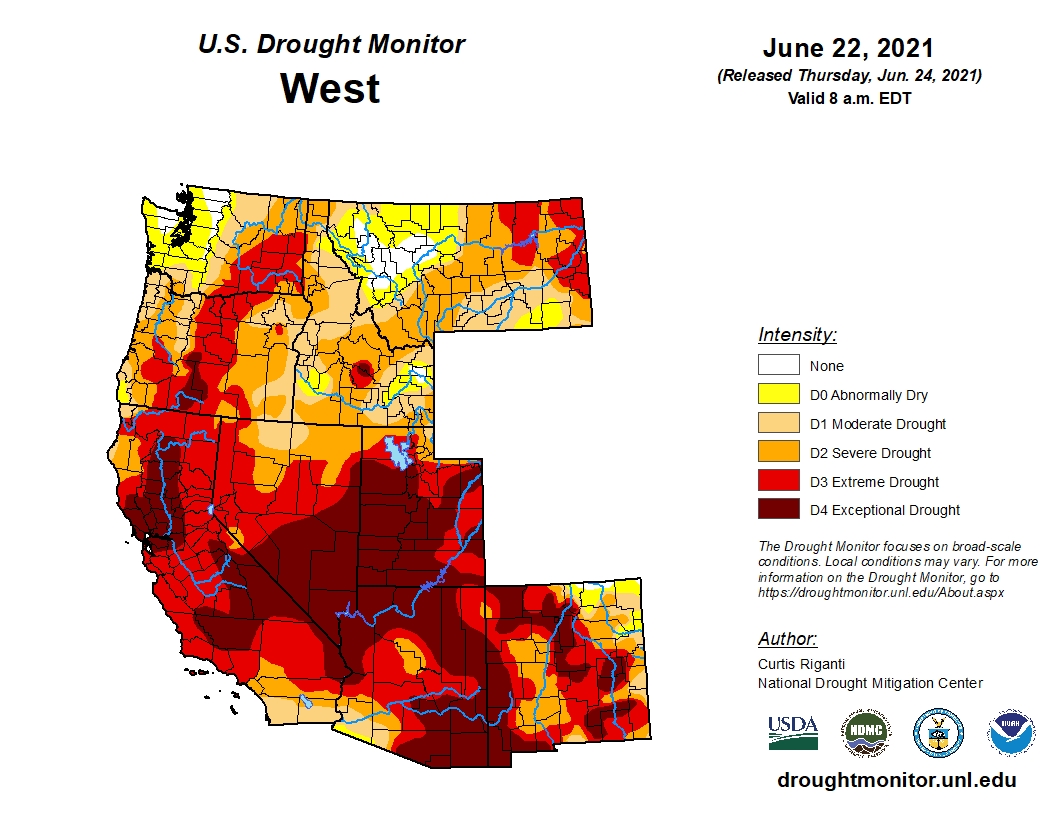

Extreme drought conditions gripping the West have stirred familiar struggles over water in the Klamath Basin, which straddles the Oregon-California border. Even in a good year, there’s often not enough water to keep ecosystems healthy and farms green — and this year is anything but good.

For the past two decades critics have simplistically reduced water woes in the basin to “fish vs. farms” in the battle for an increasingly scarce resource. This year, which is expected to be the lowest water year on record, it’s clear there aren’t any winners.

The Bureau of Reclamation, a Department of the Interior agency that oversees water resources in the West, has already shut the tap on irrigation water for farms in the area in order to maintain water levels in Klamath Lake needed to protect endangered suckers. It also halted releases into the Klamath River that help keep fish healthy. Following that, high temperatures and low flows fed an outbreak of the parasite Ceratonova shasta, causing a massive die-off of hundreds of thousands of juvenile salmon this past spring.

And another dire casualty hovers in the wings — birds.

Millions of birds migrate through the basin each year, relying on a complex of wildlife refuges that are quickly running dry. Last year drought conditions forced too many birds into too small a space, and 60,000 perished of avian botulism that spread quickly in close quarters.

Experts predict this year will be worse, and the problems could extend south to California’s Central Valley. Both places are critical stops on the Pacific Flyway, used by more than 320 bird species to feed and rest as they travel up and down the west coasts of North and South America.

Both the Klamath Basin and Central Valley will have limited water this year.

“We’re really concerned for what’s going to happen this fall and winter when birds are coming through the Central Valley and other drought-stricken parts of the Pacific Flyway, like the Klamath where habitat is extremely limited,” says Rachel Zwillinger, water policy advisor for Defenders of Wildlife. Water-supply reductions are creating concerns about inadequate food supplies and overcrowding on the small remaining areas of habitat.

“And then once you start to see that overcrowding, it creates serious concerns about outbreaks of disease,” she says.

Adding to the tragedy is that this is largely a crisis of our own making.

The Big Dry

At the turn of 19th century, 350,000 acres of wetlands, lakes and marshes stretched across the Klamath Basin. Two years later President Theodore Roosevelt signed the National Reclamation Act, and the agency now known as the Bureau of Reclamation began draining water, building canals, and converting soggy ground into something firm and farmable.

In all, about 80% of the historic wetlands dried up. The diverted water fed the Klamath Project, which the agency uses to supply irrigation water to farms. In one concession to nature Roosevelt created the country’s first waterfowl refuge at Lower Klamath Lake. Five more wildlife refuges in the basin were added over the years, but only two still contain critical wetland habitat today: Lower Klamath and Tule Lake National Wildlife refuges.

Unfortunately those remaining wetlands were cut off from natural water flows and weren’t allotted their own dedicated supply of water. Instead the refuges rely on agricultural runoff or excess water supplied by Klamath Project farmers.

Since the Bureau of Reclamation has shut off irrigation water for those famers this year, runoff flowing to the refuges will be vastly reduced, and there’s little chance of surplus becoming available later.

Jeff Volberg, director of water law and policy for California Waterfowl, fears more disease outbreaks of avian botulism will be on the way.

“The only way to stop that outbreak is with more water to flush the system and by getting out there and collecting dead and injured birds as quickly as possible,” says Meghan Hertel, director of land and water conservation for Audubon California, who was at the refuge last year during that grisly process.

And there are other concerns. In 2020, also a drought year, ducklings born at the refuges were stranded away from the water as the wetlands dried up over the season.

“You’d have ducklings walking a couple of miles to get to water,” says Volberg. “You lose a lot of ducks that way.”

Some birds also molt while at the refuge and remain grounded until they regrow their flight feathers. Leaving to find areas with more water isn’t an option for them. That leads to more crowding and more disease.

“It’s a perfect storm of everything going wrong,” he says. “You’re taking this historically huge lake and marsh complex and turning it into a desert. It’s a very tragic circumstance.”

More of the Same

California has a history of reclamation akin to Oregon’s.

The Central Valley used to be a vast network of wetlands with rivers that overtopped their banks in winter and recharged the marshes. “But once we dammed the rivers and created levies, we cut off the historic wetlands from their water sources,” says Zwillinger.

Today the Central Valley is the agricultural heart of the state, but just 5% of the historic wetlands there remain. Unlike in Oregon, federal, state and private refuges in the valley have a guaranteed entitlement to water under the Central Valley Improvement Project Act, passed in 1992.

The remaining wetlands are now managed much the way a farm would be, except the food grown is for birds.

“It’s very strategic when we put water on the landscape and when we take it off,” says Ric Ortega, the general manager of the Grassland Water District, which solely delivers water for habitat purposes for Central Valley refuges.

“We’re trying to germinate specific grasses that are high in amino acids and protein, but that are also readily decomposable, which causes an invertebrate bloom,” he says. “So there’s actually a fair amount of planning.”

This year the planning will be extra tough.

Although the wetlands have a guaranteed water supply, they’re not guaranteed to get all of it. Five of the region’s 19 refuges still lack the physical infrastructure necessary to deliver water.

The others can also see cutbacks.

In years when flows into Lake Shasta in Northern California fall below a critical threshold, the federal government can short the refuges 25% of what’s known as their “level 2” water supply, which makes up about two thirds of their total allocation. The other third, known as “level 4,” is acquired by the Bureau of Reclamation from willing sellers on the open market.

This year the refuges will be shorted their 25%, and Ortega says they’re anticipating that Reclamation won’t be able to provide much, if any, of their level 4 supply either. He estimates that they’ll have only half their contracted water supply.

If you add that to the historic deficit, the picture is grim.

“In years like this, you can think of only 2.5% of historic wetlands being available for these 10 million birds that are coming our way, whether we like it or not,” says Ortega. “The boreal and the Canadian prairies are healthy and have been for the last couple of years. So we’re expecting lots of birds, a large hatch, to come in. The stars are aligning in a bad way.”

Managing for Shortage

In anticipation of that surge, refuge managers in the Central Valley will operate much like farmers and allow some of the land to go fallow.

“What that does is it not only shrinks the wetted footprint of the wetland habitat spatially, but it also shrinks that in time,” says Ortega. Being able to put less water on the land means it will also go dry more quickly.

“It’s an especially constraining and difficult situation given the Klamath is dry, so there’s really no stopover site there,” he says.

Early migrants may start to arrive in July, but the largest numbers congregate in late November and early December. Typically wetland managers in the region would begin putting water on the landscape in mid- to-late August and have it fully inundated by the end of September or early October.

“For this year, we will probably start putting water on the landscape in a big way in October,” says Ortega. “We have to be strategic about when we flood and ensure that we’ve got adequate water to maintain that footprint through the overwintering period. Ideally we can maintain it into late March and April. But that may not be in the cards if the winter is dry.”

Even if most birds won’t arrive for months, a lack of water in the summer also means that there’s likely to be inadequate food for hungry travelers later in the year. And because there are so few wetlands remaining, birds use agricultural land as surrogate habitat, says Hertel.

That’s especially true at in the Sacramento Valley, at the north end of the Central Valley. Waterfowl get about half of their diet from the area’s rice fields in the fall and winter. After harvest, rice farmers usually flood their fields to help with decomposition of the rice stalks, which attracts insects and creates food for birds.

But this year water cutbacks mean that rice farmers will likely use all their water to grow rice, or will sell it to other eager buyers, and won’t have any to flood fields later in the year. About 100,000 acres are also likely to be fallowed — another hit for migratory birds.

“If it doesn’t rain, that’s 50% of ducks’ diet gone in fall and winter,” says Hertel.

And it’s not just birds who rely on the refuges.

“These places are incredibly diverse,” says Ortega. In the Central Valley that includes minks, river otters, beavers, Tule elk, deer, bobcats, mountain lions and 300 species of bird. The wetlands also support threatened and endangered species like the giant garter snake, tri-colored blackbirds and western pond turtles. In the Klamath Basin, the area is also home to the largest wintering population of bald eagles in the lower 48.

Finding Solutions

With a potential crisis looming, what’s to be done?

Unfortunately there are no easy solutions when it comes to water in the West. Increasingly hot and dry conditions spurred by climate change — also a crisis of our own making — puts pressure on water systems that are already strained.

For the past century we’ve watered farms and grown cities while pulling more and more water out of watersheds. The bill for that is now coming due.

“In the Klamath, the system is overextended,” says Hertel. “You have tribes with very valid concerns about fish extinction — fish that are essential and core to their community and way of life. You have farmers who have had farms up there for 100 years who are going out of business and are worried about their families and their communities. And then you have the refuge, which is supposed to be this jewel of our Pacific Flyway system, receiving very little water and having massive die-offs.”

It’s a similar situation in California with thirsty farms, expanding cities, overtaxed watersheds and endangered species in the Delta — the linchpin of the state’s water-conveyance system.

But experts say there are both short and long-term solutions that could help. The first would be to get water to the refuges as quickly as possible.

In the Klamath, Volberg says, “We feel the most appropriate thing would be for the refuge to have its own dedicated supply from outside of the basin.” California Waterfowl has been raising money from private funders to buy water rights from willing sellers upstream. They’re hoping to acquire 30,000 acre-feet of water rights that upstream irrigators would leave in the river for the refuge downstream. “That would only really provide about one third of the water that the refuge really needs, but it’s a whole lot better than no water at all,” he says.

Buying the water is just the first hurdle. They’re awaiting approval for the water rights transfer from the Oregon Department of Water Resources. If that comes through, they’ll then need Reclamation to open the headgates to allow the water out of the river. That part may be trickier.

A certain level of water must remain in the top part of the system, Upper Klamath Lake, to protect two species of endangered suckers important to the Klamath Tribes. And water is needed downstream in the Klamath River to also protect endangered salmon vital to tribes such as the Yurok, Hoopa Valley and Karuk.

There’s also the other matter of anti-federalists threatening to forcibly turn on irrigation water for farmers.

Despite all that, Volberg hopes they’ll be able to pull off the water transfer this year and in the long run work with state and federal agencies to secure that 30,000 acre-feet permanently. But that will come with a price tag of $50 to $60 million, he says.

In the Central Valley, Ortega says federal and state resources are welcome, too. And the money can be used to stretch limited resources further. “We can rehabilitate groundwater wells and lift pumps and develop recirculation systems and do better monitoring,” he says.

Hertel says we’ll also need policy and infrastructure that can better help us manage limited water supplies in the future.

“This isn’t just a drought,” she says. “This is how water is operating in California under climate change. We need to be thinking about and preparing for drought every year.”

Ortega says we also need to better understand the value of wetlands — and not just for the benefits to birds and other wildlife. “These wetlands are really the kidneys of society,” he says. “They strip away harmful contaminants, provide flood control and slow down the flow of water to replenish groundwater.”

And that groundwater is the sole source of water for communities in the Central Valley, many of which are disadvantaged.

“There’s definitely an environmental justice element to all this,” he says. “We have to be mindful of water quality and all of the other benefits that wetlands provide.”

![]()