On her first visit to the Republic of Chad in 1995, Stephanie Vergniault fell in love with the country’s elephants. Plentiful and easy to see at the time, they gave her a sense of freedom and peace.

That was before the elephant poaching crisis began. By 2007, the elephant numbers had plummeted — from 20,000 in the mid-1990s to roughly 4,000 that year. Today only about 1,200 remain in Chad.

“They were no longer visible,” she recalls. “Poaching was decimating the elephants of Central Africa without anybody reacting.”

That’s when she established SOS Elephants, the first organization in Chad dedicated to saving the elephants.

Vergniault, a native of France, set up camp in southwestern Chad where she could monitor the area’s elephants, then numbering about 300. The area has no protected status, which could help provide funding and additional security, so it is a frequent target of poachers — 63 elephants were slaughtered in July/August 2012, another 86 in a single week in March 2013, and 13 more were gunned down in a March 2017 spree, among other incidents.

Yet without her efforts, the situation would likely be worse. In her earnest and quiet way, she has captured attention of Chadian president Idriss Déby Itno about the elephants’ plight. The species’ protection is now a high priority, and the country’s military is active in responding to poaching incidents. She has also built support for elephants in communities, which has led to a network of informants who will provide information on both elephant movements and poachers.

Elephants, too, tend to see the area as a safer haven, as they often flee there to escape poaching elsewhere. About 500 elephants now inhabit the region.

Living on the front lines, Vergniault feels the elephants’ distress and does everything she can with her limited resources. She spoke with me about her experiences and priorities for elephant conservation in Chad.

Neme: Tell me about the most recent poaching incidents?

Vergniault: It started on 22 March in Bousso. Thirteen elephants were killed and ten were wounded by bullets. The government deployed troops but it was too late.

Even though the elephants were found without their tusks, I suspect that the main motive was to get rid of the elephants within this particular area, where human-elephant conflict is very high. Twenty people were killed the past few years by the elephants, and crops were devastated. I suspect some of the local communities to be accomplices with the poachers.

It was very sad because I could not do much. I was just staying nearby the elephants and trying to protect them and push away the communities.

Neme: How is your work viewed in Chad?

Vergniault: At the beginning, the president looked at my work with a certain level of curiosity. Over time, he became more involved and the protection of elephants has become a national priority.

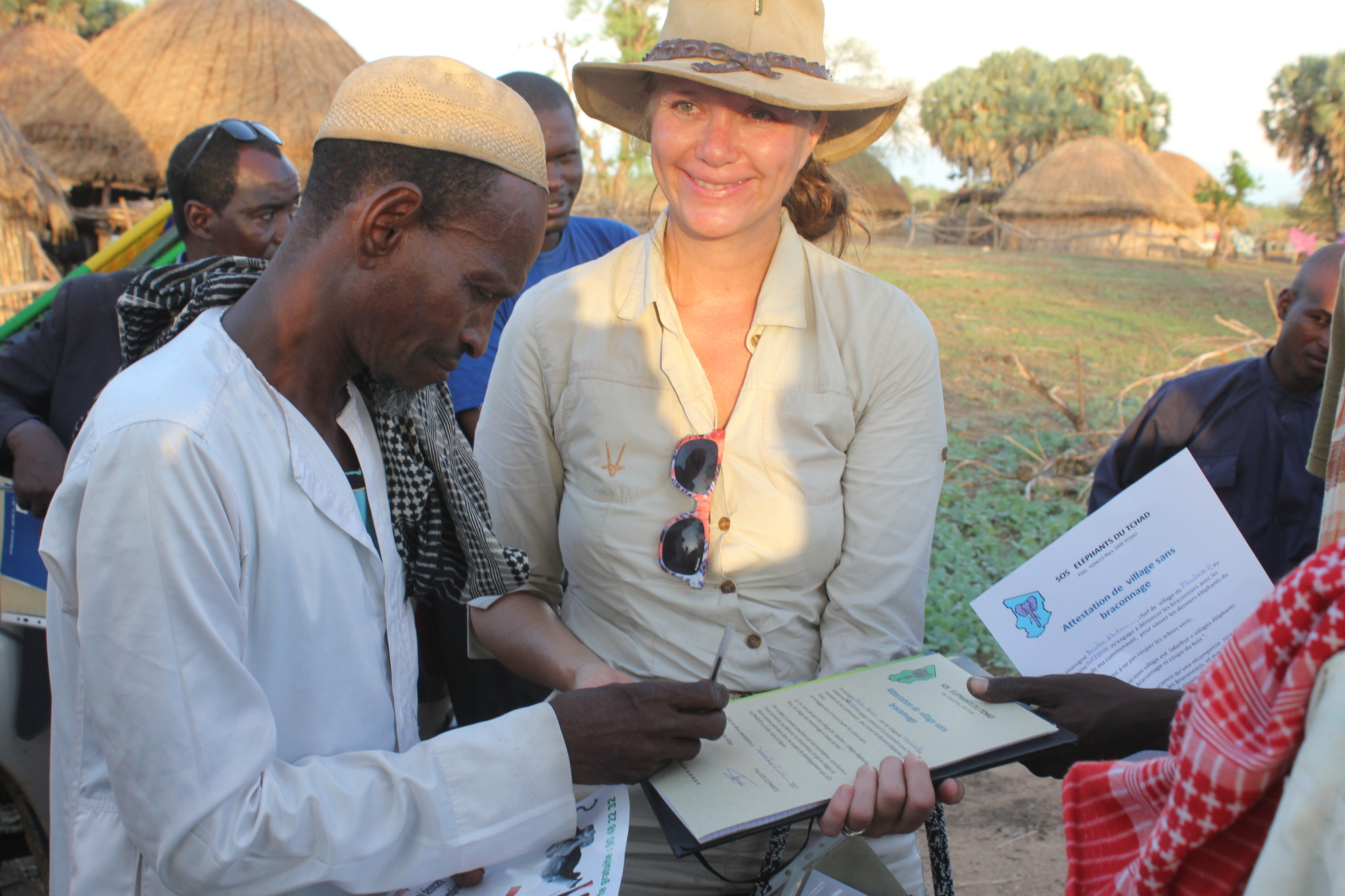

Village people know me and my team and are happy to work with us. They will call our free “green line” to give us information, and we reward them. Over time, we have established a list of people who give us information about the presence of elephants and also about poachers.

But at the same time they would like me to take care of their problem of crops being eaten by the elephants. I ask them to be patient, but they lose patience because of the deteriorating economic situation in the country. [Editor’s note: Chad depends on oil for 70 percent of its income, and plunging oil prices have devastated the country’s economy.]

Neme: What are you doing to change attitudes?

Vergniault: Communities need to feel that you are supporting them and that you understand their situation. Gradually, they become more receptive toward the elephants because we are giving the elephants a lot of attention, and they understand that these elephants can be a potential source of revenue.

One of my favorite programs is the development of beekeeping [to repel elephants and protect crops]. I want to target this activity in the villages that help us protect elephants. Another is an environmental school. So far, at least 500 children have been educated. I think I have given these children a love for elephants, and I hope they continue to fight to save them when I am too old or no longer here.

Neme: What are some of your biggest challenges?

Vergniault: Certain remote villages hesitate to work with us because they are more or less accomplices with the poachers. We try to engage these communities, but it is not simple because they are from semi-nomadic tribes in which hunting is cultural. These villagers are very poor. There is a lack of basic education. They do not send their children to school but send them to keep the cattle in the bush. And the poachers use them as guides to reach the elephants. Last week I went to the bush, a five-hour drive from Ndjamena, with brochures to distribute to them, and promised a big reward to anyone who denounces the poachers.

It remains challenging but we have to engage them. I need to push them to realize how much an elephant alive can benefit their communities.

The situation in Chad is also complicated because of Boko Haram. We were working with a lot of soldiers on anti-poaching, but many were sent to the Lake Chad area to fight against Boko Haram. The last two years, I do not have soldiers to protect my camp. Since November 2016, 30 elephants have been killed in my area.

On top of that, the elephants are destroying farmers’ crops, and because no compensation is given to them, they are more and more hostile to the presence of the elephants.

Neme: What are your hopes for the future?

Vergniault: For more than 10 years I have been calling for the government of Chad to register this area as a protected area. I understand now that I will have to take the lead to make it happen and organize experts to do the feasibility studies and field research.

Lack of resources remains a major challenge. Right now I am using my own money in this battle. I have logistical problems and cannot implement our activities on a larger scale. We also need drones and aircraft to better monitor the area. I need more experts to come and help with anti-poaching, education and eco-tourism training.

Neme: Do you feel you have had an impact?

Vergniault: Some people compare me to Dian Fossey [the famous primatologist who studied mountain gorillas]. I am not sure it is very optimistic because she died alone, killed by a group of poachers.

I am proud that I have influenced the survival of the herds in my area, and that 500 elephants are still here roaming around. It is a success, but it also generates more and more trouble for the farmers. It remains challenging, but I cannot give up.

© Laurel Neme, all rights reserved

Related on The Revelator:

Wildlife/human conflicts like those described here are caused by human overpopulation. Humans and their agriculture & infrastructure are just about everywhere on land that’s inhabitable, and the dominant human attitude is Humans First instead of Earth First. The only real solution to problems like the one described here is a major change in human attitudes toward nature and the natural world. Otherwise, for example, people like Stephanie Vergniault who are heroically fighting poaching will just be playing whack-a-mole.

The Chad govt needs to be engaged by the larger animal welfare groups to provide training to help this lady. She cannot go it alone . Resources need to be met. What is CITES doing? One cannot believe that an international organisation such as this is not getting involved to protect these animals. What is the actual role of CITES ??