The modern wave of species losses that scientists have dubbed the sixth mass extinction threatens to unravel complex ecosystems, irrevocably alter our biodiversity, and endanger the survival of humanity.

From the largest elephants to the smallest fleas, tens of thousands of species are now hurtling toward extinction.

Among the most vital of these, believe it or not, are parasites.

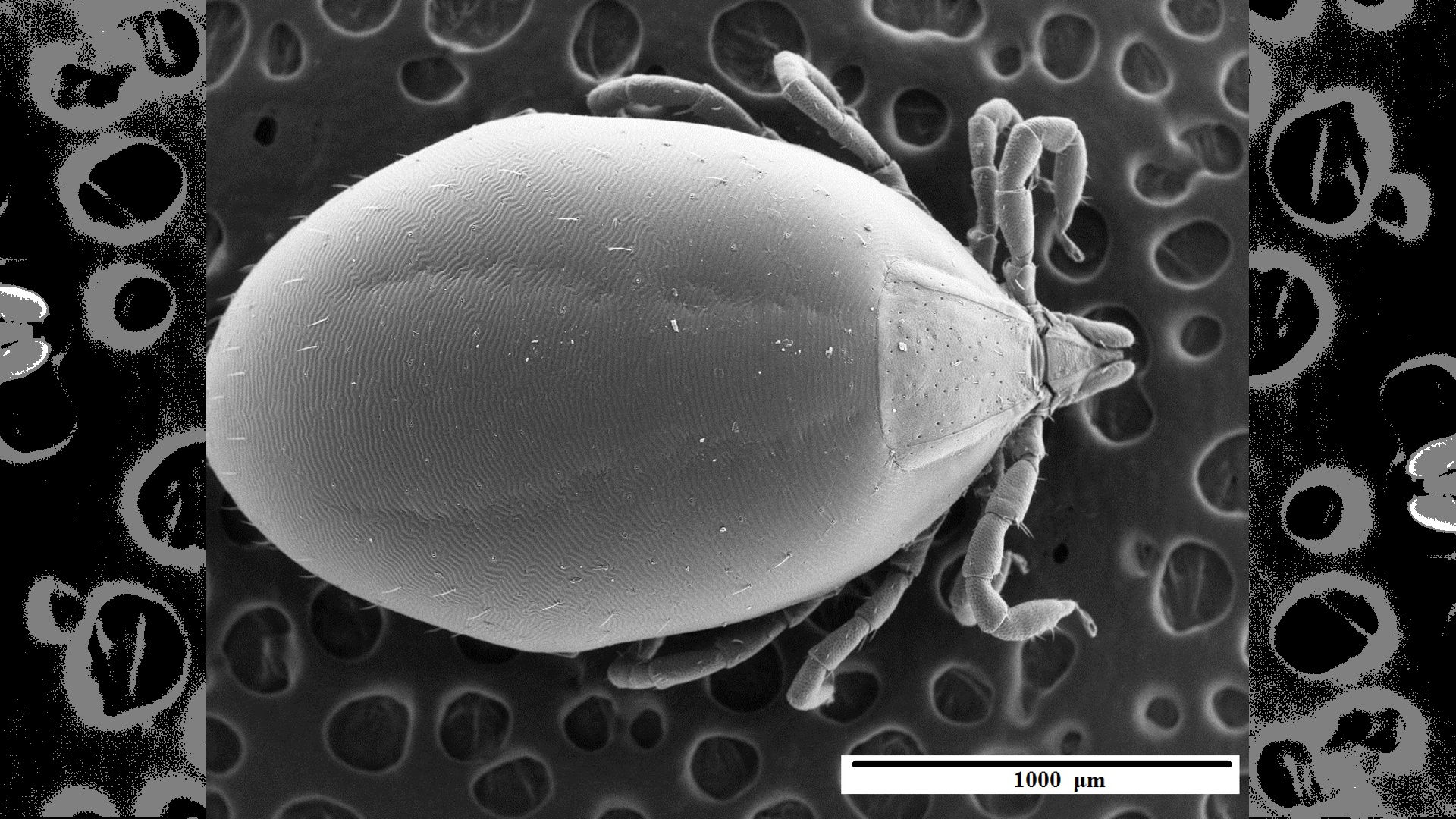

Although parasites are small and sometimes maligned, they’re incredibly important. A healthy parasite community is an indication of a healthy, balanced ecosystem, and many species play key roles in keeping their native habitats functioning properly. Some roundworms mediate competition between host species to help maintain higher levels of biodiversity. Certain tapeworms bioaccumulate toxic pollutants, such as heavy metals, and in doing so protect their hosts and wider ecosystems from harmful effects. New pharmaceuticals are even being developed from the saliva of ticks.

Clearly parasites have benefits to both humanity and nature, and their loss could have serious consequences.

But the first step in halting the global extinction crisis is determining which species are declining, and this can be tricky. The IUCN, which manages the Red List of Threatened Species, has established methodologies to determine a species’ conservation status, but this system works badly for parasites, largely because it wasn’t developed with invertebrates in mind.

One example is population size. Take a rare bird species that only has 500 individuals left, and a pinworm species that lives on those birds that consists of 10,000 individuals. Based on those numbers alone, the bird species would probably be viewed as more threatened. However, if those 10,000 pinworms only occurred in five of the 500 birds, then the pinworms would likely be much more vulnerable to extinction because the loss of that handful of birds could wipe them out.

Another challenge of conserving parasites is that, due to their small size and high species diversity, they often need to be killed to be identified and monitored. Obviously, killing a declining species to monitor it isn’t an ideal conservation strategy.

As a parasitologist focusing on rare, threatened and potentially extinct parasite species, I’ve often been struck by these problems, especially the need to kill a parasite population. And, like others, I wondered if there was a solution.

My colleagues Allen C.G. Heath and Pedro Cardoso and I have now provided a solution to the problem of viably assessing and conserving parasites, which we’ve presented in our new study in the journal Biological Conservation.

Our framework — which we call the Conservation Assessment Methodology for Animal Parasites (CAMAP) — starts by acknowledging the potential for host-specific parasites to become co-endangered, or even go extinct, when their hosts decline.

After that it outlines seven key criteria scientists can use to determine whether a parasite species should be considered threatened, endangered or critically endangered. These include geographic range, the number of infected hosts, the decline of host species, the rate of decline, and the conservation status of host species.

Our model also establishes goals conservationists can use to collect the most important information to determine a species’ conservation status and outlines what they can do if that data is not yet available.

Most importantly, this framework allows conservationists to less obtrusively survey parasite populations without wiping them out completely. Now, instead of having to try and collect, kill and identify as many parasites as possible to work out what’s going on with the population, we can instead sample a designated subset of the host population to address a parasite’s conservation needs.

And those needs are stronger than ever. In recent times we’ve lost a range of parasites, from fleas to flukes, to factors as varied as invasive species and our growing appetite for seafood. Some, such as the New England medicinal leech, have been lost for now and may yet be found and saved. And some, such as the Manx shearwater flea and Heath’s tick, are certainly still with us and urgently need conservation action.

Every extinction, including the loss of a parasite, is a species lost that we will never get back. With each extinction the carefully balanced tower of species that makes up our biome becomes more unstable and at risk of collapse. Yet until now conservationists have lacked the tools to assess Earth’s diverse parasite fauna and save it. Our model may finally provide the necessary mechanism to do so — and perhaps avert further extinctions before more of these vital, often ignored species vanish from the ecosystems that depend on them.

The authors have also made the paper detailing their framework available for download through ResearchGate.

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()

Previously in The Revelator:

Why We Should Care About Parasites — and Their Extinction