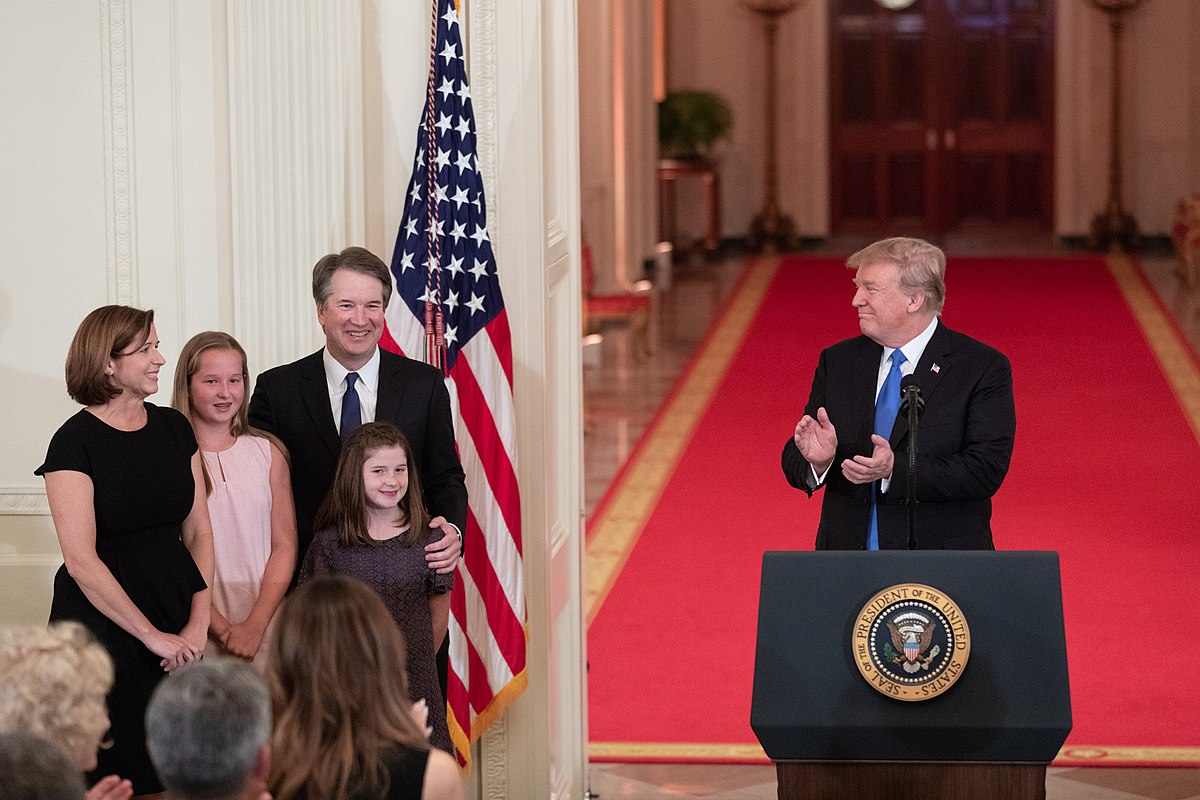

Legislators and law scholars last week began officially picking through the legal life of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to determine whether he’ll fill the Supreme Court seat left by retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy. Despite vocal opposition from Democrats, Kavanaugh has strong Republican support in a Senate controlled by Republicans.

“It’s his to screw up, I guess, and I don’t see him doing that,” says Patrick A. Parenteau, a professor of law and senior counsel in the Environmental and Natural Resources Law Clinic at Vermont Law School.

Parenteau is among those in the environmental-law field who believe that the potential addition of Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court could have a major impact on crucial environmental decisions. Environmental groups will need to change their legal strategies, believes Parenteau, to find success with the court’s new likely composition.

And others also believe that a shift may be coming in the Supreme Court in a key area that could make a lasting mark on environmental regulation.

A Monumental Shift

Kavanaugh’s past decisions have been heavily scrutinized by experts around the country to better understand how potential future Supreme Court cases could be shaped. One analysis, by the consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen, found that he voted or wrote decisions against “public interest” 87 percent of the time in decisions involving the environment, consumer protections and worker rights.

More broadly Kavanaugh’s leanings, in concert with some of the other justices’, could also shift the court away from long-held thinking on the role of the government’s administrative agencies, which could significantly alter the interpretation of laws on the environment and public health.

“What affects environmental law, public lands and natural resources law the most is the way the judges understand the power of administrative agencies in our government,” says Sean B. Hecht, who’s co-executive director of the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and a professor at UCLA School of Law.

Typically, laws having to do with the environment, public lands and natural resources at the federal level are written by Congress but implemented by administrative agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency. In some cases what Congress directs the agencies to do is very specific, such as regulating a list of chemicals in a particular way, says Hecht. “But much more often, Congress writes the laws more broadly and flexibly than that and it is the job of an agency like EPA to give life to what Congress has suggested,” he says.

So, for example, when it comes to something like the Clean Air Act, it’s Congress’s job to provide broad authority and the EPA’s job to use scientific evidence to determine what pollutants endanger public health and welfare, what kind of harms they cause and at what level of concentration, and then to act on that information.

When an agency’s actions are challenged in court, whether by industry or environmental groups, it’s the job of the court to decide whether the agency acted in keeping with the confines of the law. And these are important decisions, Hecht says. “They cut to the core of our regulatory system and our public-lands management system. The way that judges approach these issues is crucial to the ability of administrative agencies to work effectively.”

However, when it comes to the way Kavanaugh has ruled on these types of principles, Hecht says, the judge appears to take an approach that would narrowly restrict the role of administrative agencies. In a 2012 case that came before the D.C. Circuit, he wrote in the majority opinion that the EPA had overstepped its authority in regulating air pollution that crossed state lines — a decision that was later overturned by the Supreme Court.

In another example last summer, Kavanaugh and the D.C. Circuit ruled that in 2015 Obama’s EPA overstepped its bounds under the Clean Air Act in trying to regulate some hydrofluorocarbons.

“However much we might sympathize or agree with EPA’s policy objectives, EPA may act only within the boundaries of its statutory authority,” Kavanaugh wrote in the decision. “Here, EPA exceeded that authority.”

Hecht says that’s a big worry for those who think the federal government should be empowered to take those types of actions. “I think the concern that a lot of people have is that there are justices like [Neil] Gorsuch, and potentially a new Justice Kavanaugh, who might start from that much more narrow view of what agencies are empowered to do, which would hamper efforts to protect the environment,” says Hecht.

And that would be a big change. “We expect Congress to shift as the political winds shift, but I don’t think we should expect for our courts to adopt a dramatically different view of the balance of power,” Hecht says.

There is a long legal precedent of Congress empowering agencies to regulate. “There is this vision that has been applied for the last 40 or 50 years, which is that it is constitutionally sound to empower agencies to use their judgement based on the laws that Congress has written,” says Hecht. For decades this was an idea shared by both conservative and liberals. Justice Scalia, known for his conservative views, wrote the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in the 2001 case Whitman v. American Trucking that reaffirmed the EPA’s authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate pollutants that endanger public health and welfare.

The much newer conservative viewpoint, which seems to be shared by Kavanaugh, is that Congress must explicitly tell an agency what to do, and even then, the directive should be to only do that one thing.

“You can probably see that would be a pretty dramatic change in the way that agencies operate,” says Hecht. “At its extreme it could invalidate some of the laws that we rely on to protect the environment, like parts of the Clean Air Act.” Congress has given the EPA broad instruction in the Act to figure out which pollutants are bad for people’s health and how to best regulate them. But under this narrower version of agencies’ power, Congress would need to be much more precise in dictating the EPA’s specific actions for each type of pollutant.

Parenteau points to Massachusetts v. EPA, the 2007 case in which Justice Kennedy cast the deciding vote, giving the agency authority to regulate carbon dioxide emissions under the Clean Air Act. The ruling has been crucial in helping to shape laws addressing climate change.

“Kavanaugh has all but said out loud he thinks it was wrongly decided,” says Parenteau. “If he gets a chance to examine whether the Clean Air Act of 1970 authorized the EPA to adopt this broad sweep of regulation of a substance that was not even yet considered a pollutant in 1970 — how could it be? —he would say that looking at the way the statute is worded and the original intent the EPA has no authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon.”

What the Future Holds

The first case on the Supreme Court’s docket when it reconvenes Oct. 1 is Weyerhaeuser Company v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, which involves a clash over endangered species and private property.

Parenteau says the case, which involves the fate of the endangered dusky gopher frog (Rana sevosa), will show early signs of the impact of both Kavanaugh and Gorsuch on the court. (The dusky frog was protected following a lawsuit by the Center for Biological Diversity, publisher of The Revelator.)

Other important environmental decisions are looming on the horizon, including the question of how far the Clean Water Act goes in protecting streams and wetlands and a legal ruling on whatever’s left of the Clean Power Plan. One of the big future issues will be whether EPA has the authority under the Clean Air Act and other laws to address climate change.

Parenteau says we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface, as a society, when it comes to regulating carbon pollution. But he admits he’s optimistic that Kavanaugh’s opinions might evolve over time if he’s confirmed. “You’ve just got to hope that he can be persuaded that the courts really do have a legitimate role in democracy to assert themselves when they see abject failure of government to address these problems,” he says.

The future, though, is by no means a rosy picture for those seeking stronger environmental protections — and that, Parenteau believes, should also change the game plan for environmental groups.

“We’re going to have to be really careful with the language we use, the cases we pick, the face of the case, and who’s bringing the case,” he says. “We are going to have to stay out of the Supreme Court as much as we possibly can.”

Although he explains that environmentalists shouldn’t give up fighting bad projects and bad agency decisions, he feels they need to devote more resources to electoral politics, starting at the grassroots.

But when it does come to legal challenges, those litigating on behalf of the environment need a different set of tactics.

“I’ve read his opinions. They’re masterpieces of facile legal thinking,” says Parenteau. “You can’t beat him with stock kinds of arguments and appeals to what’s right and what’s the best policy. You’re going to have to get down into the weeds of the language of statutes and the language of the Constitution. You are going to have to do a lot of homework parsing the way he thinks to figure out how can you get to him.”

Whether or not Kavanaugh gets confirmed, he likely fits the model of any other potential Supreme Court nominees under the present administration, which has routinely sought to roll back environmental protections. It’s all but guaranteed that with Justice Kennedy’s swing vote gone, the court will reliability tip conservative — and that all but ensures an upheaval in the nation’s environmental laws and protections.