I work on sustainability and political reform in Washington, D.C., but I still call the Pacific Northwest “home.” That’s why I’m heartened by the critical mass of electoral reform initiatives on ballots throughout the region this fall.

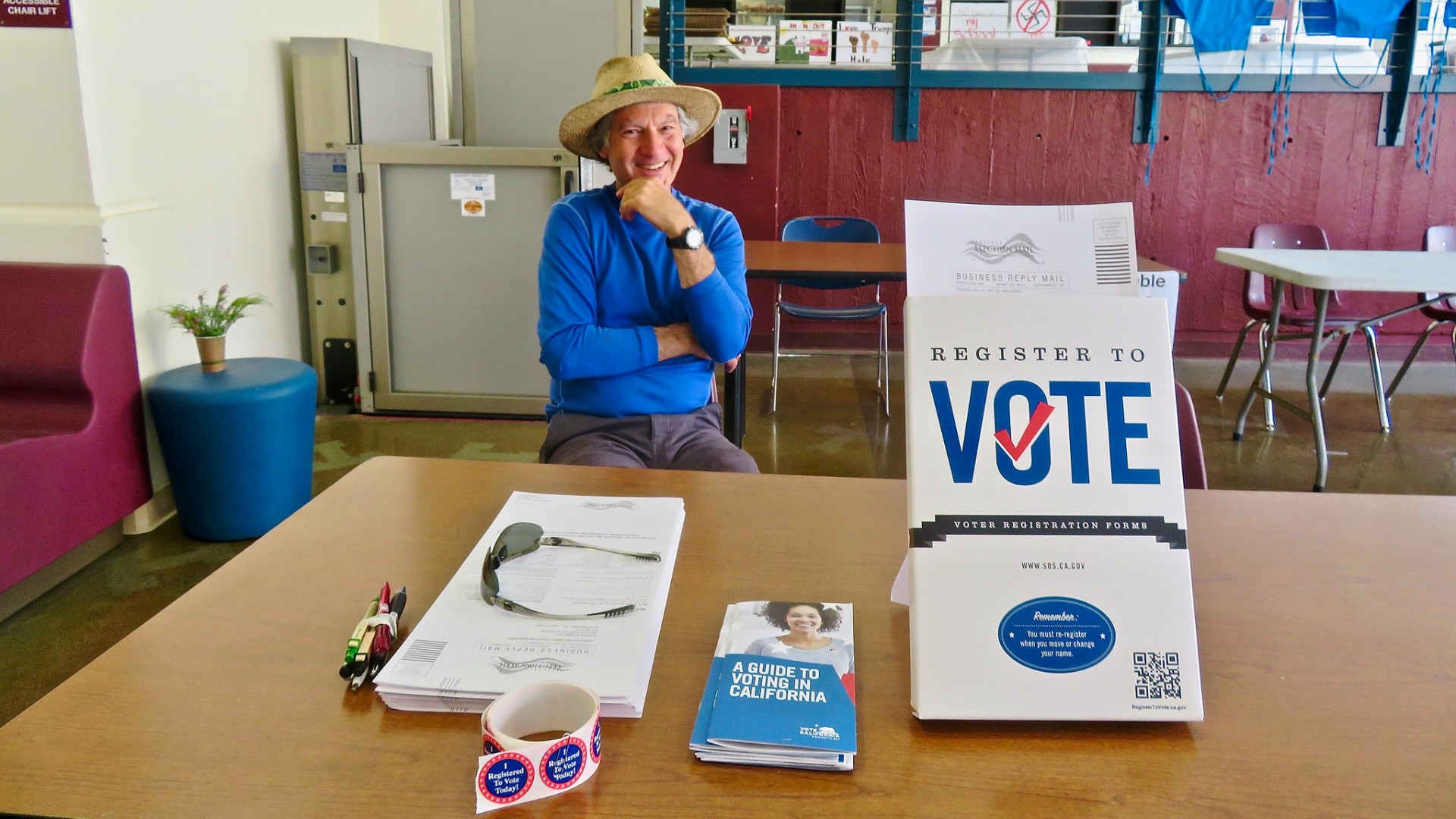

In Seattle, Initiative 134 would allow for a form of “approval voting” that empowers voters to choose more than one candidate per race in primary elections, preventing vote-splitting chaos in crowded primaries. Voters in Portland and various counties throughout the Pacific Northwest have opportunities to implement “ranked choice voting,” which asks voters to select their first choice, second choice, and so on down the line and determines the winner(s) through “instant runoffs.” Across the Cascadian hinterlands, Alaska conducted its first ranked choice election this August, and Nevadans will vote for statewide electoral reform in November.

It’s worth understanding how these reforms improve our elections — as well as our environment. They will allow voters to better express their true preferences when choosing elected officials and discourage political hacks from gaming the system. This generally leads to better policy outcomes.

In particular, ranked choice and approval voting help secure the policies necessary to build a sustainable future.

Larger Winning Coalitions

To understand how these reforms create better environmental outcomes, it helps to borrow some ideas from political science.

“Selectorate theory” helps explain political leaders’ strategic considerations for maintaining power. According to this theory, political leaders calculate the ratio of the “winning coalition” (the number of voters needed for a candidate to win) relative to the size of the “selectorate” (all eligible voters). When this ratio is small — for example, in autocracies — leaders retain loyalty by bribing members of their small coalition with private goods financed through government coffers. When this ratio is large and democratic, leaders earn voter loyalty through providing public goods that everyone enjoys.

Environmental goods are the classic example of a broadly appreciated public good. In a 2015 paper, political scientists Xun Cao and Hugh Ward measured the relative size of winning coalitions for thousands of elections worldwide against subsequent levels of air pollution. Their analysis showed that as a democracy experienced an increase in the size of the winning coalition, sulfur dioxide and other contributors to air pollution decreased.

By increasing the potential size of winning coalitions within a selectorate, electoral reforms contribute to a more sustainable future.

Now consider approval voting, where voters can choose multiple candidates. In our “choose-one” voting system, a winning coalition can be 50% + 1 of all voters. Every additional voter beyond this minimum threshold is expendable, so politicians are not motivated to earn their superfluous loyalty.

However, when an election uses approval voting, the size of the winning coalition equals the support of the second-place candidate plus one. For example, if 73% of voters are willing to “approve” of a popular challenger, then the incumbent needs 73% + 1 of voters to also “approve” of them to win the election.

In environmental terms, the best way to win the “approval” of a sufficiently large coalition is through protecting the many from pollution instead of allowing a few to enrich themselves through polluting.

By making candidates compete to be voters’ top-two or top-three pick, ranked choice voting similarly requires elected officials to pull together larger winning coalitions that prefer greener policies. When built on a preexisting foundation of voting rights and ballot access, both approval and ranked choice voting put fire under the feet of elected officials to do the right thing for the environment — or else risk being voted out.

Gateway to Proportional Representation

Ranked choice and approval voting make “proportional representation” feasible, such as the modernized system of government being voted on in Portland this fall. Unlike our dominant “winner-take-all” elections, winners from a proportional representation election reflect voter diversity.

Consider a hypothetical election to fill three seats, where multiple candidates from both major parties are running, and where 70% of voters prefer Republicans while only 30% prefer Democrats. In a ranked choice election for three-way representation, the threshold for winning is only 25%. Once the first-place winner — assumedly a Republican — is determined, the rankings of any voter required for that Republican to win first place are “locked” and any excess votes (in this case, more than the 25% threshold) are transferred to other candidates. The remaining votes are now 45% Republicans and 30% Democrats, meaning a Republican likely also wins the second seat.

However, the remaining votes for the final seat are 20% Republicans and 30% Democrats, assuring a Democrat will win. This result, where two Republicans and one Democrat represent an electorate that is 70% Republican and 30% Democrat, is a more balanced outcome than what would be expected from a “winner take all” election, where Republicans would win all three seats.

Proportional representation is a step toward environmental justice. Under our current “majoritarian” system of government, political minorities are excluded from representation, and in a racialized society like the United States they are too often synonymous with racial or ethnic minorities.

The only recourse for these groups to be systematically represented are as a byproduct of gerrymandering, where minority residents are “packed” into noncompetitive districts as a supermajority, or as an accident of vote-splitting, which can also backfire against minority candidates.

By contrast, proportional representation intentionally empowers minority voters with leverage to protest negative environmental conditions impacting their communities.

Because environmental concerns tend to be diffuse over widespread geographic areas, proportional representation also better secures general environmental outcomes. The larger multimember districts required for proportional representation are better scaled for evaluating the consequences of an environmental decision than smaller, single-member districts.

Political scientist Stephanie Rickard’s cross-national analysis of fishery subsidies gave this theory credence by showing how governments elected by proportional representation are more likely to pursue broadly appreciated environmental goods rather than serve centralized corporate interests.

(One caveat: Environmental interests do poorly under proportional representation if the voters are geographically concentrated as a strictly “urban elite” or “NIMBYs.”)

Better Stewardship of Resources

Electoral reforms are also good news for the planet for reasons that have nothing to do with politics.

By compressing multiple rounds of voting into one round, or two at most, electoral reforms reduce the environmental impact of an election while still securing the voters’ preferred candidate. This works because electoral reforms mitigate against vote-splitting, eliminating the need for runoffs to narrow the field of candidates or achieve a legally required threshold of votes.

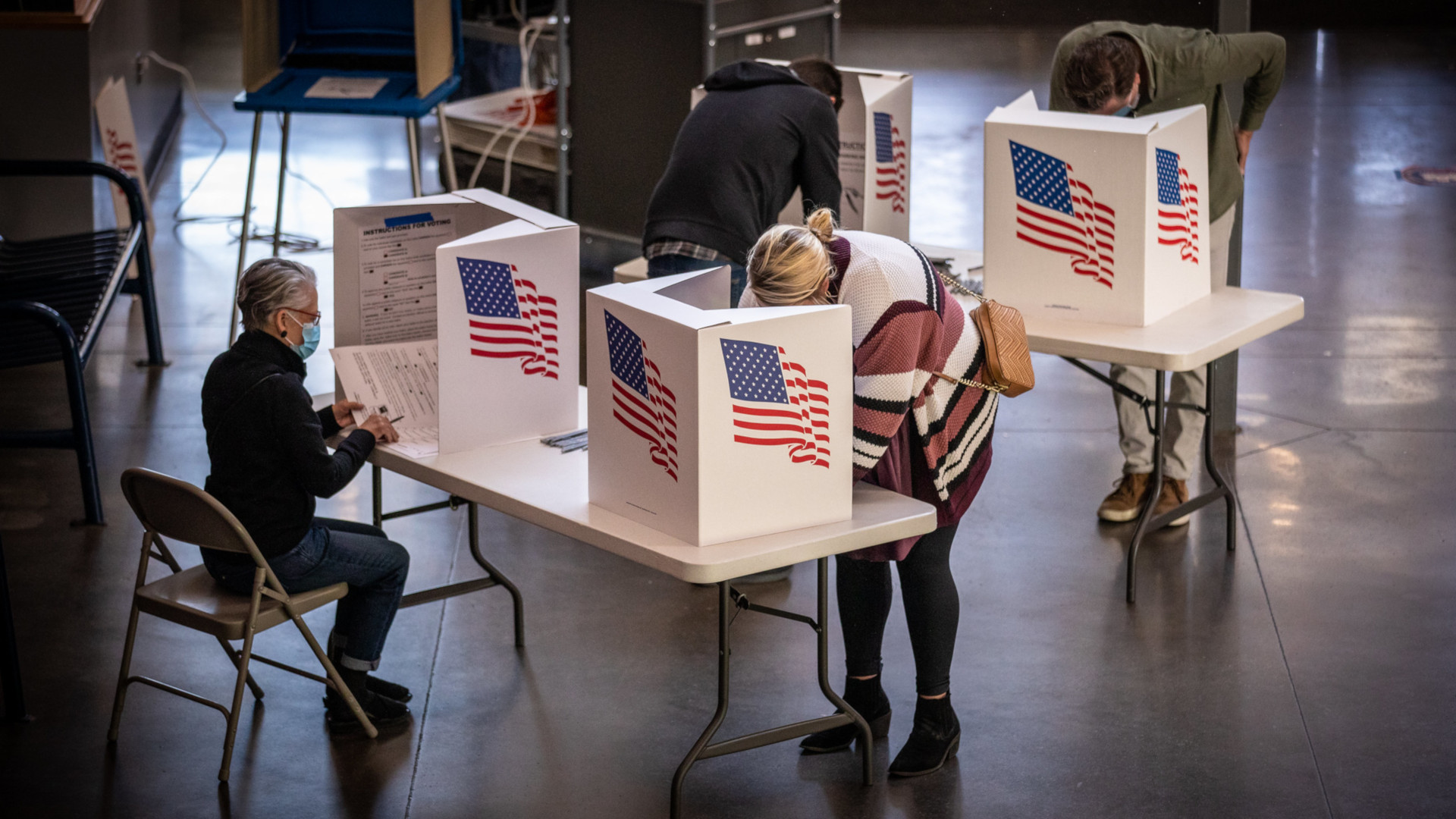

The environmental benefits are most significant when voting in-person. Every Election Day voters make an additional trip to their polling site, which often requires a fossil-fueled form of transportation, particularly in suburban and rural communities. For elections that yield hundreds of thousands of voters, citizens drive hundreds of thousands of extra miles.

Mail-in ballots leave less of a carbon footprint, but there’s a non-negligible environmental impact of printing paper ballots, envelopes, and other election literature for each voter. By reducing the number of election rounds, the environmental cost of electing government officials is reduced significantly.

The lesson is not that carbon-conscious voters should stay home. In fact, an analysis of the environmental outcomes of the 2019 Canadian federal election estimated that the median benefit of a pro-climate vote was equivalent to a 34.2 ton reduction in carbon dioxide, more than 14 times the reduction of choosing to live car-free for one year, and astronomically more than skipping a single trip to the polling place.

Neither does this imply a need to do away with paper ballots — having a paper trail is a crucial defense against the rising authoritarianism that casts doubt on the legitimacy of our elections. Rather, the lesson is a simple one: Ranked choice and approval voting are environmentally friendly because they eliminate unnecessary rounds of voting, in turn saving resources.

This matters because elections are among our most fundamental civic rituals. When we consciously decide our collective values through ballot measures and who we choose to send to elected office, we are also subconsciously internalizing other values about what we deem acceptable as a society.

From a strict emissions-accounting perspective, the environmental impact of a single election is only a drop in the bucket compared to the thousands of other collective activities that occur daily. But what message does it send if we shun a simple reform that drastically reduces election emissions and waste? Through eliminating unnecessary voting rounds, we uphold sustainability as a civic virtue while fulfilling our democratic duty.

Thinking Ecologically about Elections

None of the reasons above are partisan. I did not suggest that we should game the system to elect more Democrats. That would go against the spirit of electoral reform. My advocacy for electoral reform has roots in my work building bipartisan pro-climate coalitions, where pro-climate candidates were routinely punished at the ballot box for their courage, and others became complacent without any competition on climate.

To stop this vicious cycle, we must reform our elections to reward courage, increase competition both within and between our two major political parties, and give third parties and independent candidates a fair shot in the process.

Rather than thinking in terms of “which party benefits,” it’s better to evaluate electoral reforms in terms of feedback loops and information flows. Feedback loops are the building blocks that create ecological systems — where a change in X leads to a change in Y, which in turn has either a multiplying or moderating effect back on X.

As we humans change our environment, we need a steady flow of information to make sure positive or “multiplying” feedback loops are not spiraling out of control and detect any weakening of negative or “moderating” feedback loops necessary for ecological stability. Because voting is a powerful way for individuals to make known their displeasure with how their local environment is being treated, election results themselves are a form of information flow, and voting bad candidates out of office can be a corrective feedback loop.

The voting methods we use during elections should acknowledge (rather than obfuscate) this ecological imperative.

Of course, electoral reform alone is not enough to save the planet. There’s a lag time, sometimes years or even decades, between when environmental degradation occurs and when humans become conscious of the impact on their lives. This gap is where movements for sustainability generally, and the climate movement specifically, draw attention to the imminent catastrophes awaiting us if we do not change our ways within the next few election cycles. Without these movements, electoral reform would only have a mildly positive effect on average and occasionally even a counterproductive effect.

But without these reforms, advocates within these crucial movements will grow frustrated and disenchanted with a political process that continues to fall short when addressing our ecological crisis.

For the sake of these movements, our planet, and democracy, I hope voters across the Pacific Northwest and beyond will choose to embrace a politics that has been reimagined for a more sustainable and just future.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Previously in The Revelator:

Voter Suppression Is the New Climate Denial