Nimbus, a wolverine we had GPS-collared, kept drawing an intriguing pattern on our map. For weeks, he returned again and again to one site — spending four hours there one day, nine the next. I thought, surely, he’d found a carcass. Caribou maybe, or even muskox. I couldn’t imagine what else it could be.

So my colleague Louise Bishop and I found time to investigate.

We’d come to Arctic Alaska to study how these curious critters use permafrost and had spent weeks during this unusually cold winter visiting places where they spend time. We had yet to visit Nimbus’s favorite site, so we skimmed north by snowmachine as April’s high sun flooded the tundra around us.

Wolverines usually spent just a few hours at the places we visited, leaving slick bowls formed when they slept, often tucked at the end of snow tunnels. Sometimes we found scat nearby, or ptarmigan remains. Though the region teems with caribou during summer, none were there now. Maybe one got lost, I thought.

Nimbus’s site was on the Shaviovik River, between the Prudhoe oilfields and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. When we were a mile away, we descended 20 abrupt feet to the river’s floodplain, then picked our way through willows and sharp snowdrifts, homing in.

The GPS data came unambiguously from a single 60-yard stretch of river. When we arrived, there was nothing. No carcass, no bowl, no scat. The river channel was frozen, though some ice seemed recently formed. Wolverine tracks loped along the bank.

Nimbus’s data pointed to the channel’s center, but we were reluctant to venture onto questionably stable ice. Anyway, what could be out there — just 10 yards away — that we couldn’t see from shore?

Exploring the area, Louise turned up the first wolverine scat. We prodded it gently, and tiny glimmering discs fell onto the snow. I looked up, incredulous. “Are those fish scales?”

Wolverine is Gulo gulo; the glutton so nice they named it twice. Across their range, they are known to eat goats, grouse, goose eggs and everything between. People have been picking apart their scat for half a century. I had never heard of anyone finding fish scales.

So we were delighted, but also disappointed. The channel was frozen, the feast apparently over. Was this wolverine swimming during Arctic winter? Or had he gotten fish some other way?

In the coming days, to my amazement, Nimbus marched back to the channel and sat at its center for hours, accumulating GPS locations at a baffling rate. From camp, I inspected our photos of the barren ice, imagining him there. What on earth was he doing?

So, we returned, determined to stand at Nimbus’s exact location. At the site, I gingerly stepped onto the frozen river and chipped a hole with an ax. No water after six inches, so I proceeded slowly, cutting new holes every few feet.

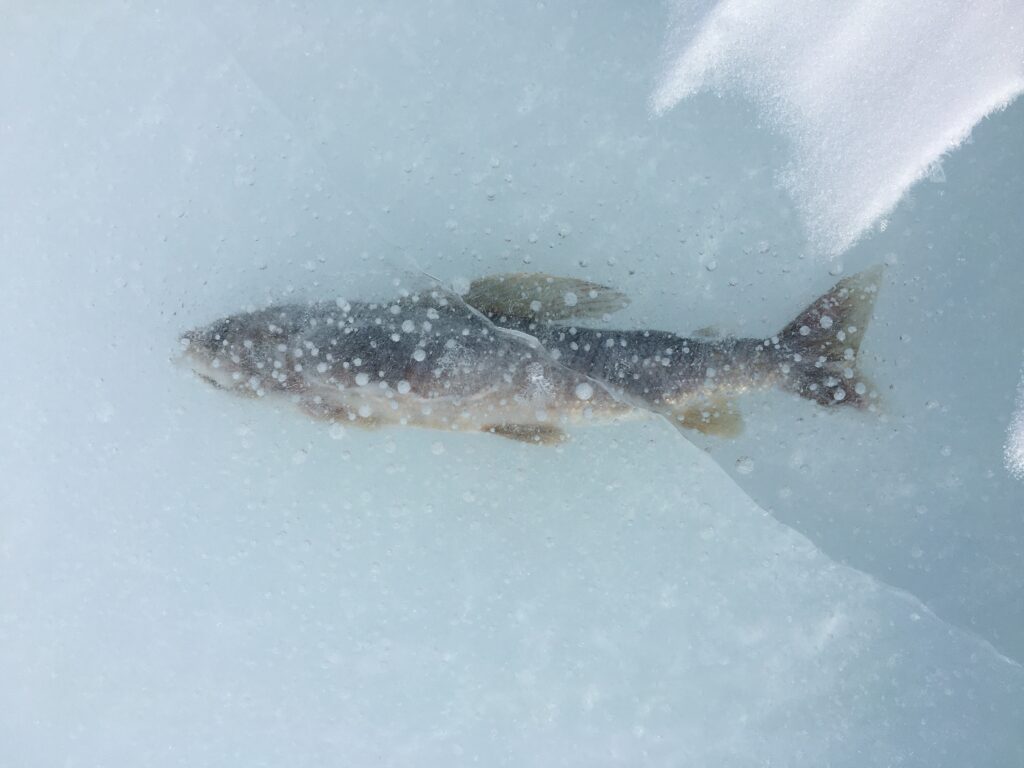

At the channel center, I swung the ax and felt it break through a thin top layer, then sink into something soft. I leaned in to inspect. “Hah!” I yelled. “I got a fish!” It was frozen, entombed in the ice just under its surface.

We eventually found nearly 100 fish in the channel. Many were in the ice that had seemed newly formed from shore, and under them lay a foot of unfrozen water. Others, though, were spread far downstream, apparently carried there when the ice ruptured and water gushed onto the surface. Nimbus had been clawing and gnawing, excavating them one by one, leaving a trail of fish-shaped holes. A bevy of other scavengers — arctic fox, red fox and ravens — were close behind, cleaning up.

Finding water was a surprise, since it’s rare up here this time of year. Rivers freeze solid from October to May, and lakes shrink to puddles under ice as thick as your car. It’s a hard time to be a fish. But there are a few springs where waters spout forth year-round and provide overwintering habitat. Perhaps, I thought, this is such a site.

My hunch was later confirmed. Old reports we found mentioned thousands of fish preparing to overwinter here in autumn, and we learned that it’s known to the local Iñupiat, who harvest these fish for food, as the “Place Where the Land Sweats.”

But our observation held an element of newness. Oases like this give freshwater fish a lifeline through the harsh Arctic winter, but knowledge about mortality — let alone a mass die-off like this — remains scarce. How often do these oases become traps? With weather becoming more extreme due to climate change, could it happen more often — or less often? Could that pose a problem for all the species that depend on this river?

This morbid find, equally fascinating and disturbing (and described in our recent Ecology paper), connected seemingly distant corners of the ecosystem — fish, ice, wolverine, people — and reminded us that even little things, like a slow spring or a cold winter, can tip the balance.

It was bad news for the fish, no doubt, but I keep thinking of Nimbus, the first wolverine recorded eating fish. It brings a smile to imagine him out there, trotting along the Shaviovik after a long, cold winter, sun warming his back as he lifts his snout to the breeze and absorbs that first, bountiful whiff.

Previously in The Revelator:

Road to Nowhere: Highways Pose Existential Threat to Wolverines