One day in the middle of June, heavy rains drenched Albuquerque while lightning lit up the barren mesa outlying the city. It was the rainiest June 16 on record for the New Mexico city, with almost an inch measured over the course of the day. But the precipitation didn’t do much to ease the region’s longstanding drought or recharge the dwindling flow of the once-mighty Rio Grande River.

Right now 90 percent of New Mexico is considered to be in severe to exceptional drought. Conditions are symptomatic of a growing — and troubling — trend of drying in the Southwest, where average annual temperatures have ticked upward by two degrees. The region has become increasingly prone to wildfire, and water is strictly managed, making farming everything from the state’s iconic green chile to southern New Mexico’s pistachios riskier than ever.

The effects of these changes on the climate are on full display in the Rio Grande, one of the largest and most heavily managed rivers in the United States, which spans 1,900 miles through largely arid and desert lands. This year the river is already dry along a 20-mile stretch south of Albuquerque. While the river has run dry for even 90-mile expanses in the past, what’s exceptional about current conditions is just how early the drying is happening — beginning in the first week of April instead of the typical mid-June. By summer’s end this year, 120 miles are expected run dry, exposing the sandy underbelly of the iconic, once-thriving watercourse.

This water shortage, experts say, has implications not just for humans but also for species of flora and fauna that depend upon the Rio Grande.

For one species, an increasingly dry riverbed could threaten its very existence.

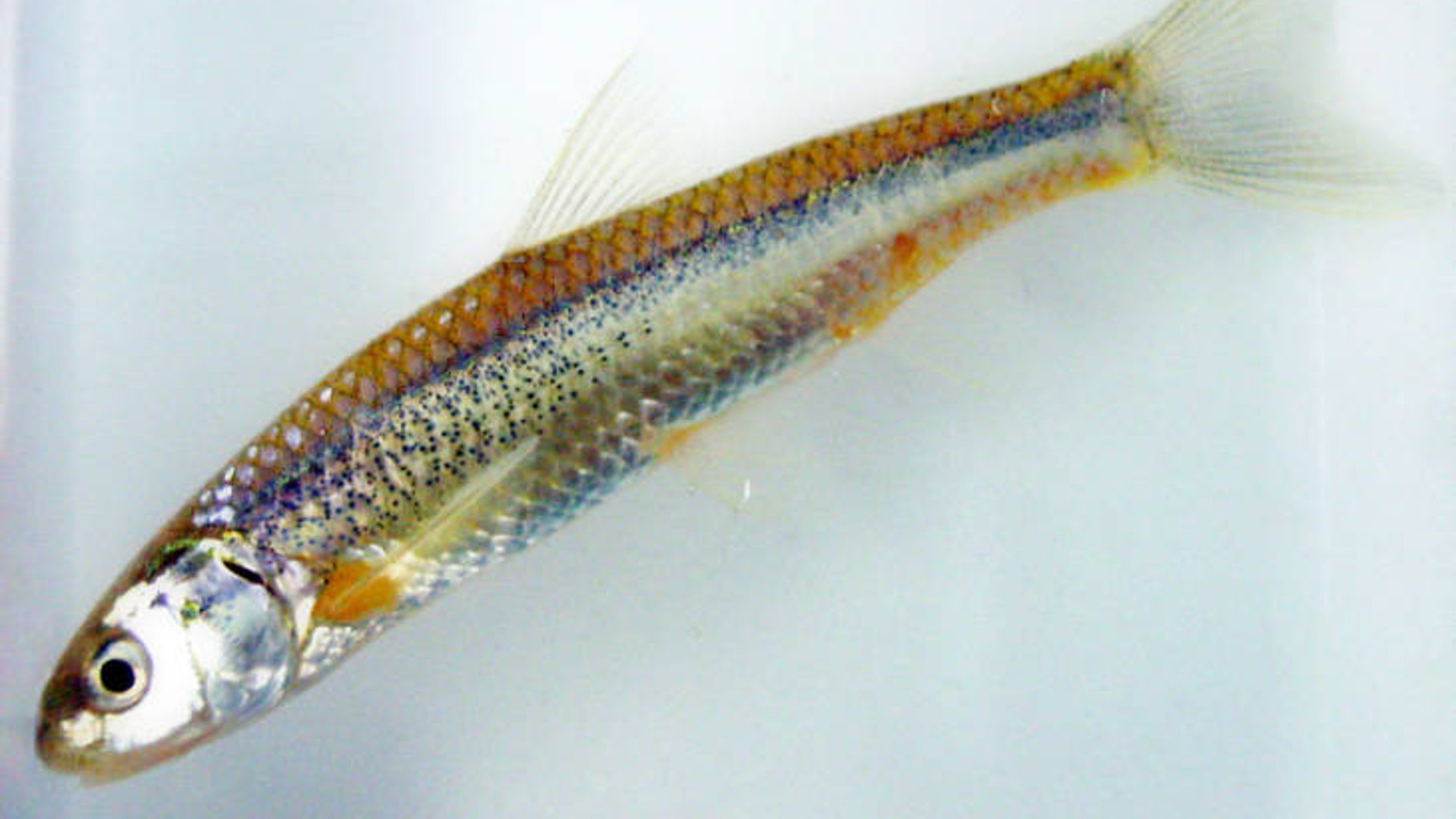

The Rio Grande silvery minnow (Hybognathus amarus) has the distinction of being one of the most endangered species in the country. The small, short-lived fish began its decline in the 1960s following the advent of significant damming of the river. The population continued to suffer as the result of the introduction of non-native fish species, warming river temperatures and decreased annual precipitation. In addition to dams, the river’s ecosystem has been altered significantly over the past 100 years, and the strong flows that spur spawning and shallow eddies that support the silvery minnow during the rest of its life cycle have all but disappeared.

The consequences of drought for the species can be grave given their already abbreviated lifespans.

“Most silvery minnow die before age two,” explains Thomas Archdeacon, a fish biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who works on restoration and rescue efforts for the species. “The bulk of the population is usually made up of the youngest fish at any given time, so if you have a year of failed reproduction, the minnow can quickly go from the most common fish in the river to one of the least common.”

For the silvery minnow, sustained drought makes survival — let alone procreating — more difficult. “In a year like 2018,” Archdeacon says, “not only are the fish stressed early in the year, the adults are dying before spawning.” He points out that even in the reaches of the river that haven’t dried, water temperatures are climbing and flows are steadily dwindling, impacting the health of the fish and the likelihood that they will reproduce.

This follows trends seen in previous years. The success of fish’s population hinges largely on the spring hydrograph. “When there is poor snowpack,” Archdeacon says, “there is generally a year of failed reproduction.”

And so, in years like this, crews led by the New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office muddy their shoes in the river, recovering stranded fish from pockets that have experienced severe drying and transferring them to more reliably full parts of the river. This year the first silvery minnows were rescued on April 2, the earliest recorded date that salvaging has taken place in the past 19 years.

Unfortunately, preliminary evidence suggests that many of the fish trapped, then released in areas of the river with perennial flow do not survive.

The office also heads up another important effort: the release of hatchery fish to boost the wild population. Each year thousands of captive-hatched fish are returned to the river, with well over a million having been released since the program started. “The number released each year scales with how good or poor the fish’s natural reproduction was,” Archdeacon explains. So once the river recovers in late fall — typically November — a large but as-yet undetermined number of hatchery fish will likely be released.

“Both these management options are reactive and not proactive,” Archdeacon says, meaning they’re more of a Band-Aid than a solution. And even though more than $150 million has been spent on such efforts since the fish was placed on the endangered species list in 1994, it’s hard to say at this point if the conservation budget for the fish will keep up with emerging climate-related threats. Archdeacon declined to comment on any future budgets for the silvery minnow.

What is certain, Archdeacon says, is that “it’s hard to get away from the reactive, labor-intensive management of the species if spring runoff continues to be poor.” In this increasingly warm part of the country, the outlook for the river — and the fish and other species that depend on it — isn’t too promising.

Broad, intensive efforts over the past two decades prevented the silvery minnow from becoming even more endangered, but as Archdeacon looks to the future he has a dire prediction for next year and beyond. “If there is a poor year again in 2019,” he says, “the clock will have reset and all progress erased.”

© 2018 Maggie Grimason. All rights reserved.