I write about real-life environmental horrors every day, but at night I often escape from reality by reading horror fiction.

It’s not about thrills and chills or blood and gore. Horror stories, at their best, reflect the world around us. They take our personal or societal fears and turn them into something that we can process from the relative safety of our homes or movie theaters.

And what a world of fears we have today. We live in an era of climate change, deregulation of pollution, assaults on public lands and mass extinction. That’s worse than any zombie, serial killer or eldritch demon.

It’s an alarming world, and that’s echoed in our fiction.

But even the horror writers who tap into these existential dreads have their own fears to face. So I turned to some popular horror novelists and asked:

What environmental issue scares you the most?

Their answers may give you a chill.

Jeff VanderMeer, author of Borne and the Southern Reach trilogy:

“Honestly, what scares me most is silence. The idea of silence in the world because the animals are gone, the birds are gone. I have nightmares in which I wake up in the morning and instead of the call of jays and cardinals and sparrows, there’s nothing. That the communal chatter that we take for granted and think will always be there…is gone, and we created the circumstances by which it went away. I can think of nothing more horrifying than the sound of our own voices without some counterbalance in the world.”

“Honestly, what scares me most is silence. The idea of silence in the world because the animals are gone, the birds are gone. I have nightmares in which I wake up in the morning and instead of the call of jays and cardinals and sparrows, there’s nothing. That the communal chatter that we take for granted and think will always be there…is gone, and we created the circumstances by which it went away. I can think of nothing more horrifying than the sound of our own voices without some counterbalance in the world.”

Stephen Graham Jones, author of more than 20 books, most recently the werewolf novel Mongrels:

“Used to be, our zombie stories were about loss of autonomy. These days, they’re more about severely limited resources. When we see a dozen zombies trying to feed off one person, we’ve nearly got to read those zombies as figurations of ourselves — specifically, what we’ll be reduced to when we’ve used up and poisoned all the drinking water. So, the question for us right now, is the zombie story going to have been a cautionary tale for us, or an instruction manual? I would hope the former, but it’s hard not to see the latter already becoming reality. Best that we savor every drink now. Maybe even best if we write down the sensation of stepping into a swimming pool, a bath, a sprinkler, or sitting through a carwash, or watching a water show at a casino. Our writings of those sensations may very well be the only record, before too long.”

“Used to be, our zombie stories were about loss of autonomy. These days, they’re more about severely limited resources. When we see a dozen zombies trying to feed off one person, we’ve nearly got to read those zombies as figurations of ourselves — specifically, what we’ll be reduced to when we’ve used up and poisoned all the drinking water. So, the question for us right now, is the zombie story going to have been a cautionary tale for us, or an instruction manual? I would hope the former, but it’s hard not to see the latter already becoming reality. Best that we savor every drink now. Maybe even best if we write down the sensation of stepping into a swimming pool, a bath, a sprinkler, or sitting through a carwash, or watching a water show at a casino. Our writings of those sensations may very well be the only record, before too long.”

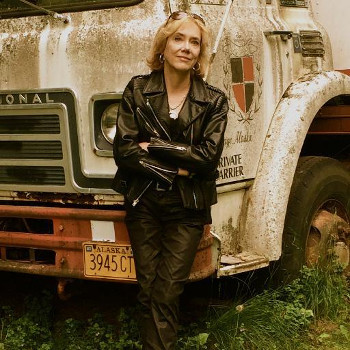

Elizabeth Hand, author of Hard Light and Wylding Hall:

“I have nightmares about the wasteland. T.S. Eliot’s was vast, but a wasteland can also be pocket-sized. These small ruined landscapes are more insidious, because we don’t necessarily recognize them as blighted. A vernal pool eradicated by agriculture or a golf course, a new housing development or a careless backyard renovation, means no breeding ground for amphibians, which means another sort of silent spring than the one Rachel Carson imagined: an April where no peepers or wood frogs or toads or tree frogs sing, and no salamanders lurk under rocks to be discovered by wide-eyed children.

“I have nightmares about the wasteland. T.S. Eliot’s was vast, but a wasteland can also be pocket-sized. These small ruined landscapes are more insidious, because we don’t necessarily recognize them as blighted. A vernal pool eradicated by agriculture or a golf course, a new housing development or a careless backyard renovation, means no breeding ground for amphibians, which means another sort of silent spring than the one Rachel Carson imagined: an April where no peepers or wood frogs or toads or tree frogs sing, and no salamanders lurk under rocks to be discovered by wide-eyed children.

“We fall in love with the natural world when we’re young, but what happens when we no longer have access to it, when we turn over every rock to find nothing beneath? What happens when fear — of things like tick- and mosquito-borne disease and exposure to UV rays, pesticides, predatory humans or wild animals — keeps us indoors, and the natural world is supplanted by a computer-enhanced vision of wilderness we can explore without risk or a responsibility to protect it? ‘A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,’ Eliot wrote, ‘And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,/And the dry stone no sound of water.’ Look to where the bulldozers are making way for that clubhouse, and I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

Jonathan Maberry, author of Patient Zero and Dogs of War:

“I write weird science thrillers for a living and am always jolted when the real world out-weirds what I write. The greed-driven resistance to the overwhelming scientific consensus about climate change is appalling. If it was pure ignorance I would be more optimistic about the possibility of mutual understanding and a movement toward adequate response. But it does come down to greed. Shifting from the kind of industry that pollutes our biosphere and promotes everything from coral reef bleaching to the melting of the ice caps is inconvenient to those in power. It is cost ineffective for them to change, and they proceed with a determined bullheadedness that makes me wonder if they care at all for the health and safety of their children and grandchildren. It’s a smash-and-grab approach that continues to do damage to the environment, and it is more chilling than anything I’ve written into my novels. That terrifies me. It also makes me deeply ashamed to be of the same species.”

“I write weird science thrillers for a living and am always jolted when the real world out-weirds what I write. The greed-driven resistance to the overwhelming scientific consensus about climate change is appalling. If it was pure ignorance I would be more optimistic about the possibility of mutual understanding and a movement toward adequate response. But it does come down to greed. Shifting from the kind of industry that pollutes our biosphere and promotes everything from coral reef bleaching to the melting of the ice caps is inconvenient to those in power. It is cost ineffective for them to change, and they proceed with a determined bullheadedness that makes me wonder if they care at all for the health and safety of their children and grandchildren. It’s a smash-and-grab approach that continues to do damage to the environment, and it is more chilling than anything I’ve written into my novels. That terrifies me. It also makes me deeply ashamed to be of the same species.”

Tim Lebbon, author of Relics (a horror novel about wildlife trafficking) and 40 other books:

“The planet’s going to be just fine. It’s not something that people want to hear, but when our time is up and humanity is gone, the planet will move on. It’ll get better, it will be different, and our effect on its history will probably be felt for many millennia to come.

“The planet’s going to be just fine. It’s not something that people want to hear, but when our time is up and humanity is gone, the planet will move on. It’ll get better, it will be different, and our effect on its history will probably be felt for many millennia to come.

“But while we’re still here, the environmental issue that troubles me the most — aside from the obvious ones involving climate change and the imminent disaster we’re facing — is our failure at waste management. Micro-beads (used in facial scrubs, etc.) find their way into the guts of deep sea fish. Islands a thousand miles from anywhere are covered in rubbish swept along on ocean currents. Not only are we drastically affecting our planet’s climate, we’re spoiling it for ourselves and the animals that live upon it, too.

“However, I’m also uplifted by the way nature adapts. There’s a species of cliff swallow that has seen its wingspan reducing by several millimeters over a very short time, because it nests beneath road bridges and a shorter wing span enables it to dodge traffic more effectively. It’s a positive example of evolution at work, and nature adapting to the environments we create.”

Owl Goingback, the Bram Stoker Award-winning author of numerous novels, children’s books, scripts and short stories:

“The environmental issue that scares me the most is the shortage of safe, clean drinking water. It’s a global problem, with over a billion people already lacking access to potable water. And the problem is rapidly growing. Scientists estimate that within the next 10 years, two-thirds of the Earth’s population may face severe water deficits.

“The environmental issue that scares me the most is the shortage of safe, clean drinking water. It’s a global problem, with over a billion people already lacking access to potable water. And the problem is rapidly growing. Scientists estimate that within the next 10 years, two-thirds of the Earth’s population may face severe water deficits.

“Climate changes, pollution and the overuse of existing water tables have put us in a stressed situation. And it’s not just happening in third-world countries. We’ve seen lakes and wetlands here in the United States dry up due to increased water demands.

“In California, and the American Southwest, heavily populated cities have faced off against rural farming communities over ownership and control of existing water supplies. These “water wars” are not new, for such legal battles have been waged since the 19th century, but tensions may escalate over dwindling resources.

“Recent protests by the Standing Rock Sioux, and their supporters, against oil companies routing the Dakota Access Pipeline beneath Lake Oahe (part of the Missouri River), have served to remind us about the importance of drinkable water, and how easily it can be contaminated. As Native Americans say: ‘Water is life.’”

Join the discussion — share your favorite environmental horrors by commenting below, or tag us on Twitter at @Revelator_News.

Related on The Revelator:

The above messages are something the present Administration can’t seem to get a handle on possibly because the ones in charge have always put money first in their decisions with little thought to the natural part of this planet. If this is the case I pity the ones who will have to live in an unsustainable world.

Ther spring will not be silent. It will be drowned out by the roar of blinking LEDs.