The Place:

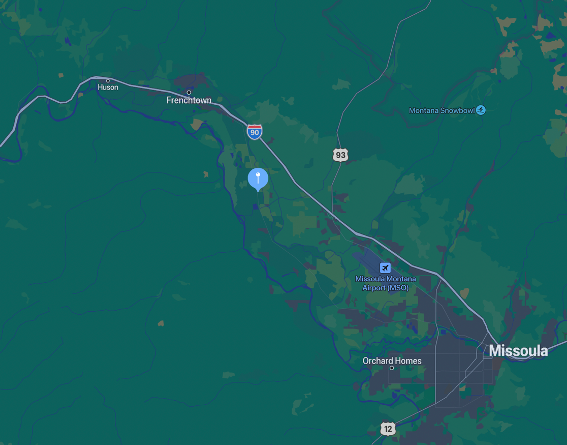

The Smurfit-Stone pulp mill site along the Clark Fork River in Montana was shuttered in 2010 but still poses an environmental threat.

Why it matters:

The Clark Fork River — situated in western Montana in the heart of the ancestral homelands of the Salish, Kalispel, and Ksanka peoples — is an important part of the history of the region, as well as the present and future for all who live here.

Rising out of the Continental Divide and flowing through a 14-million-acre basin, the river is a rich habitat for bountiful fish and wildlife, a magnet for recreation, an economic driver for our riverside communities, and an agricultural resource.

The threat:

The pulp and paper mill operated near Frenchtown — 11 miles from Missoula — for 53 years, discarding industrial and toxic wastes in unlined dumps, sludge ponds, and wastewater settling ponds next to the river. The huge dumps cover roughly 140–190 acres.

The wastewater ponds were drained long ago, but the soil and groundwater remain polluted with dangerous toxins, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, furans and arsenic. The fish in this reach of the Clark Fork and downstream suffer from contamination. The only thing separating the site from the river is a deteriorating, four-mile-long gravel berm. A major flood could breach the berm and cause an even bigger catastrophe by sweeping pollutants downstream for hundreds of miles

The wastewater ponds were drained long ago, but the soil and groundwater remain polluted with dangerous toxins, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins, furans and arsenic. The fish in this reach of the Clark Fork and downstream suffer from contamination. The only thing separating the site from the river is a deteriorating, four-mile-long gravel berm. A major flood could breach the berm and cause an even bigger catastrophe by sweeping pollutants downstream for hundreds of miles

My place in this place:

The Clark Fork River is the heart of our community and one of the central reasons people have lived in this place for millennia. It’s a gorgeous and dynamic river through every season, home to eagles, herons, moose, bull trout and beaver, among a myriad of other species.

Although the river is often characterized as the hardworking backbone of the industrial, agricultural and recreational economy, it’s also a place that inspires love and gratitude beyond its value as a resource. It has been described to me as a living relative who deserves respect and appreciation.

In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, author Robin Wall Kimmerer says, “In a consumer society, contentment is a radical proposition. Recognizing abundance rather than scarcity undermines an economy that thrives by creating unmet desires. Gratitude cultivates an ethic of fullness…” Protecting and restoring the Clark Fork River starts with a sense of gratitude and responsibility.

Last summer, while getting ready to launch rafts on a tributary of the Clark Fork for a four-day camping trip, I learned the Ojibwe word for “thank you.” Miigwech, we said to the river before stepping onto our small rafts and entrusting ourselves to the power of the high, fast waters.

“Miigwech,” I murmured this winter as I crunched across snow and stepped into the icy waters of the Clark Fork with the Missoula Cold Soakers — a group of over a dozen people who happily plunge into the cold river every Saturday. As I slowly stepped deeper and deeper in the cold water, I was thankful for this place of such immense beauty, which brings our community together and reminds us of the joy of being alive.

The Clark Fork River is the place I take visiting friends and relatives when I want to show off our home. It’s the place I take my child for an afternoon of play. I walk along the riverbanks when I need to think or simply move my body in fresh air. Through it all, I recognize that we owe the river a duty of care, not only for all it gives us, but also for its place in the ecosystem and the generations that will follow us.

Who’s protecting it now:

The Clark Fork Coalition was started as a nonprofit in 1985 by a group of concerned locals who worked together to keep the pulp mill from discharging waste directly into the river, year-round. Since then, the Coalition has grown, expanding advocacy and restoration work throughout the Clark Fork River basin. But it’s still focused on the mess at the now-closed pulp mill.

In 2011 the Environmental Protection Agency started an investigation of the site and determined that International Paper, WestRock and Wakefield are the corporations responsible for cleanup. But over a decade later, cleanup has yet to begin.

In April American Rivers named the Clark Fork River as one of America’s 10 Most Endangered Rivers due to the remaining toxic contamination and the threat of a flood causing an even bigger environmental catastrophe.

What this place needs:

To protect this place, we need more robust data about the extent and location of contamination. Then we need the EPA to act quickly to clean up the dumps, remove the berms and restore the floodplain.

Lessons from the fight:

Protecting a place as large and varied as the Clark Fork Watershed requires perseverance, resources and passion.

We have learned that a vital factor in protecting the river is community engagement. When people understand how the ecosystem works and how we can live as part of it, they are willing to fight for solutions that support human needs while protecting the river now and in the future.

All the work we have accomplished in the basin — stopping the original discharge permit from the mill, restoring flow levels and fish passage in tributaries, tracking the progress on another Superfund site upriver — have come about because concerned people learned about the challenges, understood the value of the river and acted out of love for this place.

The Clark Fork Coalition and its partners have launched a Clean Smurfit Now! campaign to educate the public and decision makers about the threat and put pressure on the EPA to take action before a major flood makes the situation worse.

Follow the fight:

The Clark Fork Coalition, American Rivers and Montana Public Interest Research Group are collecting signatures and comments to send to the EPA expressing concerns and pushing action.

Watch these videos on the damage Smurfit-Stone causes on the Clark Fork River to learn more.

![]()

Previously in The Revelator:

‘There’s No Memory of the Joy.’ Why 40 Years of Superfund Work Hasn’t Saved Tar Creek