When I was a child, my mother instructed me to stop playing outside and come home at the sight of the first twilight firefly. For many years I believed what most children believe: that when darkness falls, the day’s fun is over. It wasn’t until my stint as a Student Conservation Association intern at Arches National Park, many moons ago, that I began to explore the night sky and all the secrets it holds.

Dr. Wan Faridah Akmal Jusoh had a similar experience. As the Malaysian conservation scientist recounted in a talk at TED Women in Atlanta, Georgia, last fall, she and her siblings grew up in a “superstitious, conservative community” and were always told to return home at sunset. “This particular rule made the night seem mysterious to me,” she recounted at the conference, where we first met. “I spent my school years admiring the dark, but never got around to really exploring it.”

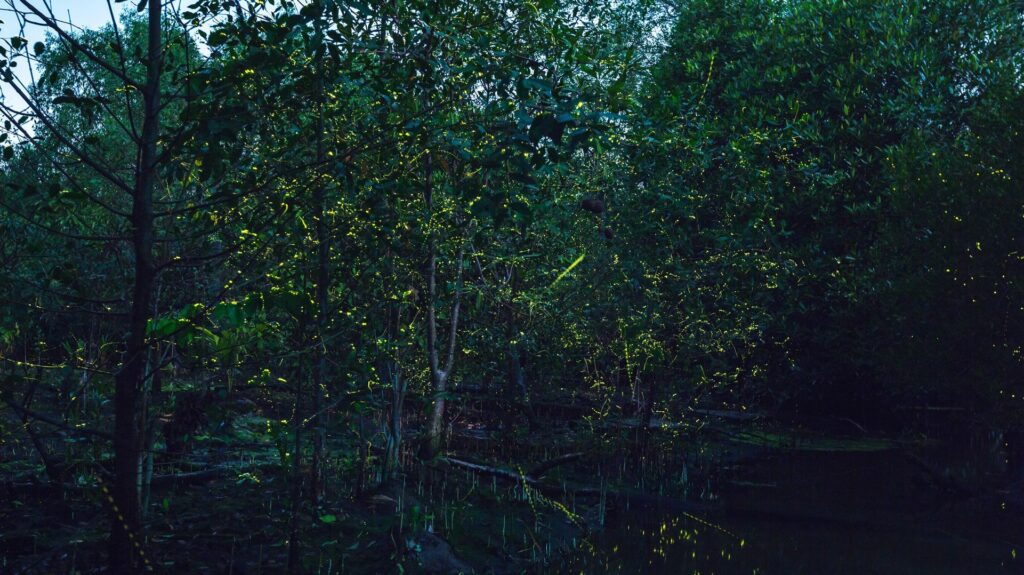

When she was a young scientist, that began to change. On a late-night boat ride through a mangrove estuary one evening, she found herself surrounded by thousands of fireflies, all blinking in unison. As she said in her TED talk, “That is the moment I will never forget — the moment I officially fell in love with kelip-kelip,” the local name for fireflies.

Now a senior lecturer in biodiversity and conservation at Monash University in Malaysia, Jusoh has dedicated her career to firefly research and conservation. Among her accomplishments, she recently coauthored a paper outlining firefly threats and conservation strategies around the world.

Another area of Jusoh’s research focuses on the genus Pteroptyx, also known as congregating fireflies. Like the insects she saw that fateful night, Pteroptyx gather in large swarms in trees and shrubs along tidal rivers in mangrove swamps and flash their lights in nearly perfect synchronicity. Because of these displays, the IUCN refers to them as “icon species.”

But even these icons are in trouble. Last month, just a few days before World Firefly Day on July 6, the IUCN Firefly Specialist Group announced that four congregating species — the Comtesse’s firefly (Pteroptyx bearni), synchronous bent-wing firefly (P. malaccae), perfect synchronous flashing firefly (P. tener), and nonsynchronous bent-winged firefly (P. valida) — have been assessed as vulnerable to extinction, one step above endangered. (The extinction risk of the majority of firefly species has yet to be assessed, something the Specialist Group is working to address.)

On the day of the IUCN Red List announcement, Jusoh and I reconnected over video to discuss her work.

There are more than 2,200 known species of firefly. They’re found on every continent except for Antarctica. And each type serves as an indicator of its habitat. Why is this important?

Fireflies are so important. I think the first thing that we talk about is balancing the ecosystem. There are also other insects that play a role like that, but if you look at fireflies, their life stage has [a] different role.

When we talk about firefly larvae, we are also talking about maintaining good habitat for their prey. So, for example, we’re talking about firefly larvae eating snails. The snails require good water quality. When you don’t have good water quality, the snail population will decrease and the fireflies’ population will also decrease.

But I also like to talk about specific fireflies — for example, the aquatic firefly. We don’t have many, at least not all over the world, but there are aquatic fireflies [who] can swim. They require high quality water to actually live in the water.

It’s not just about fireflies alone. When you remove the firefly from the ecosystem, you are disturbing the other parts of the food chain.

For those of us who are not scientists and have not devoted our lives to fireflies, what can we do to help foster healthy habitats so that the widest range of species of fireflies can thrive?

This might be funny, but as a collective group of firefly researchers we all say that the first, very simple thing that you can do is turn off the lights when you don’t use them.

That’s the easiest thing that we can do as citizens because fireflies are talking to each other using signals. And when you have the light too bright, you will see decreased number of fireflies because you disrupt their communication.

And number two, if we cannot contribute scientifically, we can always go for a citizen science program. There are national recording systems, or something like iNaturalist. People [like me] actually get the data. Sometimes [users] will ask, “hey, what is this species?” Then experts try to identify it. And that’s very, very helpful. We can see that [and say] “oh, I have never seen this firefly, maybe next time I should visit this place.”

I think awareness, education, is very important. And in terms of contribution, nowadays almost every country has a citizen science program.

Maybe we think that it’s quite slow. Maybe we don’t see the return on investment in this kind of work. But in the long term it creates guardians, the people who one day, when they know there are fireflies here, will become the eyes and ears for scientists to help protect them.

You’ve spoken of the moment that you first saw the kelip-kelip dancing, and how it was a moment of wonder and excitement. And that moment has led to your entire life’s work. What would you say to people who have maybe not experienced that wonder? Where would they start to find wonder in nature?

I think it’s really hard to answer this. I think it really depends on how much you’re willing to be open to curiosity, open to new experiences. If you’re into nature, or if you have a high curiosity, you’re probably easily attracted to that kind of mystery. The message can be really powerful. But I think fireflies have a strength here that even by looking at them, you always have that magical moment.

In your talk you spoke of how coming home at twilight meant the night was mysterious to you. And that’s something shared by children around the world. How would you recommend we foster wonder of the dark in children?

People talk about the safety issue, of children being out at night, and that makes sense. But then when you grow up — and it was always instilled since you were young that you cannot go out — it feels dangerous. For you to get out and explore, there’s always many layers of doubt. But there are always ways to do it.

Nowadays we have a lot of opportunities to go explore an area that has already been established — for example, an ecotourism area. If we are not sure yet — and especially if we have that fear about about night — you can go with your family, ask your friends to come. The more the merrier.

Watch Dr. Jusoh’s TED Women talk below: