Oh what a difference a few decades make.

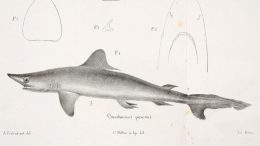

Back in in the 1980s and 1990s, a species known as the smalltail shark (Carcharhinus porosus) was one of the most common fish caught off the coast of northern Brazil.

That’s not the case anymore. A new paper by researchers from a trio of Brazilian science institutions calculates that smalltail shark populations in the country have declined by a shocking 90%. They say the species has now become critically endangered and is in need of “urgent conservation methods…to prevent its extinction in the near future.”

The problem, as with so many other declining oceanic species, stems from rampant overfishing.

In this case smalltail sharks face similar threats from two very different types of fisheries. Small-scale, artisanal fishers use gillnets to catch species like mackerel and weakfish, while industrial-fishing operations use trawl nets to catch shrimp and massive gillnets to scoop up catfish and other bottom-dwelling species. These industrial gillnets regularly reach up to 5.5 miles in length.

Each of these methods indiscriminately catches a wide range of species, including smalltail sharks, which swim in muddy coastal waters and estuaries. The sharks only reach 3-4 feet in length, so they’re easily swept up by these fishing operations.

Amplifying the fishing threat, the paper reports, a majority of smalltail sharks caught by the fisheries have always been juveniles. In the 1980s sharks younger than six years accounted for 90.6% of catches.

The elimination of so many immature sharks from the population removed any chance they’d get to breeding age and perpetuate the species.

Brazil recognized the threats to these sharks a few years ago and declared them critically endangered in their waters. But the IUCN Red List still identifies the species as “data deficient,” meaning its extinction risk hasn’t been fully assessed on a global level.

To solve that, the paper also takes a deep dive into the shark’s biology and comes up with some startling revelations. Among them, the authors upend previous research suggesting the species had a fast growth rate and reveal that it actually “has one of the longest juvenile phases when compared to several species of small coastal sharks, thus taking longer to reach sexual maturity.” This makes the smalltail shark an “intrinsically low-resilient species” that is “highly vulnerable to fishing exploitation.”

Meanwhile a second study by some of the same authors looked at the sharks from a different angle: microchemistry. The researchers examined vertebrae from 17 sharks caught in the 1980s and in the past couple of years to determine their elemental compositions. Based on the levels of barium, calcium, magnesium, manganese and strontium in the bones and at various sites around the country, the researchers hypothesize that northern Brazil holds at least three major birthing sites for the species and that the country’s waters serve as important habitat for smalltail sharks throughout their lifecycles.

The fisheries study focuses on the threats in Brazil, but the authors point out that these same fishing threats occur throughout the smalltail shark’s range. They’re calling for the animal to be considered critically endangered not just in Brazil but on a global level.

The paper points out what could happen if conservation action isn’t prioritized. Another species from the same genus, Carcharhinus obsolerus, was declared extinct in 2019. Dubbed the “lost shark” by the researchers who discovered the species from decades-old museum samples, the shark was probably also wiped out by overfishing — before it was ever scientifically recognized.

Without protection the smalltail shark could soon join its fellow among the ranks of the lost.

![]()