The Internet has revolutionized the way the world exchanges and consumes ideas, information and merchandise. However, it also has its drawbacks. The Internet has facilitated illegal trade in wildlife, which is having a devastating impact on animals, ecosystems and the communities who rely on them.

Online platforms provide easy opportunities for all kinds of criminal activity, including wildlife trafficking. One of the biggest challenges is distinguishing legal from illegal trade. Items for sale cannot be examined in person. Traders sometimes use code words to disguise illicit activity. And there is usually little, if any, supporting documentation to confirm that the trade is legitimate. This documentation should be in the form of certification under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), as well as national or provincial permits.

A big chunk of research into online illegal wildlife trade has been aimed at trying to determine if the Internet really is a conduit for illegal wildlife trade, by looking at the scale of impact increased access has had on animal trafficking. Gathering this data is a challenge. But though it is difficult, it is not impossible.

One of the ways to collect this data is to use the search function on commercial websites and social media platforms, using specific keywords. When it comes to the four commodities chosen as the focus for this series — pangolins, leopards, rhinos and sungazer lizards — relevant keywords include “trophy”, “skin”, “fur”, “dragon”, “pelt”, “tusk”, “ivory”, “scales”, “taxidermy”, “rug”, “hide”, “bone”, “meat”, “delicacy”, “medicine” and “live.”

It is more complicated than simply punching in a word and pressing “search.” Often traders will alter the description of what they are selling to evade easy detection. It helps to pay attention to alternative spelling, slang words and entirely misleading product descriptions.

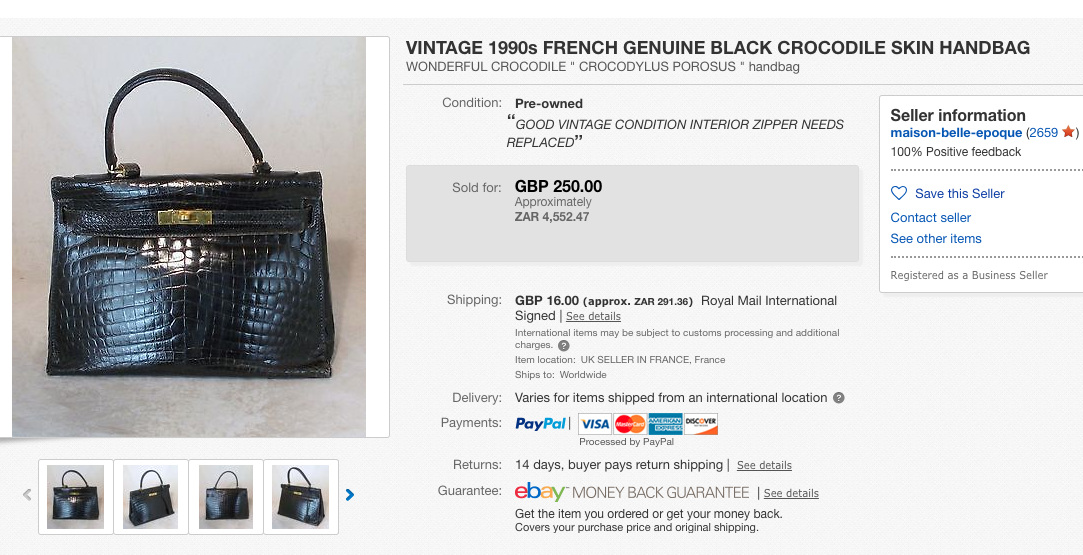

The beauty and the horror of online trade is that it distances the consumer from the trail of bloodshed that results in that “miracle cure,” new fur coat, ivory-coated trinkets for the mantelpiece, the “authentic” African bracelet picked up on safari, or that designer snakeskin handbag or pair of shoes.

A Million-dollar Marketplace

Most animals, their products and parts land up via online trade in Asia, Europe and the United States.

“The species offered for sale in each region or country varies greatly depending on the preferences of consumers,” according to a paper on wildlife cybercrime by Tania McCrea-Steele of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW).

For example, sungazer lizards are quite popular in the Middle East, where they are considered status symbols. In Asia pangolin meat is considered a delicacy, and their scales are widely used in Chinese medicine.

South African-based traders posted the most advertisements during IFAWS’s research for Wanted – Dead or Alive: 718 in total, offering nearly 8,500 wildlife specimens for sale. Most of these were parts and products, not live animals.

The most popular online marketplaces included eBay (45 percent), Gumtree (13 percent), Classifieds (12 percent), BidorBuy (8 percent) and OLX (5 percent). The most popular social media platforms were Facebook (33 posts), Instagram (17 posts) and Twitter (two posts).

Crocodile and alligator parts, often in the form of clothing and fashion accessories, were the most traded specimens online, with almost 7,000 in total. Ivory was next, with nearly 900 pieces advertised; there were also 161 live parrots, snakes (122 live specimens and 10 parts and products) and big cats, such as leopards, (56 live specimens and 39 parts and products).

The total value of the South African-based online wildlife market during the six-week IFAW investigation was $3.9 million, or R54 million.

Proof in the Pangolin

What is it that makes the Internet so attractive to sellers and buyers? Answering this question is difficult because, as described in “South Africa’s Wildlife Cryptotrade” (part one of this series), data collection is a significant challenge. This is especially so because it is easy to stay off the grid and remain anonymous.

Illegal traders don’t need to be hackers or to turn to the Dark Web (content that exists on “darknets,” which use the Internet but require specific software, configurations and authorizations to gain access) to sell and buy live animals, their parts and products.

Hard data collection aside, it is best to turn to the animals themselves to understand the issue. In just a decade, more than 7,300 rhinos have fallen victim to poaching (see PoachTracker). With more people being able to go online from anywhere in the world (as of January 2018, approximately 4 billion people have access to the Internet worldwide), there is no doubt that at least part of the trade process happens online. At the very least, products are advertised online, even if the actual exchange of money and/or the product takes place in person.

Most incidents of rhino poaching were by poachers looking to claim the horn and, according to conservation experts, the majority of these horns are sold on black markets in China and Vietnam. While many of these interactions are likely to take place in the back alleys and dark corners of the world, the process has to start somewhere: a buyer does not merely show up at the right place, at the right time without first knowing how, when and where a sale will take place.

Pangolins are the most trafficked mammal in the world, and in 2017 approximately 15 tons of pangolin scales were recorded to have been placed on the market. In both Africa and parts of Asia, their scales are said to cure a multitude of ailments, as part of traditional medicine.

Although a ban on global trade of all pangolin species was introduced in 2016, the demand for these mammals has not declined significantly enough for them no longer to be considered endangered. These animals are sometimes advertised under “anteater scales” across social media.

Endangered Species

Sungazer lizards are endemic to Highveld grasslands in South Africa, and are classified as “vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List of endangered species. Adverts on social media indicate part of their popularity is due to their dragon-like appearance — their biological name, Smaug giganteus, comes from the dragon in JRR Tolkien’s book The Hobbit.

Leopards are listed under Appendix I of CITES because they are vulnerable to extinction, and trade in their parts and products is only permitted under “exceptional” circumstances. However, a quick search reveals dozens of advertisements for “real” leopard-skin products.

It is unclear how many of these are legitimate; in many instances, sellers are simply referring to the pattern of a product, as opposed to the actual material. That being said, at least some of the products advertised are real, as indicated by the rate at which this species is being wiped out across the country. As with the other commodities, it is likely that at least part of the sales interaction takes place online.

This is the second of a six-part series on online illegal wildlife trade featured by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. Research was funded by the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, and support was provided by the Endangered Wildlife Trust, TRAFFIC and the International Fund for Animal Welfare.