Animals have individual personalities, can adapt to changing conditions, and can make decisions based on social learning in ways that shape shared human-wildlife spaces. That means they can play an active influence in their own conservation, argues a new paper published in Conservation Biology.

According to the authors, wildlife conservation and management could improve the outcomes of interventions such as translocations, reintroductions and resolving human-wildlife conflicts by explicitly acknowledging these traits — described as “animal agency.”

“Animal agency is an emerging way of seeing animals as ‘helpers’ in their own conservation efforts,” says Matthew Hayek, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University and the paper’s senior author. “Rather than working against their own idiosyncratic behaviors, conservationists are paying attention to individual animals’ quirks, seeing differences between small groups, and increasingly working with them and achieving better outcomes.”

An Open Mind

But according to the paper, wildlife conservation management usually overlooks the concept of animal agency and prioritizes, as the authors put it, “metrics that treat animals primarily as quantifiable stock.”

To understand this gap, the authors reviewed 190 published evaluations of policies and programs and identified three underlying assumptions that may undermine their results.

First, the policies presuppose that animals from the same species all “behave uniformly” and that behavior mostly remains the same in different contexts.

Second, they assume that animals will revert to an “idealized state of wildness” when they are placed in appropriate wild habitats.

Third, the policies conceive of relationships between humans and wildlife in a narrowly biological or economical way and downplay cultural relationships between humans and animals.

But animals are not mathematical formulae that provide the same answer every time. If they deviate from wildlife managers’ assumptions, they can inadvertently undermine human-established conservation goals.

The paper lays out several documented cases where animals acted in unanticipated ways, demonstrating their agency and thwarting management efforts in the process.

For example, elephants in Kenya had been detusked to prevent them smashing fences, but they devised new ways of breaking through barriers. Leopards in India were translocated to a protected nature reserve but soon returned to the edges of an urban area, where they conflicted with humans. And in the United States, kangaroo rats that had been translocated to newly restored habitat ended up losing previously established social connections, which resulted in low reproduction and survival rates.

Survival rates can also suffer when “misbehaving” animals earn themselves the label of “problematic” — which can result in their relocation or even their extermination.

But those are reversible problems. The paper also highlights how integrating animal agency in wildlife management and conservation can shift priorities and help policymakers and practitioners shape and implement conservation plans.

To take one aspect of animal agency — personality — bold individuals are more likely to tolerate human disturbance, use conservation infrastructure, or colonize new areas. This has implications for interventions like wildlife-corridor planning, the authors argue, because the scientific models for how animals use corridors present “strikingly different results when different behavioral characteristics are included.”

As another example, accounting for social learning among groups can shift conservationists’ focus from preserving the reproductive potential of younger group members to preserving a group’s culture and generational knowledge. As the case of the kangaroo rat shows, maintaining social ties for some species can matter more for the survival of individual animals than placing them in an ecologically correct habitat.

Collective Agency

This kind of approach can save not just individual animals but whole animal communities.

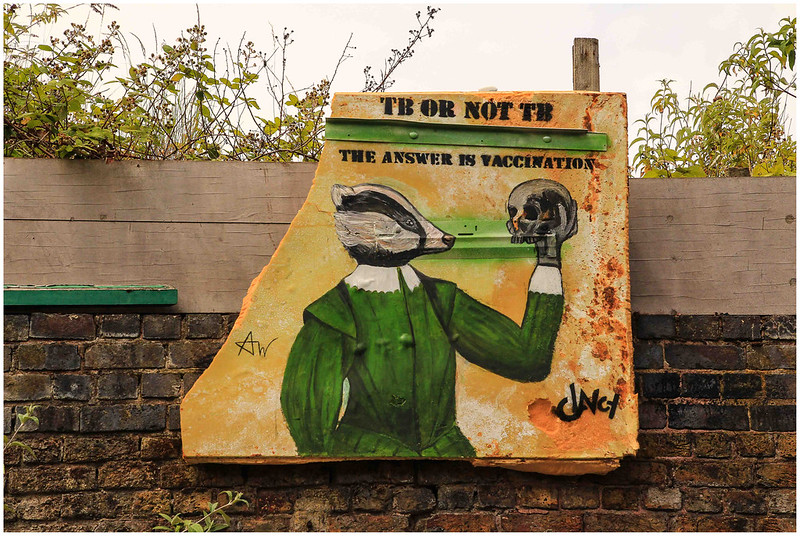

In the United Kingdom, the success of vaccinating badgers against bovine tuberculosis as an alternative to culling requires engaging with their agency — something I’ve experienced as a badger vaccination volunteer for the past two years. The badgers must be habituated to taking bait — peanuts — and going in and out of traps over a period of about two weeks. For each badger community, volunteers use their own knowledge and that of landowners — such as how bold or shy the animals are, how they behaved during previous vaccination rounds, and how they use the land around their dens — to determine where to set bait and assess the likelihood they will be trapped successfully.

A more famous example occurred in the Dutch city of Leiden in 2014, where conservationists saved gulls from a proposed cull by helping the city implement measures to change the behavior of both humans and birds.

The gulls, lured to cities by the destruction of their natural coastal habitats and the promise of easy meals, began nesting noisily on rooftops, tearing open garbage bags, and stealing food. Some species, like the black-headed gull and common gull, are in decline, but one Dutch politician proposed lifting their legal protections and shooting them.

That met with opposition from De Vogelbescherming, a bird-protection organization, which offered several alternative interventions. These included using ropes to make rooftops unsuitable for breeding, using stronger garbage bags that could not be torn open, educating people against feeding the birds, creating nesting islands by the coast, and observing which places the birds preferred.

This approach, philosopher Eva Meijer wrote in the 2016 book Animal Ethics in the Age of Humans, “illustrate[s] how we can experiment with interspecies decision-making … When conflicts arise, there needs to be communication [between species] about who can live where.” Without the agency-based methods of conservationists, culling as a management strategy might have prevailed and undermined efforts to preserve dwindling gull populations.

Solving Problems

While many management policies contain shortcomings when it comes to thinking of animals as agents, “on the ground, there are people seeing these phenomena regularly,” says Hayek. This means that knowledge of animal agency may inform decisions made by wildlife managers even when it’s not officially part of policy.

One example cited in the paper comes from a 2016 study on human-bear cohabitation in the Colorado Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. In 1985 Colorado Parks and Wildlife introduced a management policy known as the “two-strike directive” to manage so-called “nuisance bears.” One strike for nuisance behavior, such as breaking into a house to find food, gets a bear trapped, tagged and relocated; a second strike gets them killed. The study explained that the directive — which is still in place — is based on assumptions about bears adapting their behavior in a predictable way to the cues given to them by humans about where they are and are not welcome, such as relocating them to “‘prime’ bear habitat.”

But when bears interpret the cues differently, or behave in some unexpected manner, the wildlife managers who implement the directive learn and adapt their methods accordingly.

“The wildlife managers I spoke to over there acknowledge that these bears have agency, they are individuals, they have a certain way of behaving,” says Susan Boonman-Berson, a co-author on the study and a researcher in human-wildlife conflict, who spent two months in Colorado in 2012 observing the interactions between black bears and wildlife managers. “They want to understand these specific animals, and they don’t see them just generally as bears.”

One manager Boonman-Berson interviewed described how different bears have their own “methods” of getting into people’s property. The manager had to observe and understand the signs they left behind at the site of a break-in to determine the best management strategies. For example, a bear who broke into a car because it still smelled like the owners’ recently purchased cantaloupes could be lured to a trap with fresh fruit.

This also helps managers avoid trapping the wrong bear, perhaps one who might simply wander into a trap set for the “problem” bear. Ironically, this can earn the wrong bear a strike because, by entering the trap, they’re considered to have become more habituated to accessing “easy food.” Recognizing animal agency can also challenge the idea of “problem” or “nuisance” animals that policies like the two-strike directive seek to address. Humans can inadvertently attract animals by providing easy access to food, making urban spaces more attractive than the prime habitat.

“When we attract them and feed them and are really actually inviting them to come closer,” says Boonman-Berson, “I think we should not speak about the ‘problem animal’ because the animal is not a problem.”

The answer, she says, often involves focusing on educating humans rather than managing animals.

“They also call it people management [in Colorado],” says Boonman-Berson. “It’s not black bear management, it’s people management.” The wildlife managers she observed educated residents by encouraging them to secure their trash, keep doors locked, and not grow fruit trees inside areas where they didn’t want bears to venture. This is an example of how humans and animals both contribute to shaping shared environments — one of the tenets of animal agency.

Barriers Remain

These examples show some of the possibilities for integrating the concept of animal agency into wildlife management — but also the challenges. Different aspects of animal agency — personality, social learning, adaptability, and relationship with humans — may be more or less relevant depending on the species and contexts, Hayek and his coauthors argue in their paper. They also acknowledge that there are barriers to a more widespread integration of animal agency into conservation practices, since it introduces “nonuniformity, uncertainty and complexity at the modeling, planning and implementation stages” and might require “more complex, expensive and computationally intensive simulations.”

Indeed, the integration of animal agency into conservation plans has so far been “piecemeal, temporary, and not very popular,” Hayek says.

But, he adds, acknowledging the diversity of behaviors and experiences among animals of the same species can at least start to challenge the assumptions that guide much wildlife management and conservation.

“We can find plenty of examples of animals and humans actually learning from one another in a pretty rich way,” says Hayek. “And that is kind of a mark against the top-down nature of some conservation programs that don’t look to animals for direction.”

Previously in The Revelator:

The Surprising Clue to Reducing Human-Elephant Conflict: Minerals

![]()