Wildlife is traded for many reasons, but the trade in painted woolly bats is among the most senseless. These animals’ unique and beautiful coloration is the reason behind their popularity and the growing trend of using the species for decorative purposes — a trend we hope to help end.

Species name:

Painted woolly bat (Kerivoula picta)

Description:

This tiny bat (weighing just over an eighth of an ounce, or roughly 5 grams) has a spectacular appearance, with bright orange fur and mostly black wings, within which the finger bones are surrounded by bright orange skin. Their tiny eyes are barely visible because of the thick, long fur covering most of the face. But you can’t miss their big ears (which remind us of Mr. Spock), needed to hunt small arthropods, especially spiders and insects, by echolocation.

Where it’s found:

Painted woolly bats live in southeastern China, South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka), and Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam). Their habitats include dry scrub and agricultural fields (especially banana plantations — they often roost alone or in small groups under dried banana leaves, within 6 feet of the ground).

IUCN Red List status:

In 2020 the IUCN changed the conservation status of the painted woolly bat from Least Concern to Near-Threatened based on a suspected 25% population decline.

Major threats:

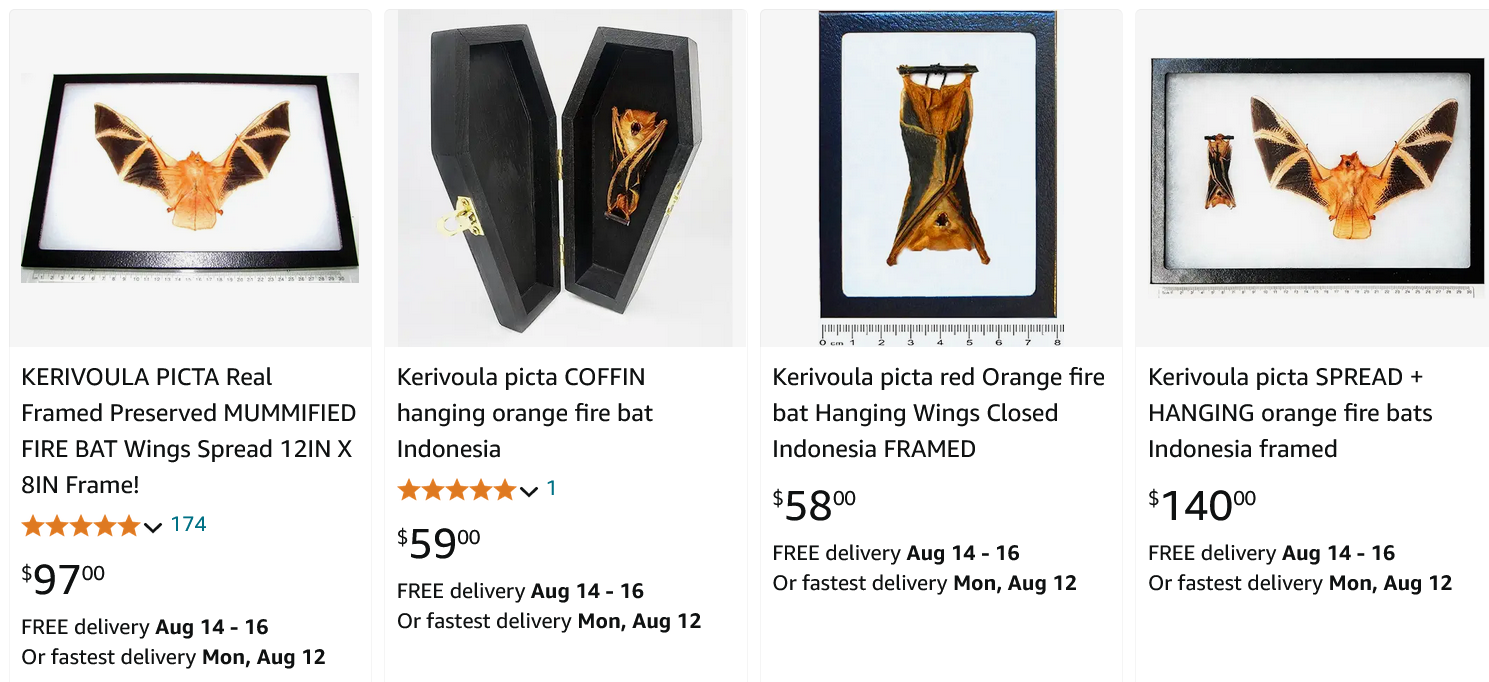

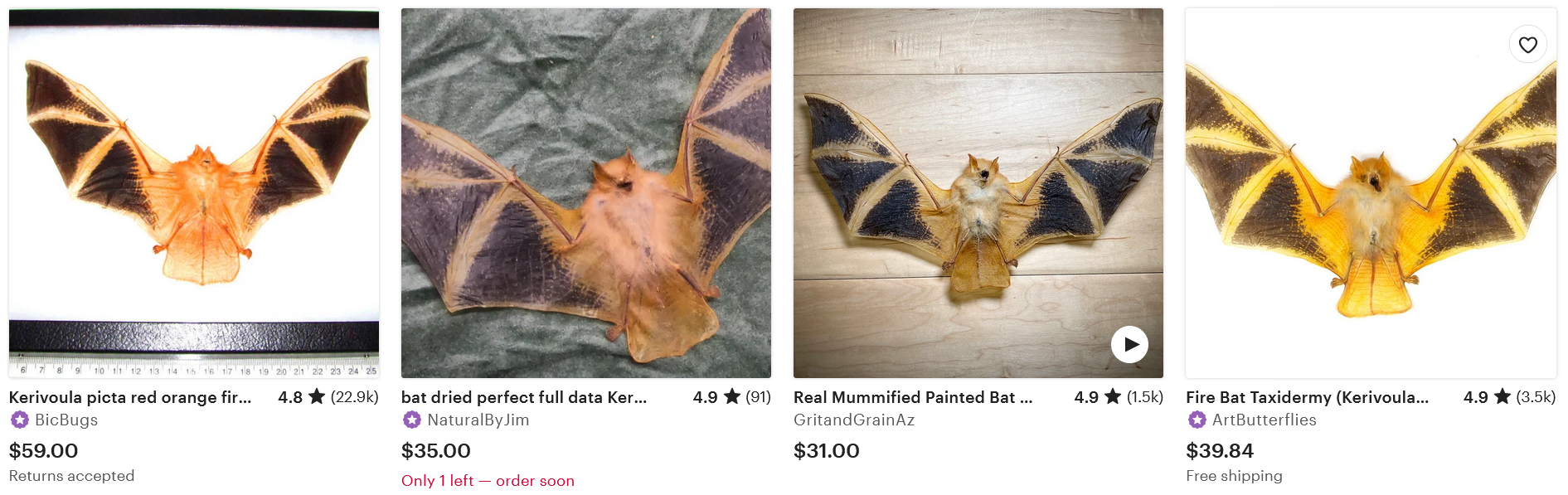

The biggest conservation threat to the painted woolly bat is likely attributable to their distinct looks, which appeal to collectors of taxidermied-bat and other oddities for decorative purposes. These can be purchased at numerous online and physical marketplaces. To satisfy that demand, bats are hunted in the wild — there’s no captive breeding of this species. Other threats include disturbance of their roosts, notably in plantations, and habitat destruction (especially logging and the conversion of agricultural areas to residential or other land uses).

Notable conservation programs or legal protections:

While the painted woolly bat is protected at national levels in some Asian range countries, international trade is not regulated and there’s very little in the way of protection in consumer countries. Clearly, what protection is in place is not sufficient to prevent online trade in North America and the European Union. The goal of our work is twofold: to have strong legislation in consumer countries to prevent import and trade and to have international trade regulated through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Ultimately we’d like to see the major online trade platforms that enable and facilitate the trade in painted woolly bats take action and effectively disallow any further online advertisement and trade.

Our favorite experience:

While studying the trade in painted woolly bats, we reviewed hundreds of Amazon, eBay, and Etsy listings for taxidermied bats offered to consumers in the United States over a three-month period. We needed to record how many of the specimens were painted woolly bats. Scouring thousands of photos of dead bats was no fun at all. But we were motivated to get through the task by our conviction that this work could, by documenting the extent of the trade, lead to effective legal protection. Indeed, it has resulted in a petition now before the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to add Kerivoula picta to the Endangered Species Act — a move that would make buying and selling of the species in the United States illegal. (Full disclosure: The Center for Biological Diversity, publisher of The Revelator, filed this petition in conjunction with Chris’s organization, Monitor Conservation Research Society.)

More recently we began looking at the trade in Vietnam, which we expect to generate the evidence we need to encourage the government to take action. Further evidence of illegal and unsustainable trade will, ideally, catalyze action from range and consumer countries to list this species in one of the appendices of CITES.

We hope this work pays off and that painted woolly bats will one day enjoy legal protection. But more challenging, and perhaps more urgent, is reducing demand. We need buyers and would-be buyers to stop purchasing bats in picture frames, bats made into hair clips, Halloween decorations made from bats, and bats used to hang on Christmas trees. Wake up, folks — buying these items not only contributes to the decline of this species in the wild but also supports illegal wildlife trade networks.

What else do we need to understand or do to protect this species?

We found hundreds of individual painted woolly bats offered for sale just in the small sample of listings we examined, covering three shopping websites in one country. But we know they’re sold year-round on dozens of other websites and in physical shops in many other parts of the world.

Like most bats, painted woolly bats reproduce slowly (they only have one pup per year) and live much longer lives than expected considering how small they are. In other words, they have a slow life history. Unfortunately, all species with slow life histories are intrinsically vulnerable to overharvesting because of how long it takes their populations to rebound from declines. And as painted woolly bats are usually solitary and maintain non-overlapping home ranges of 12-14 acres, they are relatively scarce on the landscape compared to other bat species. This suggests that hunters likely search large areas and kill all the individuals they find to satisfy the demand.

To accurately estimate how much of a threat this trade poses, we must evaluate the offtake (number and demographics of harvested painted woolly bats) against the potential availability of individuals. These are total unknowns, as this bat’s ecology has barely been studied. So we need on-the-ground studies to gather data on population sizes and trends. To gauge total offtake, we can conduct a thorough investigation of all shipments of bats that are seized at U.S. ports of entry and identify all specimens to species (using genomics, if necessary, as skulls and skeletons are impossible to identify visually). This would allow us to get a sense of offtake for many other bat species, too.

We also see the need for social-ecological network analysis. This approach would allow us to identify and visualize all the stakeholders (human and nonhuman) in this trade and the connections between them. That would reveal the ecological roles and importance of painted woolly bats in ecosystems and to human wellbeing, while also showing the key human actors and links that could be used as levers to end this trade.

What can you do to help? Obviously, do not buy painted woolly bats. But also, educate others around you and inform them of this problem — spread the word. Write to your governments and ask if painted woolly bats are protected in your country, and if not, why not? Finally, support efforts to prevent the poaching and illegal trade in painted woolly bats. These bats may weigh next to nothing, but public support for them is everything.

Update: Etsy officially banned bat sales on its platform on July 29, but relies on visitors to report listings that remain for sale.

Key research:

-

- Coleman, J.L., Randhawa, N., Huang, J.C.C., Kingston, T., Lee B.Y.-H., O’Keefe, J., Rutrough, A.M., Tsang, S.M., Thong, V.D., Shepherd, C.R. (2024) Dying for décor: Quantifying the online, ornamental trade in a distinctive bat species, Kerivoula picta. European Journal of Wildlife Research. 70, 75.

- Huang JC-C, Lim LS, Chakravarty R (2020) Kerivoula picta The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T10985A22022952. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T10985A22022952.en

- Lee BPYH, Struebig MJ, Rossiter SJ, Kingston T (2015) Increasing concern over trade in bat souvenirs from South-East Asia. Oryx 49:204–204.