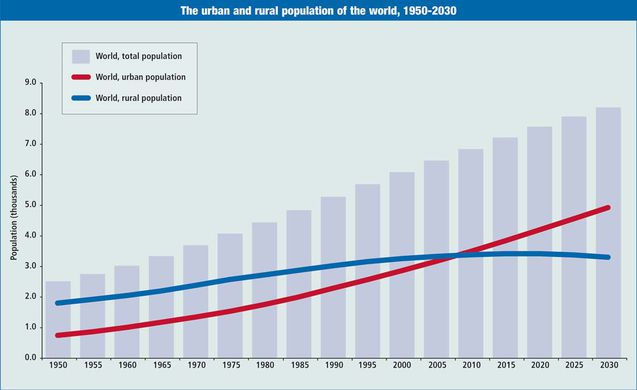

As much as we love and need nature, the human population is growing and moving to cities. In 1950 just 30 percent of the world’s population was urban, but that number is projected to rise to 68 percent by 2050. This phenomenon is giving rise to megacities — cities with populations of 10 million or more. In 1990 there were 10 megacities, but by 2030 there are expected to be 41. Ninety percent of this growth is occurring in Asia and Africa.

This rapid rate of urbanization, combined with the overall growth of the world’s population, will challenge our social systems, the way we manage natural resources, and the way we organize and build our cities. The question is, will the impact be negative or positive? The general perception is negative, but as someone who specializes in urban ecology I’m optimistic. Here’s why.

Perception of Cities

Urban areas have a bad rep when it comes to their relationship the environment. So much so that people generally consider cities to be the opposite of nature.

This isn’t without good reasoning. Since the Industrial Revolution, cities have been a place of concrete, glass, factories and office buildings. The first step in creating a new urban area was (and often still is) to remove all the natural environment’s features to make way for our rigid lines of zoning.

But our perception of urban life is changing. Over the past 50 years, environmental awareness has become more mainstream. From the first Earth Day in 1970 and creation of the Environmental Protection Agency to the rise of environmental advocates like Rachel Carson, David Suzuki, Sylvia Earle and David Attenborough, much has been done to educate and engage the greater public. In turn we’ve been able see cities in a new light.

Cities have adopted policies to incentivize LEED building certifications, urban forestry, brownfield site regulations, renewable energy, natural heritage, carbon offsetting, floodplain development restrictions, reduction of air pollutant output, stormwater management, open-space provisions in development, and most recently green roofs. These policies have led to greener, healthier cities that are more enjoyable to live in. With the implementation of these changes, we see fewer lawns and more tree plantings, fewer concrete channels and more naturalized watercourses, fewer water discharge and more constructed wetlands, fewer shingles and more green roofs, and more LEED-certified buildings.

It’s not just the public sector squeezing industries to go green — so is the private market. The demand from investors and residents to have access to parks, green buildings and a healthy living environment has created a lucrative market. According to the National Real Estate Investor, “Renters are willing to pay an extra $27.21 a month in rent to live in buildings that have green certifications — that works out to more than $300 a year per apartment in extra income.” Planting trees alone has demonstrated to raise property value from 5 to 18 percent in the United States. Roger Platt, the former president of the U.S. Green Building Council, has pointed out that “Investors now require green buildings as an international benchmark for their global portfolios.”

These government initiatives and the private market’s demand, coupled with technological advancements, are pushing a new potential for cities.

Potential of Cities

If government initiatives and private-market demand catch up and keep up with the rate of urbanization, we may just see our cities turn from concrete jungles to green paradises. Singapore is a shining example of how this could be accomplished. Between 1986 and 2007, the Singapore population grew by 68 percent, yet green cover grew from 35.7 to 46.5 percent. Certified green buildings account for more than a fifth of the floor area in the island city-state and aims to achieve a 35 percent reduction in the energy intensity of its economy by 2030 and have 80 percent green buildings.

By amplifying the blueprint of Singapore and other cities’ initiatives and bringing these models to the cities of developing nations, plant and animal communities may not only be able to survive but thrive alongside us. If this is achieved, it will be not as the result of limiting our abilities to develop but as a natural economic path to ensure cities stay livable.

Ecology and the Built Environment

Green roofs, urban forestry, green buildings, stormwater ponds, bioswales, living walls, parks, meadows and beaches will never replace the structure, quality and complexity of the ecosystems that existed before urbanization. But research has demonstrated the ability for cities to support significant levels of biodiversity (Aronson et al. 2014, Ives et al. 2015). As noted by Rosenzweig and Youngsteadt:

“Although cities are centers of consumption and land-use change, they represent a considerable opportunity for forwarding global sustainability and environmental goals. For example, cities are at the forefront in planning for climate-change adaptation and mitigation (Rosenzweig et al. 2010), and research into urban-ecosystems dynamics are revealing the potential for managing local and large-scale environmental change.” (Youngsteadt et al 2014).

Recognizing the limitations of urban ecology, there are several metrics that warrant optimism — for example, leaf-surface area. As buildings get taller and possibly more infused with vegetation, leaf-surface area may equal or exceed what’s estimated to have been present in the ecosystem that existed before disturbance on the site. To me this is an incredibly exciting prospect, as it could create a net gain of ecological services. The Bosco Verticale in Milan, Italy, is a good precedent for building that has succeeded in accommodating vegetation. This development has inspired a new generation of vegetation-infused buildings.

Species diversity is another possible optimistic metric. As we manipulate plant communities that we use, we have the ability to tweak those communities based on scientific recommendation to help support more diversity in biotic communities. A short communication by Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University on Promoting and preserving biodiversity in the urban forest notes:

“As our world becomes more and more urbanized, the urban forest will increasingly become an important reserve of biodiversity. We need to recognize the potential of urban areas to contain important amounts of biodiversity and work to promote that diversity.”

Species preservation is also a key potential product of urban ecology. We must remember that Ginkgo biloba went extinct in the wild but was able to survive due to human intervention. This could be expanded to species beyond trees with monitoring, habitat creation and protection. Other metrics may include greater volume of habitat, increased transpiration rates and increased biomass production, which could be achieved via vertical development.

The key benefit comes from vertical development’s ability to create more surface area, with the potential to generate more ecological productivity.

Future Cities

So will we allow cities to turn into concrete dystopias? Or will we create the green paradises that we deserve? By embracing urban ecology in the form of green infrastructure and biophilic design, we allow ourselves to work with nature, not against it.

We’re always learning about the benefits that natural features bring to the built environment, but we’re also learning more about plants and animals. Can we tailor the built environment to their needs? Can we couple our need of natural services with the needs of native ecosystems? Can we generate a net gain of ecological productivity?

Sustainability is the only way forward, and that’s why I’m excited about the future of cities for people, plants and animals. I’m grateful for all the unsung heroes who have created a foundation for green cities through science, education and implementation. I’m encouraged to be playing a part in facilitating it by working with governments, developers, architects and builders to implement green infrastructure and create green strategies. The future of urban ecology is not dark but bright.

© 2018 John Lieber. All rights reserved.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.