August is normally Arizona’s wettest month.

Not this year, though. The usual monsoon season failed to arrive, and just 1.5 inches of rain fell sporadically on the state throughout the month — the same period that the city of Phoenix experienced record high temperatures of up to 114 degrees Fahrenheit.

The soaring temperatures and specter of drought have left many Arizona residents worrying about their access to water.

It’s also driven wildlife managers to fret over whether the state’s abundant wildlife — which rely on infrequent rains — will have enough water to survive.

“As the drought has deepened, the waters that wildlife traditionally used are going away or have completely disappeared,” says Kevin Woolridge, a teacher at Blue Ridge High School in Arizona who, with his students’ help, has collaborated with the Arizona Game and Fish Department to monitor the drought and its impact on wildlife.

Meanwhile a new manmade threat to Arizona’s water has cropped up. The Trump administration has begun construction on a stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border wall at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a UNESCO biosphere reserve. As part of construction, the Trump administration plans to pull up some of Arizona’s precious groundwater — not to hydrate people or animals, but to mix with concrete to build a 44-mile section of the border wall.

While the federal government spends billions on its wall across the border and sucks up some of Arizona’s last remaining ancient groundwater in the process, Arizona wildlife officials are asking the public for millions of dollars in donations to fund the delivery of water to animals in parched areas across the state.

A History of Water Capture Turns to Delivery

Beginning in the 1940s, long before the world was aware of climate change, ranchers in Arizona made the arid landscape more hospitable to their cattle by building concrete rain catchments.

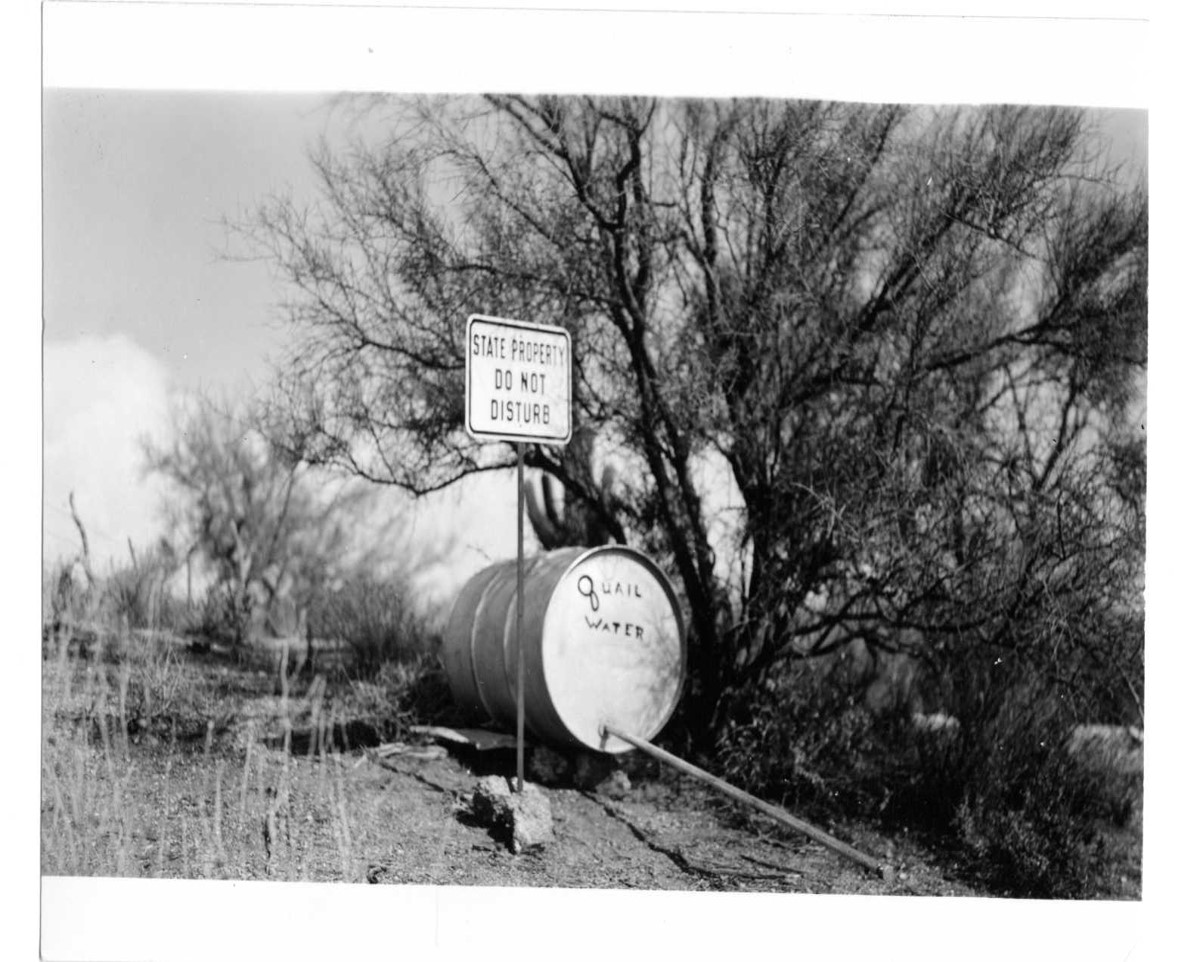

At the same time, Arizona wildlife officials began doing the same thing to provide supplemental water to game birds such as quail and dove. When they noticed that all kinds of wildlife — including insects —were also drinking from catchments, they built more. In total 3,000 units for all species have been constructed across the state.

For decades rainwater was enough to fill the catchments regularly. But as the global climate has continued to warm, Arizona fell into a long-term drought, and many catchments are now dry. With natural water sources also drying up, and animals going thirsty, officials with the Arizona Game and Fish Department have resorted to trucking out water to fill these catchments at a rate of 1.5 million gallons annually. They rely on donations from the public to keep the $1 million-a-year water deliveries going.

Experts say humans are the clear culprits for this water loss and need for water delivery.

“It’s hard not to see the effect of urban development on natural streams in Arizona,” says Hector Zamora of the University of Arizona, who has studied watersheds in southern Arizona. “Rivers that used to freely flow in the 1900s — such as the Gila River, the Sonoyta River and the Santa Cruz River — are now bone dry. Climate change will likely further degrade these already stressed systems.”

And Arizona is not alone. Similar situations are playing out around the country and the world. Wildlife officials are trucking in water to animals in southern Nevada, where the Bureau of Land Management has had to deliver water to feral horses in order to prevent their certain death. Water deliveries to wildlife are becoming more common in fast-warming areas, such as southern Australia, where without aid the country’s iconic koalas would die of dehydration, and in Kenya where elephants have also been spared by truckloads of water.

Across the world wildlife officials say rivers are drying up, and they are increasingly being forced to transport water to wildlife by truck and monitor catchments by helicopter, two costly and carbon-intensive modes of transport.

“My assumption is that burning fossil fuels to deliver the water to the catchment areas is impacting and exacerbating the overall situation,” says Woolridge, who is overseeing a catchment-sensor project developed by one of his students that could make it easier for Arizona to monitor water levels. “However, the cost of doing nothing is potentially catastrophic.”

Joseph Currie, habitat-planning program manager for the Arizona Game and Fish Department, agrees. “At present there is no relief in sight from the drought conditions and reduction in free surface water.”

It’s not a stretch to think humans might be next: According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, population growth, increased development and intensifying climate changes will lead to “greater water demand in growing cities and reduced water availability could also affect [residents’] access to drinking water” throughout Arizona and the Southwest.

The Wall: Making Things Worse

Arizona Public Media reports that the U.S. Customs and Border Protection estimates building along Organ Pipes Cactus National Monument will require at least 84,000 gallons of water per day pumped from the ground around Quitobaquito Springs and other natural water sources along the border.

Such springs are uncommon, according to Zamora, who adds that besides serving as important sources of water to wildlife, they are also culturally important.

“Quitobaquito Springs has been visited since prehistoric times by Native Americans and is considered sacred by the Tohono O’odham Nation,” he says. They were also visited by missionaries and the Forty-Niners during California’s Gold Rush.

Ancient waters feed the springs, meaning that they’re not currently being recharged, says Zamora. Once the water’s gone, it’s gone.

Working for Solutions

With waters around Arizona drying up, Currie is leading a long-term project updating existing water catchments across the state with troughs and tanks that are more smartly designed and placed.

One way he’s boosted the catchments’ design efficiency is to increase the size of the rainwater collection aprons, allowing for more rain to be caught and less to evaporate, and spacing catchments at least two miles apart — increasing the availability of water to a larger number of wildlife.

But replacing catchments is a slow process. The department is currently on track to replace just 20 a year. At that rate it would take 150 years to upgrade the entire system.

Historically the use of catchments to provide water for wildlife has been a controversial subject because of their potential to stagnate and spread disease, and possibly lead to deadly predator-prey interactions where water is made available. However, a small but growing body of recent research — including in California’s Mojave Desert — suggests that presence of manmade water catchments appears to increase biodiversity more than natural precipitation.

While the scientific consensus on water catchments is currently unsettled, Currie says he’s observed what appear to be positive effects of providing water for wildlife. Water catchments in Arizona bring a resurgence of mule deer, javelin, quail and other species in former ranching areas where they’d disappeared, he says. His team monitors catchments with trail cameras, which reveal that virtually every native species in Arizona — from chipmunks to eagles to elk — does indeed drink from troughs across the state.

He adds that building well-planned water catchments can make it possible “to better distribute wildlife in usable habitat so that certain areas are not over grazed by wildlife,” helping preserve the integrity of Arizona’s wild landscape. In his 22 years working with water catchments, Currie says the spread of disease hasn’t been a problem, and water quality in Arizona Game and Fish Department’s catchments remains high.

While Arizona’s water catchments and deliveries may help keep wildlife hydrated, a better strategy — not just in the state but worldwide — would be to more intelligently plan water use, says Benjamin I. Cook, climate expert at NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“It’s less about humans needing to proactively provide water for wildlife and ecosystems,” he says, “and more about managing human water withdrawals and water consumption so that enough is left for natural systems.”

As for the situation at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, sucking out Arizona’s natural groundwater to build the border wall, Zamora says, is probably an unwise use of water that will leave Arizona’s fauna — including its people — high and dry.

![]()