In late September 2023, a one-mile stretch of the Trinity River in northern California looks and sounds like a construction site. Large yellow machines crawl across bare ground, the steady growl punctuated with warning beeps. Behind pyramids of stockpiled materials — mulch, gravel, logs — the river flows serenely.

Aldaron McCovey manipulates his excavator, using the back of the bucket to deftly smooth out fine material on a bare new bank.

“It was a little overcut, so we’re filling it in so that there’s no standing water,” he explains.

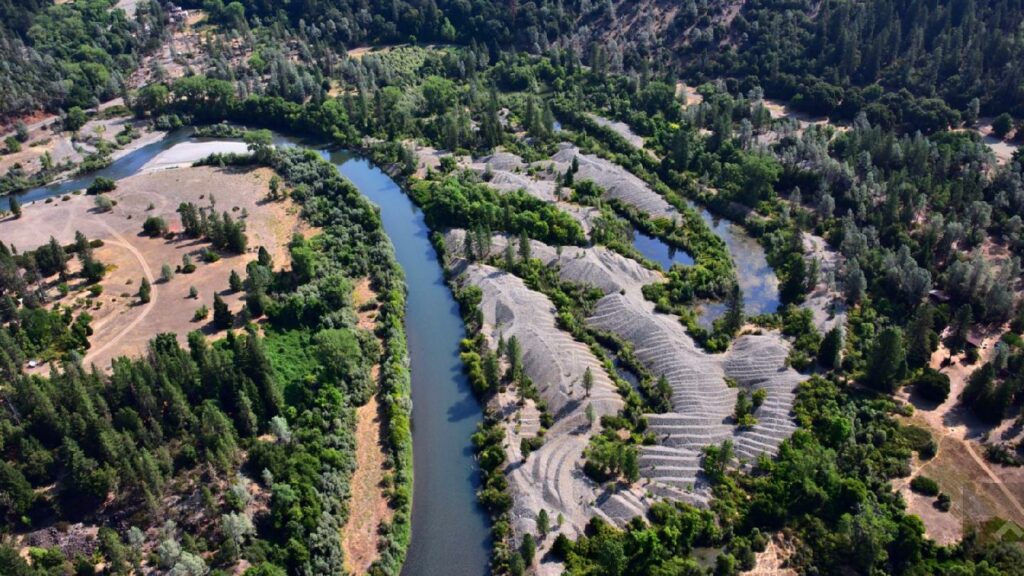

A fisheries restoration technician for the Yurok Tribe, McCovey is working on an ambitious restoration project called Oregon Gulch, just east of Junction City, Calif. Here, crews from the Yurok Tribe Construction Company are rerouting a straightened stretch of the Trinity River into a newly sculpted meander to help restore the river’s form and function.

Getting to a clean slate required moving mountains of cobbles and gravel — the legacy of 20th-century dredge mining. Seventy years ago, monstrous machines chewed through river and valley, funneling rocks, mud, sand and water into a sluice, extracting the gold and dumping the spoils behind in pile after pile after pile.

“This time last year we’d be standing on 30 feet of tailings,” says McCovey. “It was like a dead zone.”

In August 2022, a procession of trucks began transferring the tailings to a quarry half a mile down the road. In total, they have removed 580,000 cubic yards of material from the site — a staggering 30,000 truckloads.

Now large machines are once again moving through the valley, this time with the aim of creating floodplain habitat that will sustain young salmon before they migrate to the ocean.

“We have this nice meander, some deep holes and some off-channel habitat,” says McCovey. “I think it’s going to be great for fish.”

The project is part of the Trinity River Restoration Program, a long-term collaborative effort involving the Yurok Tribe, Hoopa Valley Tribe, and state and federal agencies to restore 40 miles of the Trinity River below Lewiston Dam. Oregon Gulch is the partners’ 40th project; it’s also the largest, and the first to take on the legacy of dredge mining at such a scale.

A River Turned Upside Down

The Trinity River originates in the granite Trinity Alps, flowing 165 miles before joining the Klamath River in Weitchpec, Calif. For thousands of years Indigenous peoples — ancestors of today’s Hoopa River and Yurok Tribes — fished the river.

Gold seekers first arrived in 1848; before long, they had set up mining operations on every bar of the river, using water wheels, diversion dams, water cannons and finally, large dredges to extract every ounce of precious metal.

The massive floating platforms worked the Trinity and its larger tributaries, chewing through valley bottoms down to bedrock. The operation literally turned rivers upside down, and while much of the sediment washed downstream, some of the finer material lay trapped underneath gravel and larger cobbles.

In 1955 mining was supplanted with another catastrophe when Congress concluded that excess water in the Trinity River that was “wasting to the Pacific Ocean” could be diverted to the Central Valley “without detrimental effect to the fishery resources.” By 1963 two dams had been built and the Trinity River Diversion began transferring water to the Sacramento River watershed.

The dams blocked over 100 miles of habitat for salmon and steelhead, and in the early years, 90% of the water impounded by the dams was diverted to the Central Valley Project. What little water was sent downstream was artificially managed. Flows flatlined, and the river no longer ebbed and flowed with the seasons and storms.

Chinook and coho salmon and steelhead plummeted. As the consequences of the diversions, compounded by mining and logging, became clear, the Department of Interior began amending its management strategy, and in 2000, the agency called for the restoration of Trinity River anadromous fish populations. The Trinity River Restoration Program was set up to carry out the directive by actively restoring the 40 miles below Lewiston dam and managing the timing and volume of water released from upstream.

Letting the River Decide

The Yurok Tribe has been implementing those restoration projects for years; in 2020, the Yurok Tribe Construction Company officially formed as a separate entity. The company occupies a specialized niche, with operators like McCovey who have years of experience operating heavy equipment specifically for restoration work.

To help fund the $12.5 million project, the Yurok Tribe captured a $4 million grant from the state of California. The Tribe also led the design, though, like all of the program’s projects, all of the partners were involved.

The most engineered aspect of the project is a constructed landslide, called the “plug,” designed to prevent the river from routing back into the straight channel.

“The bulk of cost was material moving,” says Chris Laskodi, fish ecologist for the program. “It’s one of our simplest designs because we’re basically telling the river to do what it wants to do.”

A newly created floodplain is designed to sit just above the river level.

“That’s the exciting part,” says Wes Scribner, executive director of the Yurok Tribe Construction Company. “Any time you have increased flows, it will basically turn into a lake.”

The inundated valley will host an abundance of aquatic insects — a banquet for young Chinook salmon to feast on before heading out to the ocean. An area like this will also be warmer in spring, an ideal nursery when the mainstem of the river is still frigid from snowmelt.

Eventually the river will find its own route, depositing trees, brush and rock along the way.

The partners have seen a four-fold increase in juvenile salmon on the 40-mile “restoration reach” since 2005, but this hasn’t translated into an increase in adults returning to spawn just yet. Poor ocean conditions, prolonged drought and perennial water-quality issues on the Klamath River have taken a grim toll. Last spring, in anticipation of woeful returns of adult salmon to California’s rivers, the state canceled commercial and recreational Chinook salmon fishing for the year.

There is hope: By the end of 2024, four dams on the Klamath River will be completely removed. This monumental act of restoration should help improve water quality and hopefully reduce fish diseases, eventually translating into more fish on both the mainstem and tributaries like the Trinity. In the meantime, project partners on the Trinity are using adaptive management to improve their projects, such as making sure floodplains are low enough to be regularly inundated.

They’re making other tweaks, too, like ensuring that the floodplain banquet is available when young fish need it most. Today the Trinity River is allotted about half of the water that’s captured by the dams, and springtime flows are managed to mimic surges from storms and snowmelt.

In 2023, for the first time, the partners increased flows earlier, from February to April. Though it’s hard to draw solid conclusions from a single year, the partners observed that the inundated floodplains grew more fish food and increased the physical space where young fish can be. Fish also grew measurably larger.

This timing is critical.

“We need to start using the water [we have allotted to us] earlier in the year,” says Mike Dixon, executive director of the Trinity River Restoration Program. “In any given year, 60 to 80% of Chinook have left the reach once we start putting water onto floodplain habitat we’ve created.”

The Hoopa Tribe has opposed the winter flows out of concern that the practice won’t leave enough water to keep the river from becoming lethally warm in summer. The Trinity Management Council voted against implementing variable flows this coming winter. However, new biological opinions for both the Central Valley Project and for the operation of the Trinity River dams are being developed, which could impact both the timing and volume of water the restoration partners have to work with.

“The trend has been to send more and more water down the Trinity River,” says Laskodi. “This will hopefully be the next step towards a better fishery.”

Green and Fuzzy

For half a century, the flows in the Trinity River were essentially flatlined. This meant that narrow-leaf willows, which grow closest to the riverbank, were not subjected to regular scouring. The willows grew in thickly, outcompeting other plants and creating narrow berms that prevented the river from spreading out into its floodplain.

During construction, a crew from the Hoopa Valley Tribe began planting clusters of willow stakes and cottonwood trees, which readily take root, in the bare banks. They are using several different native species, since each thrives at slightly different elevations above the river.

On October 15 when the dumping, spreading and scraping of material ceased, the crew began the quiet work of seeding and planting the raw banks and floodplain. The Tribe has been vegetating the program’s restoration projects since 2015. Under the direction of riparian ecologist Veronica Yates, they are working with 45 native species, planting shrubs and trees and using seed mixes tailored for each location. The vegetation will help support a variety of birds and wildlife while reducing erosion.

Over much of the site, they’re planting in a layer of fine material mixed with fragrant wood chips — a “luxury” compared to the substrate they usually work with, says Yates. The fine material was recovered from the tailing piles; the chips from fire-killed trees processed by the California Department of Transportation.

“Next spring we’ll come back and it will be all green and fuzzy,” says Scribner. “That’s the neat thing about our projects; over time, it’s getting harder and harder to tell what it used to look like.”

Previously in The Revelator:

A Lifeline for Winter-Run Chinook

![]()