Adapted from Four-Fifths a Grizzly: A New Perspective on Nature That Just Might Save Us All © 2021 by Douglas Chadwick. Reprinted with permission by Patagonia.

Around the same time biologists realized that our definitions of nature had been too limited, ecologists began to see that the century-and-a-half-old practice of setting aside reserves here and there to safeguard nature was coming up short. It proved especially mismatched to the needs of big, mobile animals. Elephants, for example, and jaguars, wild camels, wolves, gazelles, bears, lions … name one of the sizeable fellow mammals we find especially compelling and most want to save.

When societies started establishing parks and preserves, much of the countryside around them remained more or less intact and able to provide important habitats at certain times of year and serve as travel routes to other vital habitats. That is no longer the case. Settlement and development have been fragmenting those landscapes, cutting reserves off from neighboring terrain and from each other. Many of the protected natural areas are turning into islands lapped by an ocean of humanity.

In 21st-century settings, animals traveling beyond refuges often struggle to find habitats with adequate food and security in adjoining terrain. Their chances for survival and reproduction there drop faster by the year. Increasingly isolated, the wildlife inside reserves becomes more susceptible to inbreeding and whatever natural disasters sweep through. Now add pressures from a global environment in the throes of a strong and accelerating warming trend. We already know that species on oceanic islands face an elevated risk of extinction. We also know that the smaller an island is and the farther away it lies from other areas with wildlife populations, the less variety of life it is able to support over time.

We owe earlier conservationists our praise for scrambling to save nature by placing intact chunks of it off-limits to most kinds of human disturbance. At the time, it wasn’t clear that separate, scattered tracts could not by themselves fulfill the promise of preserving our natural heritage into the future. Hardly anyone foresaw how crowded and busy the world would soon be. That left present-day conservationists with a problem. But there is a fix for it: connections, the very same quality I’ve been examining throughout this book as the essence of living systems large and small.

If you want to see connectivity being built into a region’s landscapes, you could grab a backpack and do some roaming of your own along the backbone of North America. There, you’ll find the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (or Y2Y, as both the region and the organization are nicknamed) at work. Its goal is to conserve the 2,000-mile segment of the Continental Divide ecoregion that stretches from Wyoming’s Wind River Range to the headwaters of the Peel River in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

Audacious? By past standards, definitely. In terms of what we know about conservation now? It’s what’s called for.

Look at the heritage at stake: half a million square miles of spectacular topography holding scores of reserves — among them, the world- renowned national parks of Grand Teton, Yellowstone, Glacier, Waterton Lakes, Banff, and Jasper. Y2Y is one of the very few large landscapes in a temperate climate zone that still has all of its native species. They include the greatest variety of wild plants in Canada and the highest diversity of big wild animals in North America. Not only have there been no extinctions recorded here, nearly all the region’s flora and fauna are doing reasonably well, which is unusual anywhere on the globe nowadays.

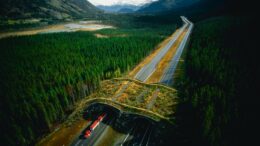

Recognized wildland strongholds with prime habitats and unspoiled scenery form the cores, or focal areas, in Y2Y’s design for regional conservation. Gaining protection for some of the biologically richest spots not already safeguarded as parks or preserves is part of the plan. The second part is securing connections — variously called linkage zones, habitat bridges, wildlife corridors, passageways, or just wildways — from one stronghold to the next, ideally through the least disturbed places left in between. The final part of Y2Y’s mission embraces a necessary third dimension of connectivity in the Anthropocene: trying to blend conservation needs with the interests of local human communities.

The Initiative has more than 218 current partners in the United States and Canada. They include businesses, private landowners, Native American groups, scientists, resource institutes, and environmental organizations. It will take a coalition of this breadth to assemble a network of cores and varied connections that collectively operate as a meta-reserve across portions of two territories and two provinces in Canada and five U.S. states. If this vision becomes a reality, the entire ecoregion could continue to function at nearly full strength as a natural system. Indefinitely. And if the network only gets partially completed, that may still be enough to keep the natural realm from having to keep giving way, again and again, until the remnants stand huddled in refuges where people go to see what used to run far, wide, and free.

In 1993, the year the Y2Y coalition was formally launched, its ambitions were viewed by some as pie-in-the-sky-class unrealistic and by others as a grave threat to the economy. Protected core areas made up 10 to 11% of the ecoregion at the time. A quarter of a century later, that figure has more than doubled. Some of the added acreage consists of new national parks and wilderness areas. Recently established buffer zones, special management areas, recreation areas, natural areas, ecological reserves, state and provincial parks, and similar administrative units within Y2Y’s vast stockpile of public lands also count toward the core areas total.

Although few of these other segments are as strictly protected as a national park, the regulations governing them still provide an improved level of security for the native flora and fauna. The same holds true for various portions of public land given enough safeguards against unchecked development to help tie the core areas to one another. Land trusts contributed still more linkage acreage by arranging conservation easements with the owners of private properties. According to Y2Y’s analysis, total connectivity along the length of the Yellowstone to Yukon landscape increased from 5 percent in 1993 to more than 30 percent today.

Negotiations are underway to begin setting up Indigenous Protective Areas on treaty lands in Canada claimed by First Nations people. Since the Protective Areas are to be managed by the tribes to conserve traditional natural resources, they may soon add tremendous amounts of territory with improved management of the region’s living resources.

Now I understand what the Initiative’s first coordinator, Bart Robinson, meant when I asked him in the early 1990s what Y2Y was actually doing besides announcing worthy intentions, and he replied, “We’re in year two of a 100-year plan.” He was telling me that a conservation effort at this whopping scale necessarily starts with wishful thinking. The Initiative did a lot of that in its early years and still does. Willful optimism, steadily supplied, can be contagious. It has already helped make Y2Y one of the best-conserved mountain ecosystems in the world, and we’re still only in year 28 as of 2021.

Another important transformation was taking place in much of the ecoregion during the same period. Recreation and tourism became major generators of jobs and revenue. The long-standing ideology that more protection for the environment hurts business started going the way of typewriters and rotary dial telephones as environmental progress and economic progress kept advancing arm in arm through districts from northern Wyoming well into British Columbia and Alberta. Figures from the Outdoor Industry Association recently showed outdoor recreation in Montana surpassing agriculture to emerge as the largest, most dynamic sector of the state’s economy.

People like the phrase “Build it, and they will come.” Here, though, the planet built the main attractions — the towering scenery, mountain-fresh air and water, plentiful wildlife, and other natural features that economists speak of as amenities. We need only to sustain them. The role of conservation as a strong stimulant to businesses is becoming a social and political game-changer.

Residents of the Mountain West had grown accustomed to picking sides in the seemingly endless polarizing arguments between pro-industry representatives and conservationists, each camp labeling the other as the enemy of a brighter future. These days, more politicians and voters are looking toward the middle, intrigued by planning efforts that enlist a wide range of interest groups.

Cooperative decision-making certainly sounds good. In practice, finding common ground on environmental issues qualifies as one of the hardest challenges disparate groups can take on when they are more used to condemning opponents than listening to them. Can humans and wildlife truly prosper together over time? Of course they could.

The underlying issue has always been whether people with different backgrounds and interests can work well enough with one another to make a better level of coexistence with nature possible. In a way, Y2Y is an experiment to find out how much better that level could be.

© 2021 by Douglas Chadwick. Reprinted with permission by Patagonia.