Maija Katak Lukin’s cousin plunged through the ice to his death while hunting for food for his family. Wenceslaus “Boyo” Billiot, Jr. and Stanley Tom continue to encounter new hurdles in their quest to relocate their communities threatened by encroaching seawater. And Henry Lickers worries about seasonal changes that are altering the dates on which his community holds traditional ceremonies.

These were some of the stories presented during Cultures Under Water: Climate Impacts on Tribal Cultural Heritage, a conference held in December 2017 at Arizona State University. Hosted by the university’s Indian Legal Program, the three-day conference brought together tribal leaders, cultural practitioners, attorneys and nonprofits that support tribal climate efforts. They discussed how they advocate for policy changes in a nation that’s dismissive, at best, of their unique cultures and history. And they all expressed a common goal: ensuring their communities survive in an era where ecosystems are changing almost daily.

In her remarks, Rebecca Tsosie, a Yaqui law professor at the University of Arizona and longtime native-rights activist, noted that the U.S. failure to recognize or respect tribal cultures is leading to tribes being left behind — or left out entirely — in planning and policy. Ninety percent of all coastal land lost in the United States is in Louisiana, she reported, yet the tribes whose homes are in the coastal bayous and wetlands that line the Gulf of Mexico, and who are on the front line of climate change, are “not even mentioned in state planning.”

Another Louisiana tribe, the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, is planning to relocate its entire community from a rapidly disintegrating island to further north in Terrebonne Parish. But they’ve run into some roadblocks, says “Boyo” Billiot, the tribe’s deputy chief — namely, the state of Louisiana, which wants to wrest control of the project away from the tribe, and the federal Fair Housing Act, which would force the 600-member tribe to accept non-native residents, since they lack federal recognition.

Stanley Tom feels the Isle de Jean Charles tribe’s pain. “We’re just one storm away from extinction,” says Tom, the tribal administrator for the Newtok Traditional Council, whose own relocation project in Alaska is snarled in red tape and a dispute with a neighboring community. “If we hadn’t built our own new village, we would have had to move to the city and become refugees,” Tom said. “We would have lost our lands and our culture.” He agreed with Billiot that the two communities should not have had to compete for the same relocation grants.

Lukin, who lost her cousin, said she isn’t just heartbroken at the loss of yet another community member to thinning ice: More broadly, she’s the superintendent of the Western Arctic National Parklands, headquartered in Kotzebue, Alaska. Her dual roles — as a wife and mother concerned with ensuring her family gets proper nutrition through traditional subsistence in a changing ecosystem, and as an executive charged with managing public lands — can sometimes be in conflict. Due to the thin ice, she has to send her staff out by air on projects; but, she said, “I’m worried that, by sending them out in airplanes, I’m contributing to climate change.”

Being a federal employee also meant that Lukin’s presentation wasn’t as detailed as it could have been; “I’m not sure how much I should say,” she replied when asked about how she felt about the changes occurring in her community. However, Lukin and Tom both stressed undeniable facts about the loss of sea ice and a rapidly altering climate. The changes affect subsistence food security, as well as sport hunting and fishing and other recreational activities by non-native hunters and other visitors in the 104-million-acre region under Lukin’s management.

“Climate change is one of those things that can uproot all people,” said Lickers, environmental science officer for the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne in Ontario, Canada, one of the Haudenosaunee peoples. “We’ve been concerned about climate change for a long, long time.”

Traditionally, Haudenosaunee seasons align with a moon phase, he said. “Each one of those seasons dictates when to plant beans or corn. We have ceremonies that are tied into those seasons that tell us what the world looks like.” But, those ceremonies have been disrupted, he reported. The ceremony associated with bean planting, for example, can no longer take place at the traditional time, because “the seasons have shifted,” he said.

It’s not just about seasons. Tsosie said that climate change is causing nothing less than “cultural genocide,” as governments fail to respect traditional ways of life and may even be sparking the “intentional destruction of cultural heritage.”

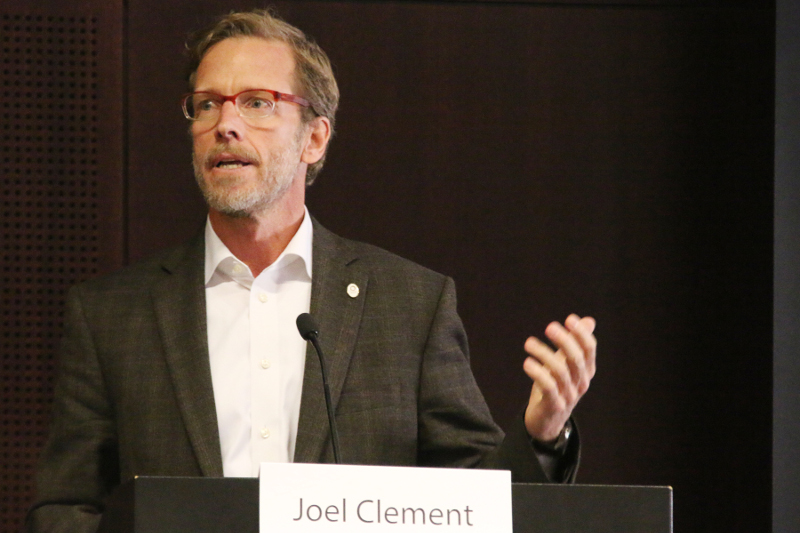

Keynote speaker Joel Clement echoed this, saying “There’s nothing climate change doesn’t touch.”

Clement, the former climate change lead at the Department of the Interior, said that the current administration is mounting an “all-out assault on anything that had to do with climate change — it’s like being led by a gang of vindictive fifth-graders.” Clement detailed how the Interior Department is working to eviscerate its staff, including slashing people of color and native people from the federal payroll by reassigning staffers with no notice and taking other moves to dislodge them from federal employment. “It’s clear that Secretary Zinke had no respect for the career ranks and the mission of DOI, and clearly wasn’t going to do any work on climate change,” he said.

So, in a political environment that has little interest in protecting tribal cultures, how do indigenous peoples assert their rights?

Robert Hershey, law professor emeritus at the University of Arizona, said, “Every attorney should read the Guideline for Considering Traditional Knowledge and Climate Change Initiatives,” which contains information on how to understand and abide by protocols when advocating for tribal communities.

Another possible solution involves a more radical approach. Tom Goldtooth, executive director of the Indigenous Environmental Network, averred that capitalism, and its addiction to fossil fuels, is the cause of climate change. Goldtooth’s solution was delineated in a report released at the conference that called for an end to public subsidies for fossil fuel extraction, including carbon taxes, markets and offset pricing.

Finally, Stephen Roe Lewis, governor of the Gila River Indian Community, offered another solution: Remain connected to tribal communities and their lands.

“Once those connections are broken, that’s when we become unfocused, a weaker society,” Lewis said. “My elders tell me, ‘Don’t forget our stories of resilience and adaptation.’ ” He added that tribes should create their own action plans, with a cultural foundation, to deal with climate change.

“We should all look to each other as our allies, as water protectors,” he said.

Whatever the future holds, one thing is certain: “We must be ready for changes,” Lickers said. “Societies that can’t change will collapse.”

© 2018 Debra Utacia Krol. All rights reserved.

No comments yet? How can this entire conversation on climate change & what the actual, real result is on human beings be treated as unimportant – well, not just that – but as if it doesn’t exist! What is being done to so many animal species and their habitat seems to be forcing them to extinction. I’m glad Mr. Clement is able to speak out and show exactly how little all of us – human and animal alike – matter to this “administration”. I wish everyone who contributed to this article much luck – because honestly I’m not sure any of us will be able to correct what is being done. I sometimes wonder if Trump & his cronies realize they live on the same planet that all of us do!