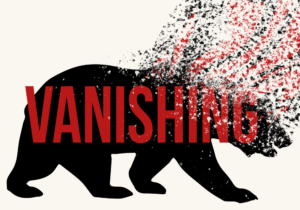

What happens to us as the wild world unravels? Vanishing, an occasional essay series, explores some of the human stakes of the wildlife extinction crisis.

Our small family knew bobolinks from a bird refuge four hours away. Each spring my partner and I made the trip to Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge with our daughter in hopes of seeing the 90-plus species of migratory birds we typically spotted over the course of a binoculared weekend. As we headed West we anticipated the winnowing, sky-dance displays of Wilson’s snipe, the oranges of Bullock’s oriole flashing high in the cottonwoods, and the bright spots of sunshine that dart through riparian thickets — the yellow warbler.

But the bobolink was like a sentinel, the first to greet us each year.

When we found the bobolink’s tuxedoed back and rambling song rising from the fields alongside the dirt road leading to our campground, we knew we’d arrived just where we should be — and right on time. This moment marked not merely the end of our drive but also the bobolink’s astounding feat of flying over 12,000 miles since we’d last heard his call. Bobolinks, who tend to be seen singly, attested to the braiding of wings and land and sea, to the astonishing rhythm of spring’s abundances, and to the persistent migrations of birds, songs and birders.

When we found the bobolink’s tuxedoed back and rambling song rising from the fields alongside the dirt road leading to our campground, we knew we’d arrived just where we should be — and right on time. This moment marked not merely the end of our drive but also the bobolink’s astounding feat of flying over 12,000 miles since we’d last heard his call. Bobolinks, who tend to be seen singly, attested to the braiding of wings and land and sea, to the astonishing rhythm of spring’s abundances, and to the persistent migrations of birds, songs and birders.

One year, just after a bobolink greeted us, we pitched camp at dusk beneath the cliff where hundreds of nesting cliff swallows performed their evening skyward wheelings. As our 5-year-old daughter worked, her little arms pounding tent stakes, she began to sing for the bobolink. Inspired by the bird’s flitting from grassy perch to golden ground, by his piccolo song, we three found ourselves crafting a round.

You know rounds, those woven songs — three layered voices, each joining a line or two after the last until a trio of distinct melodies harmonizes in circling chords. The round ends in a perfect reversal of its beginning, the first voice departing the plaited strain, then the next, until final notes resolve into silence. Early in life, our daughter learned to hold her part as we sang rounds in the car, on the trail, paddling the canoe. We sang popular ones like “Dona Nobis Pachem,” the elegiac notes of that repeated phrase evocative of a wood thrush fluting in pine forest: Give us peace, give us peace, give us peace. Other times, we made up the songs.

That night at the refuge, tent secured, we practiced new harmonies as the sun set in bronze browns over the distant squawks and trumpeting of sandhill cranes. Our completed round rang staccato notes rising and falling, like the bird’s twinkling call (Allegro!):

Bobolink-link-link-link-link-link-link,

Bobolink-link-link-link-link-link-link,

You will miss Bobolink if you blink.

Bobolink, you make me think!

Bobolink made us think because we worked hard to find the bird as we drove into camp. Each breeding male requires a broad territory of tall-grass meadow, so we scanned a wide swath for yellow-backed head, black chest, black-and-white back. We surveyed fence posts and the heads of tall grasses. We rolled down the windows, batting back mosquitoes, hoping bobolink’s chattering call might draw our ears and then our eyes. We had to pay attention.

In the years that followed, our bobolink round became a ritual we performed while setting up camp, celebrating his sentinel welcome and garrulous song. But then one year our song went unsung, our round vanishing with the bird.

We didn’t see bobolinks that spring. Or the next. Maybe our timing was off, we thought. Most likely bobolinks were absent from those fields because they were suffering, their status “declining.” During my lifetime alone, the global population of bobolinks has fallen by more than 65% — this according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which includes bobolinks in a list of species “most at risk of extinction without significant conservation actions.” So we sat in silence at the campground, our daughter wondering how a song no longer suited its own habitat.

Sure, we could sing other rounds, like the one made up of the words for numbers, each numeral corresponding to a note of the scale, complex in its dissonance but perfect for distracting little legs tired from hiking on mountain trails. Or growing girls mourning missing birds in quiet fields. There’s also the funny round her dad made up, something about magpies sitting on fenceposts until they eat animal roadkill. (“Yuck, Dada,” our daughter says before she joins in, too.) Yes, our daughter knows about nature red in tooth and claw, or beak and talon. She knows, too, about species death — that passenger pigeons, for example, were driven extinct across generations, disappearing entirely in the course of someone’s childhood-still-in-progress.

In recent years the bobolinks have returned to the refuge fields. A wildlife biologist reports that their numbers are actually increasing there, but both she and I know better than to give up our concern, because the birds’ presence at this one protected location belies their globally diminishing numbers. Without the deliberate preservation of more prairies, fields and meadows, without changes to the frequency of agricultural mowing across wide swaths of land, bobolinks may die off entirely.

Our daughter, now a teen prone to raising her eyebrows when we start singing rounds and to issuing occasional dramatic outbursts, says, “Nature is dying!” But her sentiment isn’t just teenage angst. How can I express to her my grief over the very real possibility that her melodies will soon have no referents in the landscapes that inspired them? Will she become so accustomed to forms of life falling away that she thinks living means witnessing countless losses due only to human disregard? If so, how can she possibly feel safe loving her world? How can she feel safe loving anything?

For now, she knows two types of bobolink song. I hear them too sometimes, wafting from the occasional bird in the fields or from the reluctant lips of our teenager, who’s thriving and becoming more complex. Unlike her earth.

I find myself mixing notes and phrases in my head, straining to make verses that fit her world, old refrains merging with new into a song more requiem than round:

Give her peace, give birds peace, make us think.

We will miss bobolink if we blink.

Explore the rest of the Vanishing series and discuss these and other #VanishingSpecies on Twitter.

![]()