A popular reptile often found in pet stores is also one of the most heavily traded wildlife species on the planet — perhaps even more than pangolins. A decision pending later this month could help change that.

Tokay geckos (Gekko gecko) are colorful, foot-long reptiles native to Southern China through southern and Southeast Asia. Although widespread they’re increasingly threatened throughout their range, with millions of animals traded every year for use in traditional Chinese medicines, and to a lesser extent, as pets, which are mainly exported to the European Union and United States.

The species has been used in traditional medicine for hundreds of years and is sold throughout East and Southeast Asia in dried form or preserved in alcohol. Prior to export tokay geckos are typically slaughtered, gutted and stretched on bamboo frames and either dried in large kilns or sun-dried. After that they’re sold in male-female pairs to be boiled to create a tonic or wine, or ground into a powder and sold in pill form. It’s claimed that these products can treat skin problems, asthma, diabetes, cancer, erectile dysfunction, coughs and even HIV/AIDS. While there is some evidence for the medicinal value of tokay gecko derivatives (research has shown some anti-tumor properties), the majority of these claims are not clinically proven.

Indonesia: A Hub of Trade

The vast majority of the tokay geckos in trade are wild-caught, though large numbers are also labelled as purportedly bred in captivity.

Indonesia is the largest known exporter of tokay geckos, although the international trade from Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries is thought to number in the millions each year as well. Unfortunately little information on exports from other range countries is available. Although Indonesia did not, until this year, allow the export of dried specimens, research found that high levels of trade are still taking place, with an estimated 1.2 million dried geckos exported to China in 2006 alone. In 2011 authorities in Hong Kong seized 7.45 tons of dried tokay geckos en route to China from Indonesia.

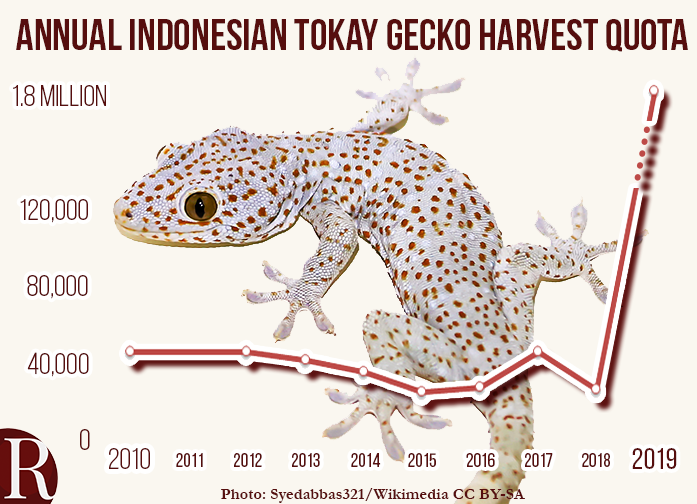

Tokay geckos are not on Indonesia’s list of protected species, and trade in wild-caught specimens is subject to an annual harvest and export quota system. These quotas are known to be abused and ignored by traders, and are most often not based on science in the first place.

These quotas over the years have remained relatively stable, varying from 23,850-45,000 geckos annually from 2010 to 2018. However, this year the Indonesian Government inexplicitly raised the quota to a staggering 1.8 million animals, of which 21,250 are allotted for the pet trade and, for the first time, 1,778,750 are for the consumption trade.

Captive vs. Wild

Captive vs. Wild

So where do all of these millions of geckos come from?

Some dealers claim Indonesian geckos are captive-bred. Indeed, commercial captive breeding of wildlife is sometimes viewed as a means to remove or reduce the pressures of overexploitation on wild populations. But that’s probably not what’s happening here. Research has shown that such schemes are also frequently used as a mechanism to launder wild-caught specimens.

For example, in 2014 the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry allowed six companies to export a total of more than 3 million live, supposedly captive-bred tokay geckos for the pet trade. Regardless of the fact that there is hardly an international demand for this many tokay geckos in the pet industry, the logistics involved in breeding millions of geckos for the export market make such a claim questionable, to say the least.

In order to produce just a million adult-sized geckos, a facility would require 140,000 breeding females, 14,000 breeding males, 30,000 incubation containers in continuous use year-round and some 112,000 rearing cages — with a 100 percent hatchling survival rate. Fundamental care of these geckos would require hundreds of employees and a constant supply of food, all of which add significantly to the overall costs.

In reality, the exporting companies involved were found never to have bred this species in commercial numbers and were known to supply the trade with wild-caught reptiles for the medicinal and meat trade, not for pets — regardless of the fact that the quotas stipulated export was of live specimens for the pet trade only.

Indonesia is not alone. Protection for tokay geckos in the range states varies by country and international trade is currently uncontrolled — there are currently no mechanisms in place to assist countries in monitoring or regulating international trade or to collect accurate statistics on the international trade volumes. As such, the international trade is largely a free-for-all.

And all of this activity comes with a cost for the species. Studies have shown that such high trade levels are threatening wild populations, in particular in Indonesia and Thailand. Population declines have also been reported in Bangladesh, mainland China, Myanmar, the Philippines and Viet Nam. In Bangladesh, populations have reportedly declined by as much as 50 percent.

What Comes Next?

In view of the large-scale illegal and unsustainable trade — and taking into consideration the enormous numbers of wild-caught specimens laundered through bogus captive-breeding operations — India, the Philippines and the European Union have submitted a proposal to include the tokay gecko in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The proposal, which would place strict controls on trade, is due to be voted upon during the 18th Conference of Parties, held this month in Switzerland.

Considerable evidence has been that levels of trade in tokay geckos are extremely high and largely illegal and/or unsustainable and that wild populations are reportedly in decline from a number of range countries.

Obviously those benefiting from the current illegal and unsustainable trade will oppose this proposal. However it needs to be clear that listing this species in CITES Appendix II would not prevent trade. Instead it would provide a mechanism through which range countries could, with the cooperation of all CITES Parties, control, regulate and monitor the trade through a permit system, providing an opportunity to obstruct illegal trade.

Such oversight and control of the trade would be of great benefit to range countries wishing to protect or sustainably trade their tokay gecko populations and assist in achieving population recovery in those range countries where this species has begun to decline.

The opinions expressed above are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()

3 thoughts on “Millions of Tokay Geckos Are Taken From the Wild Each Year. International Protection Could Help Save Them”

Comments are closed.