It’s not always easy to separate the man from the myth.

Take Johnny Appleseed, for example. To most people Johnny’s a figure of fable, a loner who wandered the country with a tin pot on his head, dropping apple seeds into the soil wherever he traveled, spreading the fabulous fruit from American coast to coast.

Pretty much all of that is false.

The truth of Johnny Appleseed — a complex man named John Chapman (1774-1845) — is much more interesting. Chapman was a businessman, a nonstop traveler, a missionary, an avowed pacifist and socialist, a pioneering advocate of protecting nature, an anti-industrialist and yes, a man who loved his apples.

Alas, the historical truth about this man-become-myth is also more than a bit more frustrating for people who want to dive into the details. Many details about Chapman’s life remain a mystery. He left few records, and precious little was written about him while he was still alive, making it difficult for modern writers to reconstruct his coming and goings nearly two centuries after his death.

So what’s a biographer to do with this dearth of information? One answer is to write about what little we do know, while also delving into Chapman’s significance, both in his own time and today.

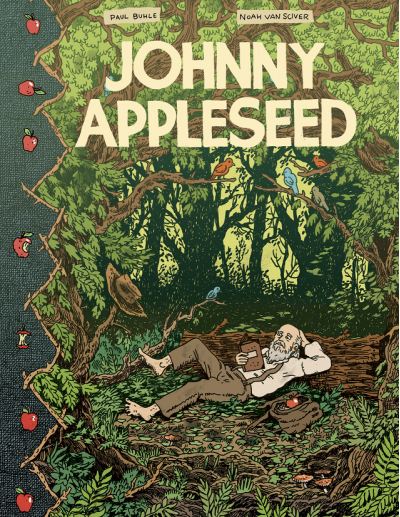

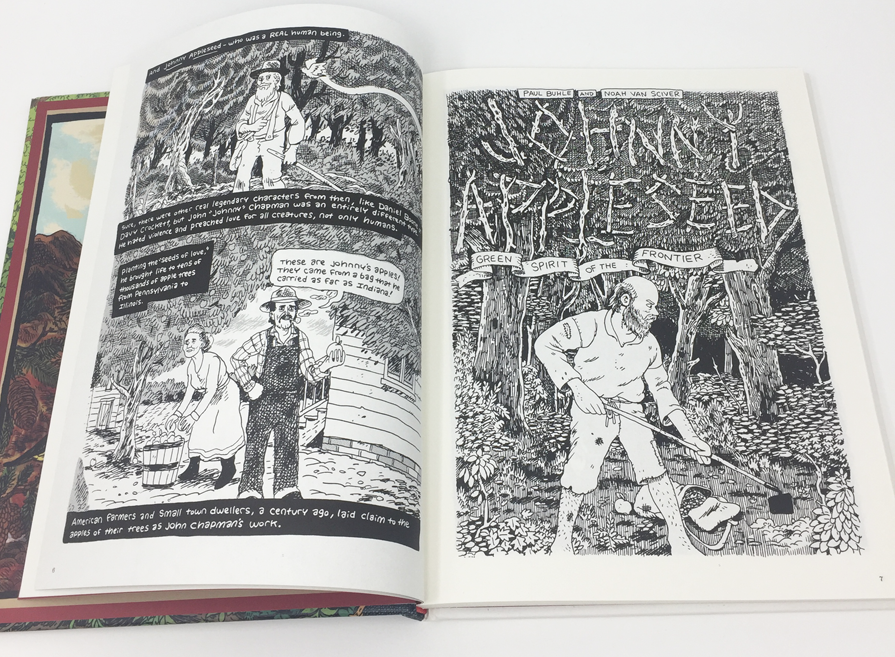

That’s the path taken by scholar Paul Buhle and cartoonist Noah Van Sciver in their new graphic novel, “Johnny Appleseed” (Fantagraphics Books, $19.99). The book covers the few facts that we know about Chapman’s life and simultaneously explores the Appleseed myth, along with the nascent philosophies and religious trends of his day.

That’s the path taken by scholar Paul Buhle and cartoonist Noah Van Sciver in their new graphic novel, “Johnny Appleseed” (Fantagraphics Books, $19.99). The book covers the few facts that we know about Chapman’s life and simultaneously explores the Appleseed myth, along with the nascent philosophies and religious trends of his day.

And what a day (or century) it was. Chapman was born just before the American Revolution and died not long before the Civil War. These were heady, contradictory years for American society. As Buhle writes in his introduction, Chapman’s wandering decades were a time of “ardent reformism including women’s rights, abolitionism, and vegetarianism,” all of which existed side by side with “slavery, the advancing white settlements, the plundering of natural resources, and the dispossession of Native Americans.”

Interestingly enough, Chapman’s story starts with both apples and the absence of American Indians. In one of the book’s early scenes, Buhl and Van Sciver recount a discussion between young Johnny and his widower father, Nathaniel, a veteran of the American Revolution and the battle at Bunker Hill. The father reveals that the apple trees surrounding their family farm were planted by Iroquois before British soldiers wiped out both the people and their orchards.

We don’t know exactly how growing up with a veteran father in a landscape scarred by war affected young Johnny, but the through-line is clear: He grew up to become a planter of apples as well as one of the few American travelers who treated the native people he encountered with respect — enough so that they embraced him in return.

Chapman’s journeys started not long after his childhood ended. According to accounts, he grew weary of running a farm with his father and stepmother. One day in 1796, he decided, on the spur of the moment, to take off and start wandering, his younger brother at least briefly in tow. In depicting the departure, Buhle and Van Sciver illustrate both young Chapman’s appreciation of nature and the rapid loss of wildlife in the face of encroaching civilization. “To me,” Chapman says in the book, “Nature is God’s haven. I can tell you name of dozens of flowers, and trees of kinds we don’t have much anymore in our parents’ part of Massachusetts.”

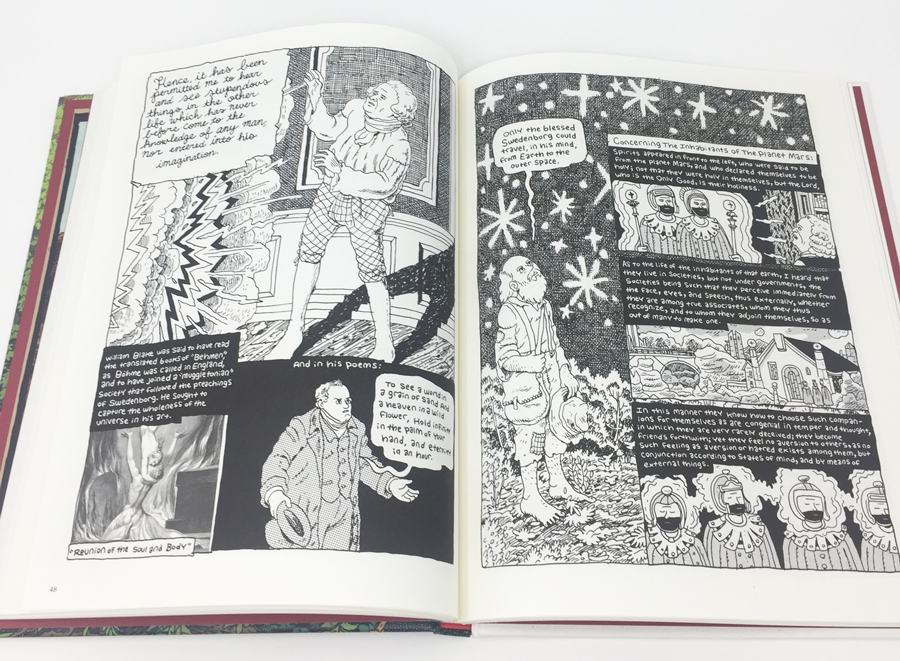

John’s brother didn’t stay on the trail long, apparently, so Chapman turned to a different companion: books. As he traveled he devoured volumes on religion and philosophy, an important element of the rest of his life. His journeys took place at a time of great religious experimentation in the Americas, seeing the birth of the Quakers, the Shakers and the Swedenborgians (today known as the New Church). This latter religion, with its embrace of nature and socialism, appealed to Chapman, and he became a missionary, spreading its word along with his apple seeds. Historians still debate exactly how Chapman encountered Swedenborgian teachings, but Buhle spends a full chapter exploring them in the book, providing context for how they influenced Chapman and, to a degree, modern environmentalism.

No matter what role religion played in his life, nature played a larger one. The scenes depicted in the graphic novel — lushly illustrated in Van Sciver’s delicate pen-and-ink style — show a country where Chapman felt at home, strikingly unfamiliar to our modern world. “In the few accounts of travelers meeting Johnny along his travels,” Buhle writes, “he expressed a simple delight of being alive in God’s kingdom of nature. And he might have asked, as a Midwest writer did about his childhood during Johnny’s old age, ‘Have you lain beside some pond, a broadening of a creek above an ancient beaver dam at night, and watched the muskrats at the frays and feeding? Have you stood sometimes, in the sheer delight of it, and drawn into distended lungs the air clarified by hundreds of miles of sweep over an inland sea?’”

No, most of us haven’t. These worlds gone by, captured in black and white ink, give the book a haunting quality. You can’t help but wonder, as you read, what parallel world we might be living in today if Johnny Appleseed and his ilk had not become such footnotes in history — if their thoughts and ideas had taken seed, like apples, across the American landscape.

Alas that world is long gone, but Johnny Appleseed’s influence — and that of the philosophies he embraced — still runs through a deep vein in modern life. Buhle weaves together a tapestry of linked threads, ranging from naturalist John Muir to the migrant workers of the early 20th century to Woodie Guthrie and the Beat poets and beyond.

And then there’s Chapman’s physical influence on our daily lives: the apples that pervade our agriculture, our stores and our diets. Even this is an environmental story: Buhle briefly recounts the 1980s fight against the apple pesticide Alar that in many ways still influences the environmental movement.

Yes, Johnny Appleseed as most of us know him may be a myth. The details of his real life are few and far between. But his influence remains, and this book illuminates that legacy.

Previously in The Revelator:

John James Audubon Takes Flight in New Graphic Novel