Billions of people around the world rely on the ocean for food, income and cultural identity. But climate change, overfishing and habitat destruction are unraveling ocean ecosystems.

As a marine ecologist, I study ways to improve ocean conservation and management by protecting key areas of the ocean. Many nations have created or promised to create marine protected areas — zones that may restrict activities like fishing, shipping and aquaculture. But decades of research have shown that not all marine protected areas are created equal, and that the most effective preserves restrict damaging activities.

Tallying Pledges

Many governing bodies around the world have responded to the ocean crisis by pledging to protect swaths of ocean within their territories. To see how these commitments added up, my colleagues and I recently evaluated ocean conservation commitments announced from 2014 through 2019 at the yearly Our Ocean Conferences — high-level international meetings initiated by the U.S. State Department. (More recent meetings were canceled during the COVID-19 pandemic.)

A number of countries have made ambitious commitments. At the Our Ocean Conferences from 2014 through 2019, 62 countries pledged to protect areas of their ocean. Fourteen nations, including the Seychelles and Chile, committed to protect more than 38,000 square miles (100,000 square kilometers) within their waters.

Unfortunately, even if all of these commitments are fully implemented, they will protect only 4% of the world’s ocean. Adding in all other protected areas and outstanding commitments made in other forums raises that figure to 8.9%.

The number is likely to rise as additional countries join in. For example, on May 30 the South Pacific island nation of Niue pledged to protect 100% of its national waters. They cover 122,000 square miles — an area roughly the size of Vietnam.

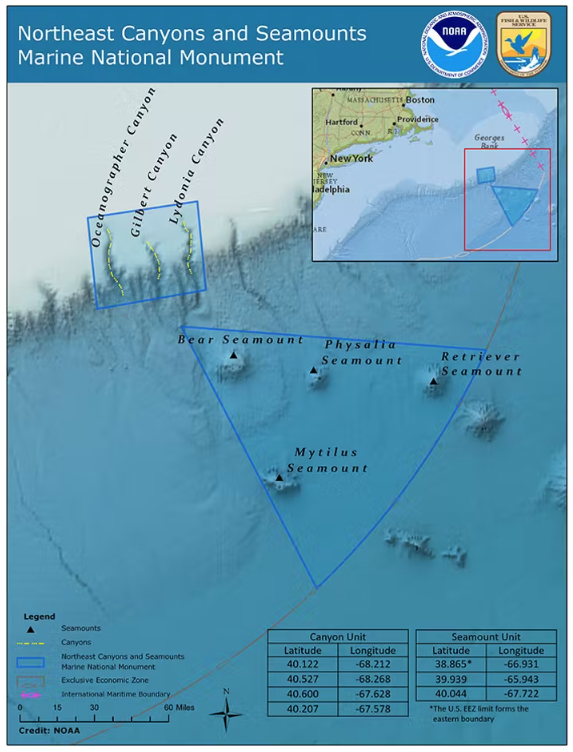

Most recently, the Biden administration proposed on June 8 to designate Hudson Canyon, which lies southeast of New York City in the Atlantic and is one of the largest underwater canyons in the world, as a national marine sanctuary. The canyon provides habitat for sperm whales, sea turtles, deep-sea corals and other sensitive species.

Adding urgency to this effort, negotiations at the United Nations continue around a proposed target to protect at least 30% of Earth’s land and sea areas by 2030. More than 90 countries, including the U.S., have endorsed this goal.

Clearly this is strong progress, but much work remains. Nations have failed to carry out past international conservation pledges. And meaningful marine protection involves more than stating high-level commitments.

Promises, Promises

Today some marine protected areas offer significant protection for fish and other sea life, but others exist mainly on paper.

For example, the Southern Ocean around Antarctica is one of the least-altered marine zones on Earth, but fishing is expanding there, and only 5% of it is currently protected. Deliberations over two proposed protected areas there, in the East Antarctic and the Weddell Sea, have continued for years.

In many protected areas, damaging activities are permitted. For example, the Habitat Protection Zones of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park allow multiple types of fishing.

I served on an international team that published a broad framework for planning and assessing marine protected areas in 2021. Our key message was that effectively conserving ocean habitats and marine life will require working together with local communities and governments to create more marine protected areas and set tighter curbs on destructive activities.

We designed this guide to provide an accurate, science-based picture of how much actual conservation these protected areas will deliver. It complements the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s well-established categories for protected areas — guidelines that the United Nations and many national governments use for defining protected areas.The IUCN categories describe types of management at various sites. For example, a Category II national park sets aside large swaths of land or sea. But the categories don’t specify what kinds of activities are allowed there or describe their impact. Our guide adds four new elements that are particularly relevant for tracking and decision-making.First, it identifies whether a protected area is simply a concept, an operational area with effective governance and regulations, or something in between. This is important, because it can take years to move from drafting a proposal to actually conserving a swath of ocean.

Second, the guide outlines four levels of protection: 1) fully protected, with no destructive activities allowed; 2) highly protected, with only minimal human impacts; 3) lightly protected, with moderate impacts; 4) minimally protected, with destructive activities allowed.

This last category can still qualify as a protected area if conserving biodiversity is its primary goal and no industrial activities, like mining and drilling, are permitted.

Third, successful marine protected areas must be planned, designed and managed equitably. An open process is crucial to earn public support. This includes co-managing and incorporating traditional knowledge from Indigenous peoples and the experience of local fishers and other people who use the area.

Finally, once a marine protected area is established, it needs to receive adequate political support and financing, particularly for projects that rely on international investment.

Raising the Bar

Applying these criteria will help policymakers develop more effective marine protections and assess what existing protected areas are accomplishing. For instance, measured by these standards, we found that only 3% of all existing and pledged marine protected areas from Our Ocean Conferences would be considered fully or highly protected.

Experts in Canada, Indonesia, the U.S., and other countries are already using this guide to evaluate existing marine protected areas so that communities and governments can make informed decisions and adjust policies accordingly.

While ocean protection has far to go, I see reason for optimism. At the most recent Our Ocean Conference, in the Pacific island nation of Palau in April nations made more than 400 new commitments to take steps including creating new protected areas and reducing marine pollution and illegal and unregulated fishing.

These pledges involved some $16.35 billion in funding, on top of $91.4 billion already committed at previous conferences. I believe that if nations use these resources to create the kind of high-quality protected areas described in our guide, there is great hope for conserving ocean life.

Vanessa Constant, associate program officer with the Ocean Studies Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Previously in The Revelator:

The Top 10 Ocean Biodiversity Hotspots to Protect