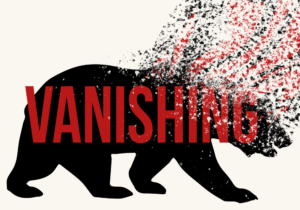

What happens to us as the wild world unravels? Vanishing, an occasional essay series, explores some of the human stakes of the wildlife extinction crisis.

There is a frozen sea inside me. Inside all of us. Franz Kafka wrote in a letter in 1904 that a book should shatter our ice-choked inland seas — and as a lover of books and the ways they engineer empathies, I wouldn’t disagree. But it’s loving hummingbirds and contemplating their leaving that has broken me apart recently.

A 2019 study of bird declines in North America told a heartbreaking story about hummingbirds: There are 18 million fewer of them now than there were in 1970.

A 2019 study of bird declines in North America told a heartbreaking story about hummingbirds: There are 18 million fewer of them now than there were in 1970.

Just imagining the absence of hummingbirds sent me to bed for the day, sick with grief.

Enter the icepick beak of the hummingbird. Some species have beaks that have evolved expressly for waging tiny wars, gladiators among the gladioluses. For picking, pinching, poking, lancing and dancing — all to defend precious food sources and duel for mates. And, apparently, to puncture my heart.

Pick, pick. Yours is not a tolerable extinction. (As if any of them ever are.) Pierce, pierce. Trochilidae is the name on your family crest, my dear hummingbirds, my familiars. I could not bear for your bough to be chopped off our family tree.

On Facebook I post, but cannot afford to read, an article about mourning rites for glaciers. I have no idea what similar rites for hummingbirds would look like. Or maybe I do.

Maybe it starts when you interrupt that grim parade of would-be extinctions filing past and say to the Juan Fernández firecrown, No, not you.

Unacceptable, glittering starfrontlet.

I won’t live without you in the world, turquoise-throated puffleg.

Maybe it begins when your blanched interior is once again dyed with feeling, sensation returning to fingertips. With these hands I clean and refill my two glass hummingbird feeders like a devotion, to keep mold and bacteria at bay. Poorly maintained feeders can be fatal for my familiars, so even on days when I can maintain no other ritual, I make sure the sugar water is fresh and twinkling in the sun.

Years ago, when living alone and unwell in the rural Southwest, I was told by my landlord, “I knew you were sick when I saw the empty feeders.” You don’t have to know me well — my landlord certainly didn’t — to know that when I’m not feeding hummingbirds, I, too, am lacking nectar. In fact, I identify with these curio-creatures because they, like me, need constant sweetness to survive. They teach me that it is not weakness to require the scandal of red, the saturated and sugared things.

Every spring my wife hangs baskets of mandevilla (we affectionately call them “Mandy”) amid the other hummingbird-seducing flowers, and it is a joy to watch my feathered cousins hover and drink. This is what I call our “pollinator playspace,” a temporary and tenuous refuge for two Black women, hummingbirds, butterflies, and bees — all of us under threat.

In 1904 one warm-blooded mammal wrote to another: “We need books [and hummingbirds] that affect us like a disaster.” A disaster: If, one spring, hummingbirds didn’t return to me. It would be as if all the libraries in the world were shuttered, never to flutter open again.

Explore the rest of the Vanishing series and discuss these and other #VanishingSpecies on Twitter.

![]()