee supports the city’s Storm to Shade program, which funds tree plantings and water harvesting efforts.

The city has already planted 120,000 trees over the past four years, at a rapidly increasing annual rate.

“We’ve almost doubled every year what we’re planting,” Gillet says. “We could just go out and plant a million trees, but as someone with scientific ethics, I wanted first to implement standards and tracking and training.”

Tree planting success assumes tree survival at a time when some cities are struggling to keep alive the trees they already have. To successfully establish trees in a desert city, Gillet says, each tree planted must be a tree that someone agrees to water, at least until it becomes established. The city can’t care for them all. This means the trees need to put down roots where residents can water them, at least initially.

“They need to be on irrigation for two years while getting established, or hand-watered,” explains Joselyn Aguilar, community engagement and education manager for Watershed Management Group, one of the local nonprofits working with the city.

But in some low-income neighborhoods, most of the homes are rentals. This limits people’s interest in long-term planting efforts, and absentee landlords are often uninterested, too.

“We don’t just want to plant a tree that nobody wants or takes care of,” Aguilar says. “This is where education and community engagement come in. We want to show people why these plants are important and [help them] become stewards of the trees.” She recently helped plant some trees at a Boys & Girls Club on the Southside, which promised to hand-water the plants for the next two years.

Similar efforts are playing out across the city.

“I really like to emphasize that all these plants we put in the ground are alive,” Gillett says. “They are the only piece of infrastructure that grows in value over time because they are alive.”

And because they are alive, some people grow attached to them. “People really care for trees. We develop relationships with trees,” but each neighborhood must commit, she adds. “People think of planting trees as this straightforward, easy thing … but an urban tree is going to have a harder time than its counterparts right away. The more people who have a stake, who are involved, the better.”

And this isn’t about planting decorative trees beloved by landscapers and developers. Tucson’s effort favors trees that are adapted to the Sonoran Desert, including velvet mesquites, palo verdes and ironwood trees, which have some of the hardest wood in the world and can live up to 800 years.

“We want to make sure it’s native plants,” Aguilar says. “One of the benefits is … recreating our native ecosystem.”

Trees vs. Trump

Tucson’s tree equity program — and other efforts in nearly 400 other communities around the country — received a big boost in September 2023 when the U.S. Forest Service announced it would award more than $1 billion in competitive grants to plant and maintain trees in urban areas in all 50 states to combat extreme heat and climate change and improve access to nature. Tucson received $5 million to invest in neighborhoods on the frontline of climate change.

By focusing on a handful of the city’s hottest neighborhoods, Grow Tucson, which just launched this year, works in synch with the Million Trees goal. The mayor’s program is broader in scope, citywide, but both are committed to shade equity and creating green spaces, especially in frontline and low-income communities.

The Forest Service issued the grant through its Urban and Community Forestry Program, begun in 1978 to assist states and partner organizations in applying nature-based solutions to both chronic and emerging challenges. But the grant money originates from the Inflation Reduction Act, the ambitious Biden administration law that channeled billions of dollars to climate action.

The current administration wants to stop that spending and maybe repeal the whole act.

What’s more, the Trump administration considers equity — shade or otherwise — a dirty word. President Trump has issued several executive orders aiming to dismantle diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives within the federal government.

The Trump administration has also denied access to critical federal data, including the Climate & Economic Justice Screening Tool, a tool to help implement President Biden’s Justice 40 initiative, which set a goal that 40% of the benefits of certain federal investments would flow to disadvantaged communities. Gillett and her team utilized CEJST and the American Forests tool to identify which Tucson neighborhoods to prioritize.

And the Trump administration may yet deny funding to the entire Forest Service initiative. In Oregon recipients of the same grant funding are seeing their invoices go unpaid due to President Trump’s freeze of IRA funds. As a result folks there are cutting budgets and staff. In New Orleans a terminated grant to the Arbor Day Foundation has left a local foundation, Sustaining Our Urban Landscape, without the funds to water 1,600 trees they’ve already planted in low-income communities.

Asked about the status of Grow Tucson’s funds, Gillett wrote, “As of [March 4], we have not received any formal word from the Forest Service and our program is proceeding.”

View this post on Instagram

Fortunately Tucson and other hot cities still have access to American Forests’ methodology. Tucson also has its customized Tree Equity Map, which it created before CEJST was taken down. And it still has a lot of people dedicated to making Tucson a livable city for everyone. So even if the Trump administration pulls the plug on Grow Tucson, the city will keep planting trees.

The goal for Grow Tucson is 20,000 trees, plus 11,000 native pollinator plants. (A 2024 study found that enhancing total greenness, not just canopy cover, is the most effective strategy to reduce urban heat.) That’s a drop in the city’s Million Trees bucket, but a good drop.

Without it, Aguilar says, “We wouldn’t be able to dedicate those resources to those neighborhoods that have no shade.”

And while the Trump administration attempts to reverse every gain this country has made battling climate change, she adds, “Tucson and the world are getting hotter.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Tree Cutting in Egypt: The Desertification of Governance