The Place:

An unprotected 740-plus-acre hardwood forest in southeast Tallahassee, Florida, called the English Property Planned Unit Development and PUD Amendment. This majestic upland hardwood forest, privately owned by the English family for a couple of generations, has withstood the test of time but has now become a figurative endangered species.

An unprotected 740-plus-acre hardwood forest in southeast Tallahassee, Florida, called the English Property Planned Unit Development and PUD Amendment. This majestic upland hardwood forest, privately owned by the English family for a couple of generations, has withstood the test of time but has now become a figurative endangered species.

Why it matters:

This forest abounds with wildlife. According to a Biodiversity Matrix Report recently obtained from the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, a federally threatened flora species called zigzag silkgrass has been documented in or near this forest. The same report found a likely or potential presence of federally threatened and endangered fauna species such as the eastern indigo snake, wood stork, gopher tortoise and red-cockaded woodpecker, along with myriad other native flora and fauna.

This unprotected forest has been part of a crucial natural wildlife corridor that extends south into the Apalachicola National Forest. Much of the urban green corridor that still connects to this English forest is already protected, thanks to a privately preserved, sustainable conservation easement and an adjacent neighborhood with a conservation park maintained by the city of Tallahassee. Construction on the English forest would sever this wildlife corridor and add barriers for species roaming through these habitats.

In addition to featuring amazing biodiversity, this forest sits on a prominent geomorphic feature called the Cody Scarp, formed from an ancient shoreline. The land’s elevation significantly drops at the Woodville Karst Plain, an area characterized by active features such as sinkholes, karst lakes, a spring head, springs and underground streams. According to the Basinwide Management Action Plan, prepared by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, this site is in the Wakulla Spring Basin, a recharge area for the Wakulla Springs. This forest’s karst plain is a high-priority protection area uniquely vulnerable to runoff and stormwater containing nitrogen. Contaminants could easily seep into the Floridan Aquifer, which is connected to the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park, and other sinkholes in the park located about 15 miles south of Tallahassee.

My place in this place:

As a youth, I spent many waking hours in a metropolis of sleek steel and glass, amid hordes of people, my day punctuated with pulsating sounds and lights. Yet at the end of the day’s sensory overload, an hour away by rail, a place of calm and silence always awaited me: this sylvan shelter in a valley nestled in small, forested mountains. Decades later, when driving by the English forest, I often reminisce about my childhood exploring those mountains, with city memories having long faded into hazy obscuration.

This city’s forests are also fading. Until the turn of the new millennium, lush greenery with majestic trees were ubiquitous at almost every corner of Tallahassee, our “Tree City.” Now our city is about to be engulfed by urban sprawl of short-lived, manmade constructions built without foresight or consideration of the environmental consequences.

The threat:

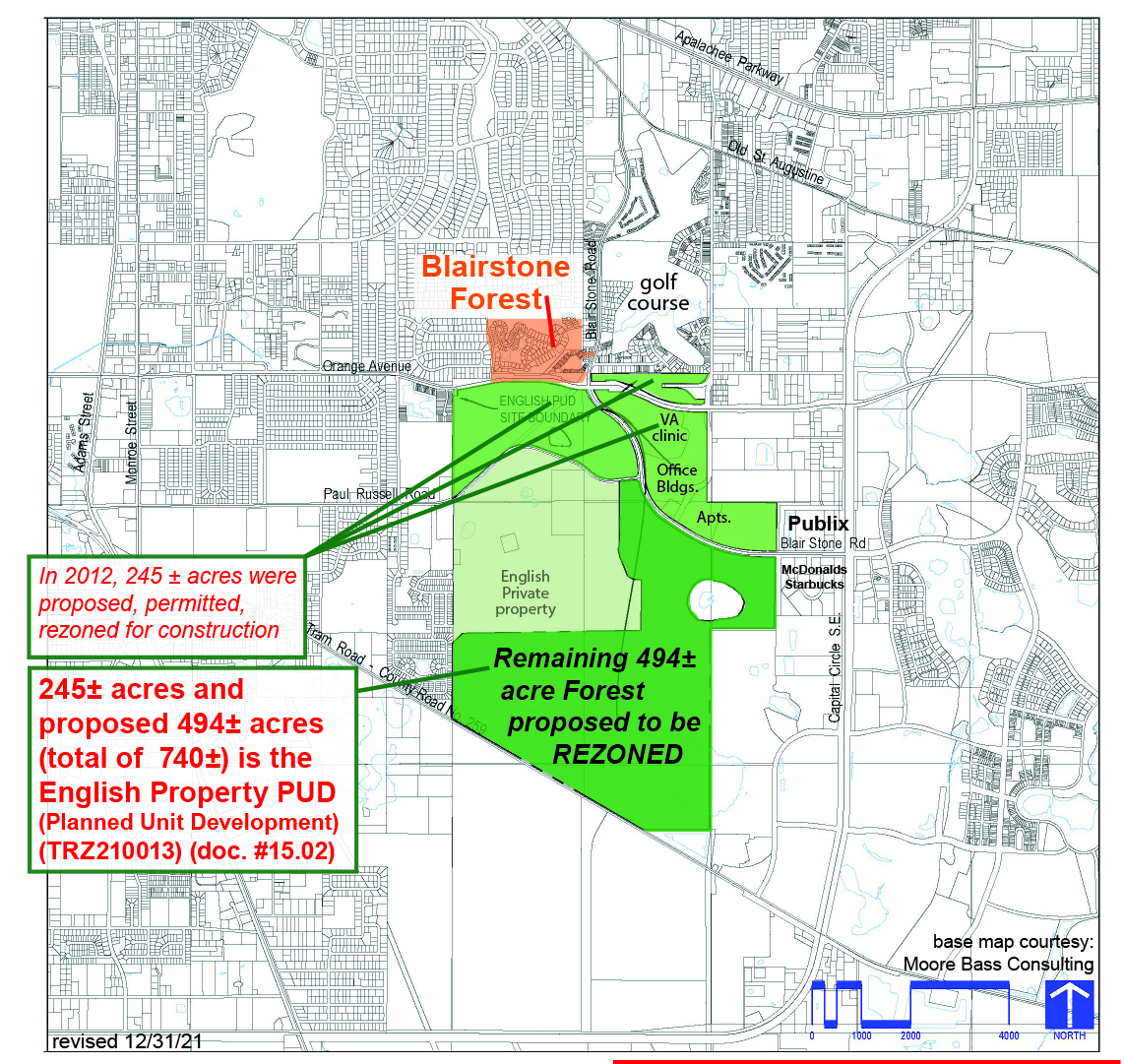

In 2012 the northernmost 245 acres of the English Property PUD were rezoned by the city of Tallahassee, and portions of the forest were completely clearcut. Construction soon began, resulting in the VA Tallahassee Outpatient Clinic in 2016, Lullwater multistory apartment complex in 2018, and Russell State of Florida Office Park (ironically housing the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) in 2019. Builders still have plans for a 192-unit multistory apartment complex on a sloped 17-acre tract of this portion of the former forest.

But that’s not all: In August 2021, developers submitted an amendment to the city to rezone the remaining 494 acres of the existing English Property PUD. This would allow the realtor, developers and potential buyers of the land to construct medium-density residentials (multistory apartment complexes, single-unit homes), mixed office/commercial complexes and “neighborhood village centers” (a euphemism for gas stations, convenience stores and fast-food places), leaving a mere fraction of the property as disjointed “open spaces” with no evidence of conservation easements.

But that’s not all: In August 2021, developers submitted an amendment to the city to rezone the remaining 494 acres of the existing English Property PUD. This would allow the realtor, developers and potential buyers of the land to construct medium-density residentials (multistory apartment complexes, single-unit homes), mixed office/commercial complexes and “neighborhood village centers” (a euphemism for gas stations, convenience stores and fast-food places), leaving a mere fraction of the property as disjointed “open spaces” with no evidence of conservation easements.

If we don’t keep a watchful eye on the remaining 494-acre wilderness, it will be clearcut and broken up piecemeal into development parcels — an irreversible environmental disaster that would harm our communities. The area will see massive displacements and local extinctions of wildlife, including endangered and threatened species that have inhabited one of the last remaining intact ecosystems in the southeast area of the city.

Residents have fought similar proposed land-use plans for years, although pleas for preservation have mostly gone ignored.

Earlier this year, the developer abruptly revised the amendment, as a temporary measure, to only rezone 36 acres of the original PUD to expedite yet another multistory, 300-unit apartment complex. The realtor has made clear that they are still eventually going to proceed to have the remaining 494 acres rezoned — as a whole or piecemeal, as parcels — for construction, so this is not progress, merely a change in tactics.

The City Commission is scheduled to render a vote on March 23, 2022. If it’s successful, this would move the 36 acres into the 2012 PUD and rezone this parcel for construction.

Who’s protecting it now:

Regrettably, the forested English Property PUD is privately owned. Ironically, residents who live near this property appear to care more about the forest’s wellbeing than the owners.

In February, six individuals of different age groups and social standings presented during the City Commission’s public hearing. Their underlying appeals were to urge the city commissioners, as well as staff and the developers, to listen to them and to consider their concerns and suggestions. Shortly after the hearing, we finally coined our collective efforts Save the English Forest, or Save TEF. Having a united front will allow us to strive forward; we plan to meet with city staff, the developer and the realtor and propose modifications on the PUD. We also intend to request opportunities to meet with the city commissioners and the English family.

Meanwhile, the developer and the realtor who have been representing the English family have stated that the owners wish to do what’s best for Tallahassee, and they would like to “leave a lasting legacy.”

Ultimately, we’d like the real lasting legacy of this land to be preserved — along with its wildlife, its natural resources and its features. Allowing the forest to continue to thrive under public protection and conservation would be great investment that would endure for generations. We are currently collecting information on the how to have the remaining forest so it can be preserved by a local conservancy, the state, or a couple of other public entities. However, we know the final decision is up the owner of this forest.

What this place needs:

The bottom line is that the city of Tallahassee has become lax in permitting and rezoning constructions.

Prior to construction, it’s imperative that the city, the realtors, the developers and even the owner grant requested meetings with concerned members of the community whose homes neighbor the property and will be adversely affected. This will allow us to reexamine and modify the cookie-cutter land-use plan to significantly integrate more acres as conservation easements that will be connected so they can effectively function as permanent green corridors and sustainable wildlife habitats. Currently slivers of sloped, unbuildable and swampy, undesirable areas have been set aside as a “open spaces,” implying as conservation easements.

Since the southeast region of Tallahassee is currently deprived of a public-protected preservation area, designating a significant portion of the English property — specifically, areas that are considered vulnerable, buffering surrounding parcels and green corridors — could be acquisitioned by a national nonprofit organization and eventually handed over to the state of Florida or the Northwest Water Management District. For example, the 1,000-foot parcels adjacent to the city’s 52-acre Jack L. McLean Park could be publicly preserved and managed to promote passive nature-appreciation activities and to function as habitat for wildlife.

Lessons from the fight:

Since the initiation of raising residents’ awareness about the plight of the English forest, the first question I often encounter has been, “Can you win this fight?” All too often, it has become keenly obvious that most people only want to know the result, even before it happens. As with any undertaking, it is all in the laborious process. It has been one individual, one step, one voice, one flyer, one email, one small gathering, one commitment, one action at a time. There are no quick or easy shortcuts.

Not everyone supports our efforts — in fact, many have already made up their minds against them, believing there is nothing to gain from them. There have been oppositions to our efforts. Nonetheless, since time is of the essence, we strive to focus on the immediate task, with the responsive support and dedication of those who really care.

It is crucial to publicly address one’s concerns, make comments, and submit input on the record. Casual complaints, silence, complacency and inaction will yield nothing. One learns to become flexible in order to quickly react and adjust to sudden alternations and to last-minute meeting notifications.

It is a time-consuming, exhaustive endeavor. Yet, collectively, there is a chance to make a difference and to modify the course to save and to preserve much of the forest. We need to speak up for the forest and its wildlife — for they alone have no voice, no choice.

Follow the fight:

![]()

Previously in The Revelator:

Protect This Place: The Fragile and Enchanting Costa dos Corais