As heat wave after heat wave scorches the West this summer, it may feel like there’s no escape from the record-breaking temperatures. But mounting research shows one way to help beat the heat: Urban communities with more tree cover fare much better than those that lack a green canopy.

This lack of “tree equity” strongly correlates with race and income. A study of more than 3,000 communities across the United States determined that poor communities with a majority of people of color tend to have less green infrastructure and fewer trees than well-to-do, white areas.

That disparity can be deadly. Heatwaves kill more people than any other natural disaster — some 12,000 a year in the United States. That number is likely to climb as climate change increases the frequency and severity of heat waves.

Los Angeles is among the cities identified as having glaring inequities in green cover for communities of color. But a new project, the USC Urban Trees Initiative, could help cool things off. The project combines advanced mapping technology, air quality research, and landscape architecture, to show the best places to plant new trees. So far it’s been put to use in two neighborhoods that lack shade, with more to follow.

The Revelator spoke to one of the initiative’s researchers — geographer John P. Wilson, a professor at the University of Southern California and director of the Spatial Sciences Institute — about how a city known as the “car capital” could instead be a leader in trees.

How did this research come about?

There’s a story in this month’s National Geographic that makes the case that you need trees if you’re going to combat climate change and you need trees if you’re going to address equity. And I think that both of those things have motivated our desire to work in this space.

Cities are not well positioned to cope with the [rising] heat. How could you mitigate those heat impacts? Obviously one option is to build more controlled indoor environments and increase the amount of air conditioning. But [from an energy and climate standpoint], that’s problematic.

A simple solution would be to have a larger and more sustainable [urban] forest.

Last summer in Los Angeles we had two weeks where the temperature every day was in the 100s. On one of those days a colleague of mine went out with a handheld thermometer. The official temperature that day was 103 F and in the middle of the street the temperature at body height was about 135 F. And then if you walked to the sidewalk and stood underneath a mature tree with a large canopy, then the temperature was in the high 80s, low 90s.

Here in Los Angeles under the leadership of Mayor Eric Garcetti there’s a sustainability plan that includes planting 90,000 trees with an eye to looking at the parts of the city that have the least tree cover now.

The goal of the effort would be increasing tree canopy by 50%, because canopies are going to provide shade, transpiration, muffling or abatement of noise, and support more wildlife. It also has the capacity to take air pollution out of the atmosphere. And of course, at the end of the day, a large forest could help sequester carbon.

There’s a series of commentators, particularly in Europe, who have argued that given all that’s happened or not happened in the last 20-30 years, we actually need carbon negative cities, not carbon neutral cities now.

How are you seeing these climate impacts in Los Angeles?

The benefit of living along the coast in Los Angeles is that you have the sea breeze every day and a land breeze at night. Nature sort of provides air conditioning for free. That was until the real estate agents realized that was the case, and now you need $6 or $10 million to buy a house in those locales.

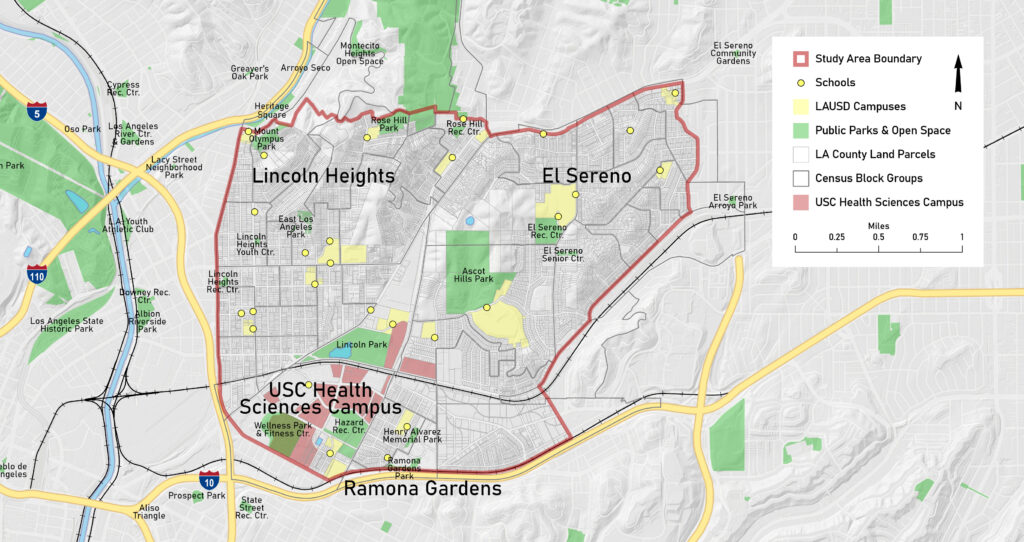

As a consequence most people live between 10 to 50 miles inland. In our study neighborhoods of El Soreno and Lincoln Heights, research indicates that in the last 20 years, they’ve had on average three or four days a year with temperatures above 95 F. But that number is likely to grow to 40 to 60 days by 2050 given current trends.

Humans have the capacity to withstand all kinds of challenges but if we had 60 days that were really, really toasty, then that’s going to compromise people’s physiological and mental health, and their wellbeing.

What did you find about equity and tree cover in your research neighborhoods?

Our initial work was to look at a small, very well-established part of the city, about five square miles, not far from downtown. The area has very modest incomes, a mix of renters and homeowners, mostly Hispanic. The second biggest group were Asian Americans. Over half had lived in this particular part of the city for 10 years or more.

We did a census of all the trees, both on public and private property, and lo and behold there were 57,000 residents, but only 38,000 trees.

If we were to drive 10 miles west to Beverly Hills, that’s not the counts we would get. For every 50,000 people, there’s probably 250,000 to 750,000 trees. So that means that the local climates are different. It’s also the case that residents of Beverly Hills can likely go anywhere in the world they want to escape the heat. But in the neighborhoods that we examined, about 15 or 20% of the population don’t have a vehicle. So they’re going to rely on pedestrian movement or mass transit to get around.

In our study area there were also 19 public parks, and I think we had on average about four or six trees per acre, but the citywide average for all its public parks is something like 12 to 14 trees per acre. So first in this particular part of the city, we actually found there were less park acres per thousand people. And then with less acres, we still had less trees per unit area compared to the whole of the rest of the city.

What did you propose as potential solutions?

We produced some visualizations of scenarios that ultimately would lead to a more vibrant urban forest that could provide some much-needed benefits to the people who live in these neighborhoods.

We used five examples. Two were elementary schools, including one that currently has few trees and one that had a fair number of trees. But in both cases, we were able to illustrate how you could add trees and dramatically change the temperatures when children are in school and outside during recess.

And then we looked at a local park. Apparently the logic for parks and recreation in Los Angeles is that we need large open spaces to encourage people to participate in activities. But in Los Angeles for six or eight months a year now it’s so hot that nobody’s going to want to be out in the middle of an unshaded field.

What we did was we kept all of the facilities in the park and we showed how you can fill in some of these spaces such that people could still use them, but for large parts of a day there would be areas people could play and recreate that were partially shaded.

And then we did the same thing for a very narrow street where we would have to reimagine what part was used for traffic and what part was used to plant trees. And then we looked at the potential for doing that on a wide street.

Since COVID we’ve seen “slow streets” and streets where lanes have been taken away to support alfresco dining. Los Angeles is the capital of cars, and before COVID I never would have thought that possible. So, I think we’re seeing a moment of understanding that we can still support mobility, but the terms of engagement about what else we can do as well is changing. Certainly that’s my hope.

What are the next steps for your project?

I think an important part of our work has been to try and find other parts of the city that could benefit the most from these kinds of interventions and to focus our attention and energy on them. So in our next phase, we’re going to go south to the neighborhoods of Boyle Heights and City Terrace, and then to South Central.

One aspect that’s also continuing is looking at the ability of mature trees to help mitigate air pollution. What we want to try and understand is, what’s the effect of one tree [on air quality]? What’s the effect of two or three trees close to each other? What would be the effect of 50 trees?

Another thing we’d like to do in a larger project would be to establish urban forest laboratories. After we plant trees, we’d install soil moisture sensors with Wi-Fi so we could collect data in real time. That way we could understand more about the performance of the trees relative to the water we had available or we thought was available naturally.

And then the other part of our work is to better engage people to understand how they use their neighborhood, or how they would like to use their neighborhood, so we can plant trees in a way that connects with them and their everyday lives.

If we can do that, there are health advantages that would follow in terms of people being enabled to live more active lifestyles, breathe cleaner air, and have places close to where they live or work where they can take refuge from the heat.

We also hope to engage with the city and a group of nonprofits so that we can partner in both doing the science I’ve been talking about, and begin the task of planting trees in neighborhoods that lack green cover. We hope that the nonprofits can be the engine that plants those trees and that they can do it in a way where they grow a local workforce to maintain that forest.

![]()