Shongaziph Ngcongo awoke one windy night in August to find her thatched-roof house ablaze. She just managed to grab her six children and a few meagre possessions before escaping the wildfires that burnt down her valley.

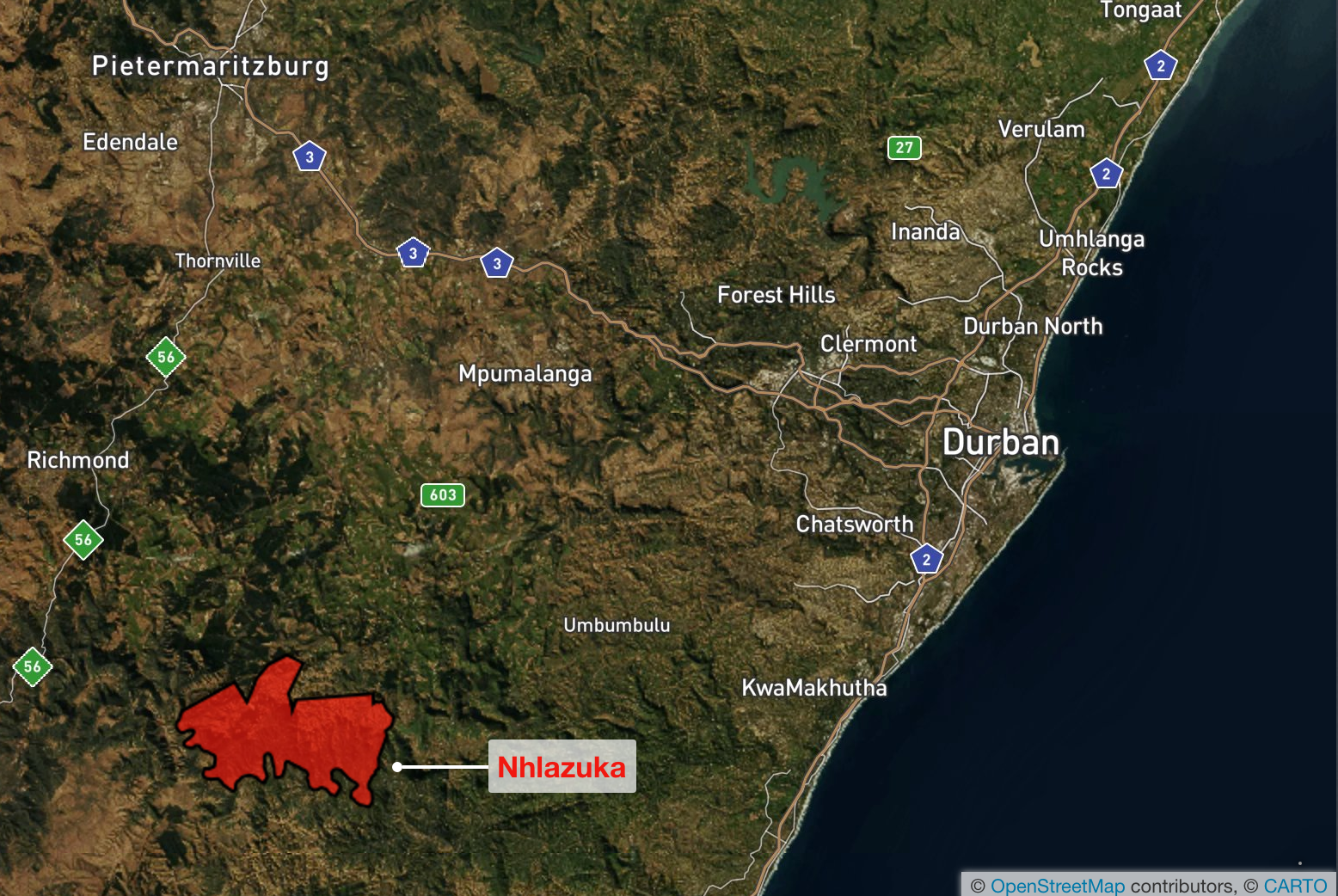

Ngcongo lives in an idyllic-looking rural community located in hills above the Nhlazuka valley. In this rural part of KwaZulu-Natal, people live in traditional rondavel homes that are spread out among thornveld valleys. Steep hillsides make the homesteads easy targets for wildfires, especially those with thatched roofs.

“When fires start in the valley, sparks fly up on top of the thatch and then the houses start burning,” says community member Bono Cwazibe.

“When fires start in the valley, sparks fly up on top of the thatch and then the houses start burning,” says community member Bono Cwazibe.

Many of the wildfires are caused by people hunting bush pigs: they set the bush alight to flush out wild animals, and when the flames get out of control they spread rapidly through the dry thornveld scrub and grasslands. The community has no firebreaks, so their livestock, crops and homes are vulnerable to fire attacks.

The peak fire season in Nhlazuka, which has a population of 7,903, is in August as wind speeds reach up to 100 knots an hour. Wildfires cause loss of grazing for livestock, and some community farmers have had their sugarcane plots destroyed.

Every year an average of three to four wildfires ignited in Nhlazuka spread to commercial farming land and timber forests in neighboring areas. These wildfires are often detected only after they have entered the commercial properties, and by then the damage is done.

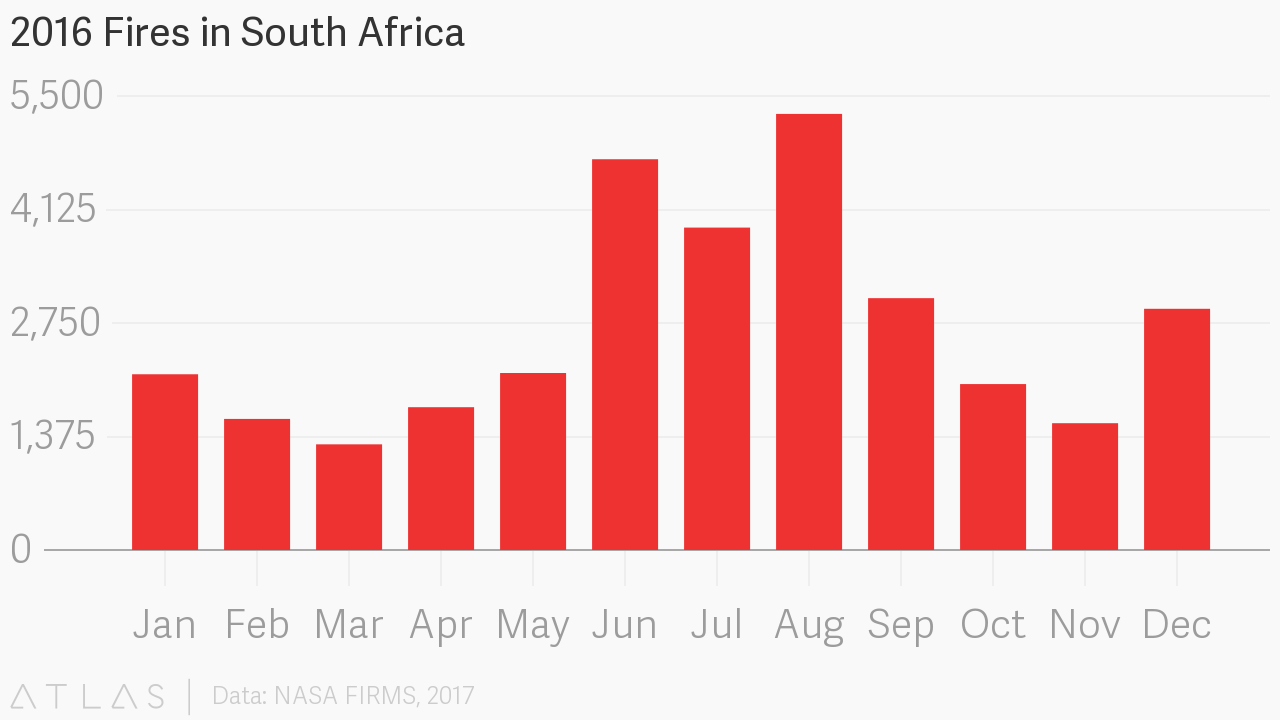

Nhlazuka’s fire factory is not isolated: at least 16,027 fires were detected across South Africa between January and June this year, statistics from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Fire Information for Resource Management System show.

The cost of fire incidents amounted to more than R1-billion ($750 million) in damages across the country in 2015, according to The Fire Protection Association of Southern Africa.

Building Resilience

With temperatures rising and drought spreading due to the impacts of global climate change, neighbourhoods such as Nhlazuka that are vulnerable to wildfires need to build up resilience.

Nhlazuka is part of the uMgungundlovu district municipality, identified in scientific studies as an area of high climate change risk. This is because increased warming, rainfall, wildfires and extreme weather events have already been observed, with increasingly negative impacts on local people, ecosystems and economies.

The municipality is adapting to the effects of climate change by implementing the uMngeni Resilience Project, in partnership with the University of KwaZulu-Natal School of Agriculture, Earth and Environmental Sciences, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Fire Protection Associations, Working on Fire and Department of Environmental Affairs.

A fire early warning system in Nhlazuka is one of the resilience measures being put in place during a five-year, multi-component project supported by the Adaptation Fund, a global initiative that finances climate adaptation projects in developing countries.

“There is no doubt that climate change is real and that it is happening,” says uMgungundlovu mayor Thobekile Maphumulo. “Last year our municipality, along with many other parts of South Africa, faced a severe drought that we are still recovering from.”

“We have seen an increase in sudden and severe high-intensity weather events, such as storms, lightning and flooding, that risk human life and cause damage to the environment, infrastructure and people’s homes.”

“We have seen an increase in sudden and severe high-intensity weather events, such as storms, lightning and flooding, that risk human life and cause damage to the environment, infrastructure and people’s homes.”

The uMngeni Resilience Project responds to the anticipated changes in climate in the uMgungundlovu district by reducing climate vulnerability and increasing the adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities and small-scale farmers.

“Climate change and all that it brings with it – droughts that threaten food security, cause job losses in the agricultural sector and affect availability of water; storms and flooding that threaten human lives and homes – is likely to make poverty, inequality and unemployment worse.

“It is vital that we work with communities, particularly those that are most vulnerable, to build their resilience so that when the worst comes, the impacts will be less, they will be able to rebuild quicker and emerge stronger and more self-sufficient,” Maphumulo says.

FireHawk Down

In 1994 commercial farmers and the timber industry joined forces to install FireHawk, the first computer-assisted fire detection system in the world, in the Richmond local municipality. Nhlazuka is a ward of Richmond, about 80km away, and the municipality plans to deploy the FireHawk system as part of the uMngeni Resilience Project.

FireHawk consists of 360-degree rotating cameras mounted on a 27m-high tower overlooking the area. The cameras stream images to the FireHawk detection center, where a bank of computers are monitored 24/7 by operators working three eight-hour shifts a day.

When the cameras detect smoke or a potential fire, the computers help the operator to zoom into the site and watch it live, to determine the direction of the fire, how far away it is and how threatening it is. Once it is confirmed that a fire is threatening, it is then positioned on a map to show its exact location.

When the cameras detect smoke or a potential fire, the computers help the operator to zoom into the site and watch it live, to determine the direction of the fire, how far away it is and how threatening it is. Once it is confirmed that a fire is threatening, it is then positioned on a map to show its exact location.

The FireHawk system has a cross-referencing feature which provides 99.9 percent accuracy of the location of the fire. Once the operator positions the location of the fire on the map, he then selects another camera with a clear view of the fire. There are two cameras looking at the fire from two different angles, enabling the operator to determine the distance of the fire from farms and homes.

The operator’s duty is to notify the owner of the property where the fire has been located. If it is a threat, firefighting personnel and vehicles are quickly dispatched from the Richmond incident command center based next to the FireHawk detection center.

The Richmond FireHawk system detects an average of 350 wildfires a year, although each season is different. The most wildfires detected in one season was five years ago, with 540 fires.

Last year was the best season, with the detection of 84 wildfires. Terry Tedder, who has worked at the Richmond Fire Protection Association since 2007, says increased education in fire prevention and management methods is helping to reduce the number of wildfire incidents.

The FireHawk team aims to erect a 30m camera tower system in Nhlazuka at the Thusong community center, which has an eagle’s-eye view over the community. The early warning system should be piloted in 2018, and the dream is to have a Working on Fire team stationed at the center, says Tedder.

“Detection is not enough, we need a team to extinguish the fires close to the community. It takes about an hour to drive from the main town of Richmond to Nhlazuka, so even if a fire is detected early it may be too late by the time a firefighting team arrives to assist,” says Tedder.

Mayor Maphumulo says the FireHawk early warning system needs to be part of a holistic fire-fighting approach in Nhlazuka: “We won’t just focus on sending out warnings, but will work with the communities to develop local fire management and response plans so that everyone knows how to respond to the different types of warnings. This system will help us to avoid loss of life and property from veld and forest fires.”

Tedder says the Richmond FireHawk system covers an area of about 240,000 hectares (925 square miles) and is funded by members in the timber and commercial farming industries.

Until now its protection did not include the 17,000 to 20,000 hectares of community land owned by the Ingonyama Trust in uMgungundlovu municipality, including Nhlazuka. The trust is the registered owner of large tracts of land in KwaZulu-Natal that have historically been part of the Zulu kingdom, dating back to various Zulu kings.

“The biggest challenge fire protection associations face is the issue of costs of firefighting staff and equipment. Commercial farmers can afford the equipment to help with the prevention and management of fire, but rural areas cannot, making them not self-sufficient,” says Tedder.

FireWise Interventions

Bono Cwazibe, who grew up in Nhlazuka, is the local supervisor of a national government initiative called the FireWise Communities Programme. His job involves door-to-door education on preventative fire methods and assisting in the clearing of fire-fueling alien plants.

Bono and the community do not fully understand climate change and its global impacts, but he believes the resilience project is part of the uMgungundlovu municipality’s goal of educating the community about climate change.

Since the implementation of FireWise in 2014, he says, the number of fires in the Nhlazuka area have decreased. It takes on average five hours to put out a fire once it has spread and to date, there is only one known death due to fire that occurred in 2013.

Since the implementation of FireWise in 2014, he says, the number of fires in the Nhlazuka area have decreased. It takes on average five hours to put out a fire once it has spread and to date, there is only one known death due to fire that occurred in 2013.

In the past four years, the residents of Nhlazuka began receiving municipal water facilities and electricity. Receiving electricity has reduced the number of fires as people no longer need to cook on open fires – disposing of ash and strong wind speeds easily carried the sparks.

Another intervention has seen more than 70 percent of the thatched roofs replaced by tin roofs. This doesn’t solve the problem completely, however, as most of the homes are built with timber structures and once alight, the entire house can burn down.

Carrying her three-month-old granddaughter on her back, Shongaziph Ngcongo (44) says her thatched roof was replaced with a tin one after her home burnt down and this has helped her to feel safer.

“We would be happy to have a way to detect fires early,” she says. “This is important, because then we can take precautionary measures and protect ourselves. Wildfires affect us. They damage our belongings and our fields.”

Originally published at oxpeckers.org

This investigation by #ClimaTracker and Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism was produced in partnership with Code for Africa, and funded by ImpactAfrica and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation