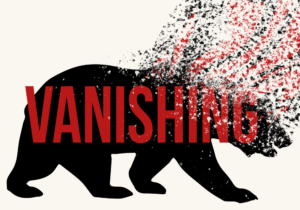

What happens to us as the wild world unravels? Vanishing, an occasional essay series, explores some of the human stakes of the wildlife extinction crisis.

Years ago, a long season of chemotherapy left me unable to hear high frequencies. How does one comprehend what one’s not hearing? I didn’t know.

The recovery kept me out of the mountains for a long time. But finally a grand day came: My partner and I hiked up into the talus slopes of the North Cascades in Washington state. Mount Baker stood before us and Mount Shuksan at our backs — a day of perfect heaven. Suddenly his face lit up: “Hear that? Eeeeep!” I strained my ears to listen and heard nothing. “You don’t hear that?” he cried in dismay. I felt divorced, absented from something that, even when I was far away, had made my world feel whole and alive.

The recovery kept me out of the mountains for a long time. But finally a grand day came: My partner and I hiked up into the talus slopes of the North Cascades in Washington state. Mount Baker stood before us and Mount Shuksan at our backs — a day of perfect heaven. Suddenly his face lit up: “Hear that? Eeeeep!” I strained my ears to listen and heard nothing. “You don’t hear that?” he cried in dismay. I felt divorced, absented from something that, even when I was far away, had made my world feel whole and alive.

Without the familiar sound of American pikas, I could see the mountain, but I couldn’t feel it, couldn’t sense the pulse of the mountain underfoot or its voice echoing across the rocks. It wasn’t home anymore; it was just scenery.

This premonition of their absence made me feel how much I would miss pikas if they disappeared, because when you hear them, you know you’ve arrived at a place not our own.

First there must be an ascent, perhaps from a lowland parking lot, a long climb from a roiling riverbed through close-trunked moss to widening skies; perhaps away from a trailhead bulldozed out of some mountain pass or high meadow. You must rise into those places where the horizon leans, where the earth falls away yet towers above, where the forests thin to clumps then draw tight into krummholzen sculpted by wind and snow, where lowland greens contract to heather slopes. You must crouch to taste the blueberries and step carefully through fairy gardens — lupine, paintbrush, bistort, hellebore and monkeyflower — until finally you round a rocky point and hear them: a high shrill whistle from somewhere, you can’t say just where, echoing across the slopes.

Eeeeep! You stop, and look. Where? It repeats — EEEEEEP!! — thin, tense, urgent. A flick at the edge of vision, and there she is, watching you. Alert as a hawk. Pika. “Pie-ka” we say today, but as it used to be pronounced, “pee-ka.” Peeeeeee-ka!

You have arrived. This is not your home, nor should it be. But it is theirs, and they’ve seen you, and put their whole world on alert: Watch out! It may be okay this time, but it may not. Humans. Perhaps a dog. You never know. Eeeee-ka!

The pika’s world intersects with ours only when we want it to, for it is we who visit them, never the other way around. I will never step out my door and spook a pika from my yard. And we visit them only in summers, for us a time to play — “recreation” we call it, or re-creation — but for them a time to work.

All pika futurity is at stake every summer, for the few weeks between the last snowmelt and the first snowfall are for them the pinch of the hourglass. If they make it through this season well, there will be another pika summer. But only if.

Worse, our world intersects with theirs even when we’re not intruding on their slopes. Pikas, adapted so well to alpine cold, cannot endure lowland heat. Above 78 degrees F., they must take shelter or move upslope to cooler air. As global warming intensifies, fears have grown for pika futures; while they can move up the mountain as temperatures rise, at some point they will run out of mountain. This has indeed been the fate of some low-elevation populations. Too many intrusions from us, too many curious dogs in tow, too many of our greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere we share, and our highland summer recreations will be a lot lonelier.

We’ll have, as we like to say, the whole place to ourselves.

Pikas fool us with their insane cuteness. They look like baby rabbits with lopped ears, no tails, and hardly any legs, for everything that could radiate heat has been trimmed and tucked in. Except for their eyes, which are large and alert and miss nothing. They look like rodents but aren’t. Their closest relatives are indeed rabbits, but unlike the floppy loners that casually nibble our backyard flowers, pikas are sociable. The one you’re looking at, who is looking at you, has just alerted the whole village, and her neighbors are on pause, scanning the airwaves.

Their village is hidden underground, knitted amidst the cracks and crannies sheltered by rocks that will twist your ankle if you tread them but are rock-solid to them, every turn and cavity mapped out in pika mind. They don’t hibernate but munch and scurry through the long winter under the mountain’s carapace of snow. The pika watching you — Ah! She’s just chuckled another signal and flickered away out of sight — spotted you because she left her shelter to venture after her food: alpine flowers, cut and gathered into haystacks curing on the sunbaked rocks. She’ll turn her haystacks as they cure and when they’re ready she’ll carry them by mouthfuls safe underground. While her back is turned, gathering more, some freeloading neighbor might filch a mouthful for their own provision. All winter long the village will live on summer sun, stored away under the snows.

Pika cuteness masks tough little souls. While researchers have documented pika declines, they have also documented remarkable resilience: So far, populations in many areas, including the North Cascades, are holding steady. As daytime temperatures spike, they adapt, sheltering in the rocks and foraging by night. Yet were pikas to become nocturnal, pika slopes would appear silent to human visitors, who can only climb safely by daylight. They might still be there, but not for us.

I felt that silence on my trip to Mount Baker years ago, a day when the life of the mountain seemed somehow smaller and poorer for their absence.

Years later, there was another such day. This time I had brand new hearing aids, a technological miracle. The sky was clear, the blueberries just turning sweet, the heady scent of lupine and the mountain like an angel rising before us —and Eeeeep!

I was again in pika country. This time I heard her. Not just the small bundle of energy eyeing us from below the trail, but the great volume of air she filled with a voice not our own, in a world not our own, a world of other voices and other urgencies that ask us for nothing more than to be left to their own ways.

We have yet to learn what Aldo Leopold taught us over 70 years ago, that mountains are fountains of energy. Pikas are distillations of mountain energy, trimmed down to bright sparks of life, declaring for nations beyond ours. Pikas are mountain thoughts, sparks of thought burning bright, arks that carry that light through the dark. Not until we hear what they are telling us will we have arrived.

Explore the rest of the Vanishing series and discuss these and other #VanishingSpecies on Twitter.

![]()