The Place:

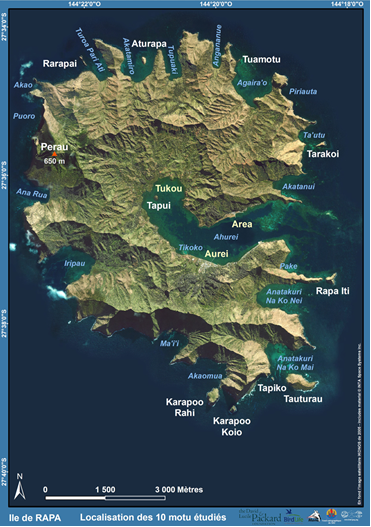

Rapa is the most southeastern island of the Austral Archipelago in French Polynesia. Ten islets, ranging in size from two to 64 acres, surround the main island, with a total land area of just 15.6 square miles (about 40 square kilometers). Rapa is sometimes called Rapa Iti, or “Little Rapa,” to distinguish it from Rapa Nui (better known as Easter Island). As of 2017 Rapa had a population of 507 people, a unique community that still follows old Polynesian traditions and speaks its own Polynesian language, Rapa. There are three main villages — Ahurei, Tukou and Area — all located around the central bay. It’s the only island in the country that has a winter season, usually between May and October, when the temperature can go down to 37 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius). That temperature difference is one reason there are seabirds and plants living here that don’t live in other parts of French Polynesia.

Rapa is the most southeastern island of the Austral Archipelago in French Polynesia. Ten islets, ranging in size from two to 64 acres, surround the main island, with a total land area of just 15.6 square miles (about 40 square kilometers). Rapa is sometimes called Rapa Iti, or “Little Rapa,” to distinguish it from Rapa Nui (better known as Easter Island). As of 2017 Rapa had a population of 507 people, a unique community that still follows old Polynesian traditions and speaks its own Polynesian language, Rapa. There are three main villages — Ahurei, Tukou and Area — all located around the central bay. It’s the only island in the country that has a winter season, usually between May and October, when the temperature can go down to 37 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius). That temperature difference is one reason there are seabirds and plants living here that don’t live in other parts of French Polynesia.

Why it matters:

Rapa is a place of extraordinary biodiversity, with at least 300 endemic species. The main inhabited island has one terrestrial endemic bird species, the endangered Rapa fruit-dove (Ptilinopus huttoni, local name Koko), which is the country’s largest fruit-dove.

Rapa Island is also a very important site for seabirds, with 11 species, mainly rare petrels, shearwaters and storm-petrels. Three species breeding on its uninhabited islets are now in danger of extinction: the Rapa’s shearwater (Puffinus myrtae or more locally as Kakikaki), white-bellied storm-petrel (Fregetta grallaria titan) and Polynesian storm-petrel (Nesofregetta fuliginosa) — the latter two locally named Koru’e. These species are very rare, difficult to observe, and of significant scientific interest. It’s suspected that the Rapa’s shearwater and white-bellied storm-petrel are endemic to this island — an exception among seabirds, who normally have large reproductive areas and breed in many different countries.

Rapa Island also has a unique human community. It was first settled by Polynesians, most likely in the 13th century. Their dialect developed into what is today the Rapa language. It’s believed that the depletion of natural resources on the island resulted in warfare, and the inhabitants lived in up to 14 fortified settlements (pa or pare, a type of fort, similar to the Māori pā) on peaks and clifftops.

Contact with Europeans brought liquor and disease, and between 1824 and 1830 over three-quarters of the local population died. Peruvian slavers raided the island as well. When a handful of their victims were returned to the island, they brought smallpox, which caused an epidemic. In 1826 there were almost 2,000 inhabitants; forty years later, there were fewer than 120.

The independent island kingdom was declared a French protectorate in 1867 and formally annexed on March 6, 1881. Subsequently the local monarchy was abolished. But the Rapa Island community still follows the old traditional ways — even if it has a governing town hall and an elected mayor.

The land belongs to the community and their descendants, so it can’t be bought by any exterior landowners. There is an elder council (Tohitu) that decides who the land goes to; if the land isn’t used for more than two years it can be taken away and redistributed to another local that needs it. There is also a Tomite Rahi (leaders from different factions of the island — religious groups, fishermen, taro planters, school teachers, etc.) that decides on rahui delimitations (protected marine areas where people are not allowed to fish, to protect food resources in the long term). These groups are not recognized in France or French Polynesia governments, but on Rapa Island their decisions are law.

On the island almost every plant, bird and fish species has a unique local name. That’s part of why it’s so important to protect these species: If they were to be lost to extinction, Rapa’s local community would also lose a part of its cultural heritage, which was already close to disappearing in the 1800s.

The threat:

Due to its large number of uninhabited islets and remoteness, Rapa is an ideal site for the protection of endemic animals and plants. But they’re threatened by invasive species.

Non-native species were introduced to Polynesia by humans and have profoundly altered the ecosystems where they settled. Invasive plants, for example, can gradually occupy a space and squeeze out local species. Other species can cause significant habitat destruction: Goats consume native plants and cause significant erosion, while predatory species like rats and feral cats directly attack chicks and eggs.

Threats to Rapa’s flora and fauna have increased dramatically. Twenty years ago overgrazing and extensive degradation of the endemic forests was caused by the introduction of cattle, goats and horses. Now the invasion of strawberry guava (Psidium cattleyanum) and Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea) has worsened the situation. Introduced plants had already invaded 64% of the island in 2005, including most of the forested areas. A local environmental NGO, Raumatariki, has tried to reverse the situation since 2012 by installing a fence around important native forest areas to prevent further grazing by domestic stock and setting up a native plant nursery. Further measures are needed to avoid this ecological disaster.

All offshore sites are affected by invasive grass species, especially Comelina nudiflora and Melinis minutiflora. These can form dense patches, restricting the growth of native endemic plants, which can consequently affect the breeding success of seabirds since they provide less protection against the weather conditions and make it more difficult for burrowing seabirds to nest.

Of the nine islets first surveyed in 2017, three are invaded by Pacific rats — a major problem for seabirds nesting in burrows or on the ground, as they eat chicks and eggs. Unstopped this will eventually cause the birds to disappear. For example, the Rapa shearwater population (a burrow-nesting species) has collapsed from 1,000 pairs in the 1990s to fewer than 200 pairs today.

The restoration of the important indigenous forest areas on Rapa main island and offshore islets are essential projects for the Polynesian Ornithology Society, or SOP Manu, and its partner BirdLife International. The disappearance of the Koko and these seabird colonies would constitute a significant loss of the Polynesian cultural heritage and undoubtedly serious damage to our environment.

My place in this place:

I work for SOP Manu as an island restoration project manager, and my projects take place in multiple islands across French Polynesia. With the help of BirdLife International, I’m in charge of organizing restoration projects on uninhabited islets that are biodiverse or have populations of rare bird species. Rapa was of course identified as one of the hotspots, especially for seabird colonies. Since it’s very remote, there have not been that many visits from scientists — for birds especially. The last ornithological work was done in the 1990s.

The first time I went onto Rapa was during school holidays in 2017, when I joined one of the special ship rotations for children of the island to go home for two weeks every six weeks. There’s only one primary school on the island, so kids need to leave home when they’re 11 years old for schooling.

To go there, you really need to be prepared. A week before, you have to send all your gear and food onto a ship named the Tuhaa Pae, take a flight to an island the ship will stop at before going on to Rapa, and then spend 36 to 48 hours at sea.

With a team of scientists from SOP Manu and BirdLife International, we had to survey the fauna and flora on 10 different islets. It was a lot of work — during very bad weather. The town hall lent us a very old small boat. Sadly, while we were camping, we lost it! The rope broke during the night due to tumultuous waves and it floated away. We had to have a team of locals come pick us up in a bigger boat. The scariest part was jumping off the islet into the waves to catch the buoy and be pulled onto it. Of course, BirdLife helped us compensate the loss of the boat with a new one, so we could continue to have a good relationship with the town hall and the local community.

The second time I went, during school holidays in 2018, everyone remembered me: “You were with the group who lost the boat!” I met more locals than I had the time before, as my role was to start training them on biosecurity: We’d discovered on the previous trip that ship rats were absent from the island, and we wanted to keep it that way. Again, it was super fun, but bad weather limited what we could do.

I thought then that if I wanted to do more, I’d have to spend more time on this island. With the president of Raumatariki and my other colleagues from SOP Manu, we decided to form a team to do more work on the restoration project and applied for the Young Conservation Leadership Award.

I remember going for the third time in 2019, alone, to join Tiffany, Raumatariki’s president, and help her with the YCLA project for six weeks. At that time, I was in a slump because my SOP Manu projects on other sites weren’t working out. It had just been so discouraging to even be in this field. But the third trip saved me. I got to know more about Rapa and its local community, and it made me passionate about conservation again. Their involvement in our project and their views on nature are what I think of when I think of how our Polynesian society should be: protectors of our island resources for future generations and protectors of our cultural heritage.

I’ve returned three times since then. Each time I visit, people recognize me — they’ve kind of adopted me as their own bird expert. I’m often invited to village meetings and events. I get so much help from them, both in the field and when I’m staying in the village. They like to share everything, and if we walk around we never go home without a gift like fish, fruit or vegetables.

At each public meeting we organize to share our progress, a lot of people attend and give their opinions. In 2020, during my fifth time on the island with Raumatariki, we brought school kids onto islets to see birds and onto the main island restored forest sites to remove invasive plants. I learned a lot of their culture and we helped kids know more about their birds and plants.

I’m now very attached to this community and this beautiful island, and I really hope I can continue to help them restore the sites. Each time we arrive, we get flower crowns; each time we leave we receive necklaces of local blue seeds (which means you will come back). Life on Rapa isn’t perfect, and sometimes our visions clash with public opinions, but having the mayor, his employees and the tohitu (elder council) support our projects has made my experience a joy. I feel I’ve learned a lot more about the Polynesian way of life than during my lifetime in Tahiti, which has become modern and individualistic.

They probably won’t read this, but Tongia maitaki (thanks a lot!) to everyone on Rapa Island. You’re the best.

Who’s protecting it now:

Raumatariki protects the environment and cultural aspects related to the nature of the community. They produce indigenous plants in their plant nursery, remove invasive plant species, and plan to restore important archeological sites such as fishing pools (Paeka) and forts (Pa). They’re our local partners in protecting the birds of the island, so we train volunteers and staff to identify birds and invasive species, as well as in biosecurity and related subjects. In exchange they help us communicate with the population and give us logistical support.

What this place needs:

Funding is of course essential. Volunteers would be welcome, if they’re ready to spend months in remote conditions. But paying someone local to oversee these tasks full-time would be ideal.

We also need more scientific help in researching rare birds, their habits, and ways to protect them and restore their habitat. Some plant species, too, are so rare we just don’t know how to produce them on a larger scale for replanting at restored sites.

Lessons from the fight:

I’ve learned that the local community must be involved in conservation projects. Without their support, you can’t effectively protect these sites in the long term. Even though community dialogue can slow down the projects — since there are always diverging opinions — you learn to adapt your methods. Having everyone working together is better for the future of the island’s environment and for the future generations of these remote communities.

Previously in The Revelator:

Protect This Place: The Fragile and Enchanting Costa dos Corais

![]()