This September a Louisiana judge derailed Formosa Plastic’s Sunshine Project, the largest industrial development ever proposed in the state’s heavily developed “Cancer Alley” region, where more than 200 industrial facilities already crowd the banks of the Mississippi River.

The ruling found that the plastics complex would emit so much soot that it would further endanger nearby communities — reason enough to cancel its previously approved air-pollution permits.

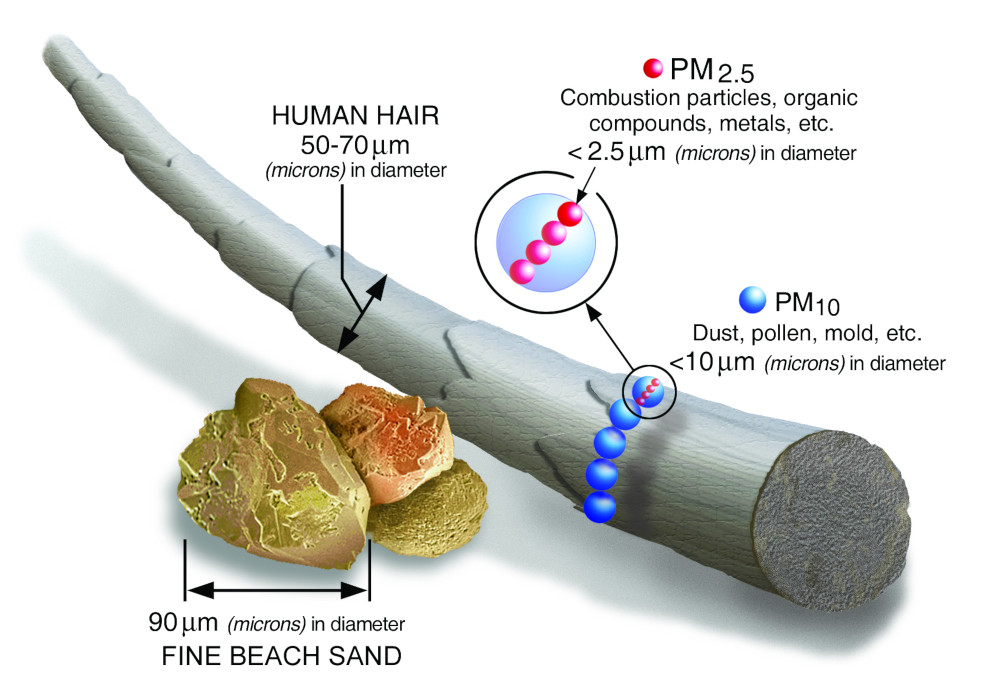

Louisiana citizens, who already suffer health problems from high pollution levels, had fought Formosa’s plans for years. While their court victory may sound like a David vs. Goliath story, the soot at the heart of the Sunshine ruling — tiny particles less than 1/30th the diameter of a human hair — still cause sickness and death nationwide, especially in low-income communities.

This madness must stop!

In Cancer Alley, Louisiana.Stop Petrochemicals! ✊🏾 pic.twitter.com/4Gnu0iCdNq

— rev yearwood ✊🏾 (@RevYearwood) November 15, 2021

Experts say addressing the threats of soot pollution on a national level is long overdue.

“Particulate pollution can cause lung cancer, asthma and other diseases,” says Gianna St. Julien, clinical research coordinator at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in New Orleans, which joined the case against Formosa.

The pollutant’s size is the problem, St. Julien explains.

When inhaled, soot measuring 2.5 microns and smaller — officially known as particulate matter 2.5 — can penetrate the lungs and enter the bloodstream, where it can cause stroke, heart disease, reproductive complications and much more.

While natural sources of PM2.5 such as pollen, dust and ocean spray have remained steady over time, the particles from burning fossil fuels and other industrial activities have risen sharply in recent decades, driving health concerns. Recent research estimates that PM2.5 causes 4.2 million deaths each year worldwide, including 50,000 in the United States.

In her September decision against Formosa, Judge Trudy M. White wrote that PM2.5 emission estimates provided by the company — and permitted by Louisiana’s environment agency — would violate the Clean Air Act and compound health risks already faced by communities in Cancer Alley.

Judge White also faulted the state for inadequately analyzing environmental justice impacts from the proposed plant, which would be built in a part of St. James Parish that is 87% African American. Residents include descendants of emancipated plantation slaves who in the 1800s purchased and worked the land so future generations could inherit “untainted” agricultural lands. To some, these lands are sacred.

These are important points to St. Julien, who in January co-authored research linking high cancer rates in Louisiana’s poor neighborhoods and communities of color with high exposure to pollutants like PM2.5.

Her research adds to a large body of work showing poor and minority communities across the country bear an outsized burden from air pollution. St. Julien and others attribute the disparity to decades of housing, zoning and other policies that make it easy for polluters to move into disadvantaged communities.

“Wealthier White communities are able to fend off proposals like Formosa’s more successfully because they have greater financial resources and political access,” says St. Julien. Additional Tulane clinic research published in 2020 supports the claim.

St. Julien applauds the Formosa decision but says more work is needed, especially in understanding the cumulative impact of the “cocktail of chemicals” breathed by residents near industrial sites. Additionally, she points out, the EPA monitors that track PM2.5 and other contaminants have historically been positioned away from the communities experiencing the worst air pollution, which puts residents at a further disadvantage.

“That’s why we did this study,” she says, “so residents already fighting for their lives wouldn’t have the added burden of trying to prove they’re impacted by these pollutants.”

The work by St. Julien and others is having an effect. Earlier this year, after visiting St. James Parish and other Cancer Alley neighborhoods, EPA chief Michael Regan announced plans to deploy mobile air-quality monitors to the communities.

A Lagging Regulatory Atmosphere

While Louisianans resist new polluters, others are taking the fight against PM2.5 to the national level.

For years scientists have warned that national standards under the Clean Air Act provide inadequate public health protections. Last year Harvard researchers connected thousands of premature deaths in the U.S. to coal, biomass, natural gas and other energy-related combustion sources, while a 2022 Health Effects Institute report found that exposure to PM2.5 concentrations below current standards causes mortality in older Americans.

The Clean Air Act requires EPA to revisit its standards every five years to ensure they keep pace with science. But the last change came back in 2012, when the Obama EPA lowered the acceptable limit of ambient PM2.5 from 15 to 12 micrograms per cubic meter.

In 2019, after the Trump administration took office, EPA scientists recommended lowering the standard again, saying that a range of 8-10 micrograms could save up to 12,000 lives each year.

“But the Trump administration blasted forward with their review,” says Seth Johnson, a senior attorney with Earthjustice. Ultimately, the Trump administration declined to toughen standards.

Coal industry backers lauded the Trump decision. Earthjustice, meanwhile, sued the EPA on behalf of a coalition of groups that included the American Lung Association and Union of Concerned Scientists.

“All these groups said the science shows that people die at current PM2.5 standards,” says Johnson.

Soon after the Biden administration took office, the new EPA leadership announced a course change and in 2022 published a supplement to the scientific reports used under Trump. It further supported strengthening PM2.5 standards, which the Biden EPA hopes to finalize next year. The administration has also proposed new rules to reduce PM2.5 and other pollutants from heavy duty trucks beginning in the 2027 model year.

To Johnson, addressing both transportation and stationary sources such as power plants will help attain lower PM2.5 levels.

Johnson also sees the environmental justice angle highlighted by St. Julien.

“It’s a really big deal,” he says, noting that the Clean Air Act is supposed to protect outdoor air for all groups, but that it obviously falls short for certain communities. But Johnson says he sees building awareness of the dangerous inequality.

The Biden administration also sees the problem. A 2022 policy assessment conducted as part of the current PM2.5 changes acknowledges strong evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in PM2.5 exposure, EPA spokesman Tim Carroll says by email. He added that in 2022 EPA identified strategies to ensure PM2.5 standards are met in communities with low socio-economic status.

Meanwhile a new source of soot has emerged.

The Climate Wild Card

Over its 52-year history, the Clean Air Act has had a remarkable record of reducing particulate pollution. As the EPA tracked the science through the five-year reviews required by the law, it went from only regulating particulates of 25-40 microns in the 1970s to then including 10-micron pollutants (PM10) in the 1980s and eventually PM2.5 in the 1990s. It has also gradually lowered the PM2.5 threshold. As a result, EPA estimates, we’ve seen a 37% decrease in ambient PM2.5 in the past two decades.

But today scientists warn that wildfire smoke tied to climate change is erasing the gains.

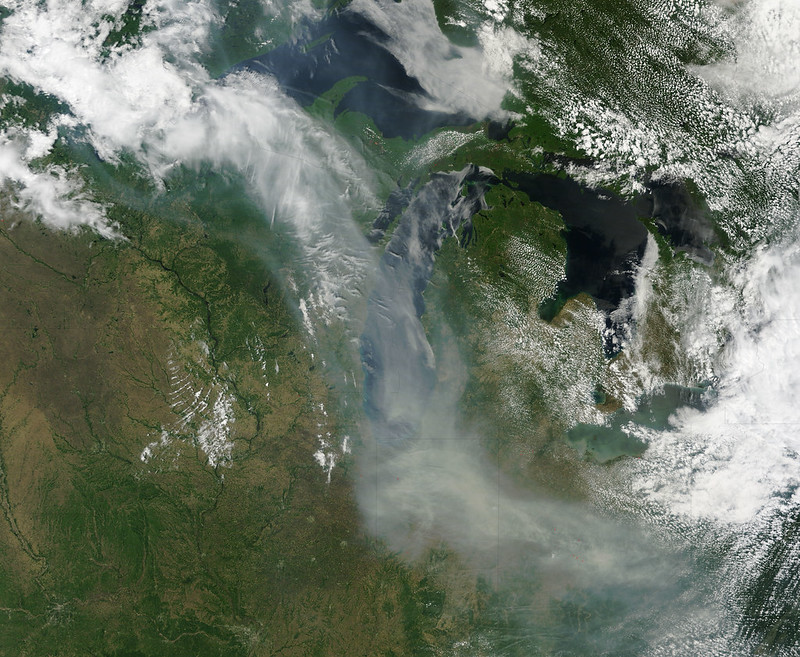

In September researchers at Stanford University showed millions of Americans now experience extreme levels of PM2.5 across areas affected by wildfire smoke, which can drift thousands of miles.

“We observed enormous increases in the number of days with smoke and the number of days with extreme smoke,” says Marissa Childs, who contributed to the study as a Ph.D. student at Stanford and is now a fellow at the Harvard University Center for the Environment.

The researchers used satellite imagery from 2006 to 2020 to track drifting smoke, which they then correlated with spikes in PM2.5 detected by regional EPA air monitors. They used artificial intelligence techniques to apply the results over the broad areas between air monitors across the contiguous 48 states.

The work showed that swaths of Americans now experience at least 100 micrograms of PM2.5 every year, many times above the current standard and a 27-fold increase over the last decade. It also showed a whopping 11,000-fold increase in people experiencing days of at least 200 micrograms of PM2.5, which Childs says used to be exceedingly rare.

“It’s really bad,” she says, pointing out that particulate matter from smoke poses many of the same health dangers as other pollutants.

But Childs says the soot from these events are “completely unregulated” because they fall under the Clean Air Act’s Exceptional Events Rule, which exempts rare or unique emission sources such as fires. But the events are becoming more common, she says, as wildfires increase in severity, duration and the number of acres burned.

A spate of recent research agrees. UCLA researchers found that a combination of wildfires and increasingly hot and stagnant air patterns raises levels of PM2.5 and ground-level ozone in Los Angeles, Denver and other cities. The findings come as residents of Seattle and Portland, Oregon, have breathed record wildfire smoke in recent years.

The Stanford work found the increase in smoke-related PM2.5 affects wealthier populations and communities that census data show are predominantly Hispanic, which they attributed to demographics in western and southwestern regions.

Childs also recognizes that the effects may be disproportionately felt in disadvantaged communities, where the added PM2.5 comes atop already high pollution levels.

Research also shows that PM2.5 and larger particles interact with climate change in complex ways. Scientists have long shown that black carbon, which can be included in PM2.5, accelerates melting of glaciers and sea ice around the world, contributing to climate tipping points. As soot from wildfires settles to the ground, it also accelerates snowmelt in the West’s mountainous areas, compounding droughts tied to climate change.

And just as St. Julien and others have noted for PM2.5 pollution, the effects of climate change are also known to put the heaviest burden on disadvantaged communities.

For St. Julien, the EPA’s reconsideration of its PM2.5 standards are an overall step in the right direction.

But that’s not enough, she cautions. More work is also needed to protect frontline communities and ensure that states comply with EPA standards in the first place.

In the case against Formosa, the courts agree.

Previously in The Revelator:

Collision Course: Will the Plastics Treaty Slow the Plastics Rush?