As 25 wildfires burn through California in another record-breaking fire season, it’s a good time to talk about the state’s forests and their future. That’s the focus of a new book — The Forests of California — from Oakland, California-based artist and naturalist Obi Kaufmann.

Wildfire is an intrinsic part of most landscapes in California, so much so that Kaufmann says, “trees themselves in California are fire waiting to burn.”

Kaufmann’s new book isn’t focused on wildfire specifically (that will come in a later volume), but he does lay important groundwork to help people better understand the complex ecology of the state’s varied forests and why they are so important.

“Although California accounts for only 3% of the land area in the United States, more than 30% of all plant and vertebrate species in the nation find habitat here,” he writes.

But this amazing biodiversity and the systems that link it together are under threat from human development, climate change, misguided management and invasive species.

Forests of California, the third book from Kaufmann, is no ordinary reading. It’s a “field atlas,” a construct of his own making and not to be confused with a field guide. This 600-page volume describes ecological forces at work in California’s forests with artistically rendered data, watercolor drawings and maps, detailed research, and knowledge accumulated from decades exploring the backcountry.

Kaufmann calls the book “an activist’s guide” and a “work of hope,” meant to inspire people to help protect California and other places they love.

We talked to Kaufmann about geographic literacy, overcoming “plant blindness” and his favorite forests.

Unless folks have picked up your first book, The California Field Atlas, they’re likely unfamiliar with this genre. Can you explain what it is?

The “field atlas” is a genre that I invented in order to tell the story that I wanted to tell.

I think most people confuse it with a field guide, which would be a reference book aimed towards biological identification — or looking at the what of things. But a field atlas is a story of the character of California that has always been, continues to be, and will always be despite our very successfully imposed urban veneer over the past 170 years.

I am not concerned so much with the what of things, or even the where of things, which is funny for something calling itself an atlas.

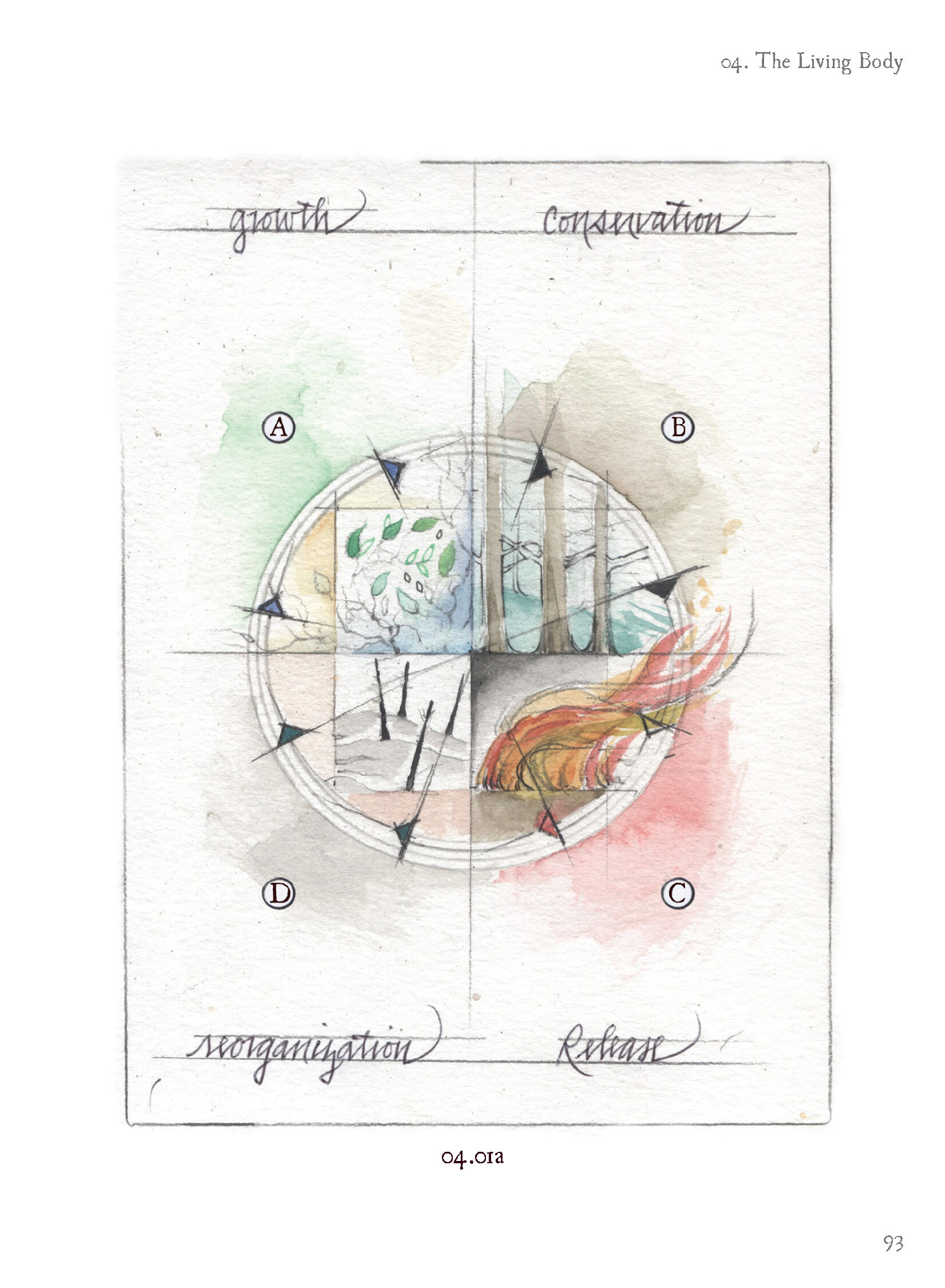

But I am obsessed with learning about the how of things. How the whole cycle works from growth through conservation to release, and then regrowth. Most often, and dramatically, this is expressed across California’s extremely varied topography through fire.

And I’m interested in how the resiliency mechanisms within those ecosystems are triggered and how succession works within the forests in California.

The book is a unique combination of research, art and science. How did you decide to organize it?

I’m fascinated by systems thinking. And I think ecology is an academic discipline that really lends itself to those kinds of models. The organization is basically structured around three concentric circles. The first inner circle, circle A, is tree associations. How tree species in California tend to grow in each other’s proximity. The very skeleton of what might eventually become habitat, which would be circle B.

How then, once these trees are grouped together in particular locales, do they attract other species? Maybe it’s an understory or what is happening along the forest floor. Maybe we can then include wildlife that finds its niche opportunities within this arboreal architecture.

And then finally the largest circle, circle C, would be the forests themselves. And that is where I use the contrivance of contemporary political boundaries across the 23 national forests as they are currently described in California, which covers roughly half the state’s total land area.

I go through and give six examples in each one of the national forests of what habitats and forest types exist within them.

That gets to my larger mission, which is to alleviate what has been called “plant blindness,” which is [when people fail to see the variety around them and just think] ‘a tree, is a tree, is a tree.’ In fact, here in California we enjoy an elite class of biodiversity that rivals all other portfolios of such measurement around the world.

We’ve got it all here in a unique, complex and very precious structure. And telling that story on a popular level where I am not only describing the trees themselves, but where the trees are, then that biogeography leads to a kind of geographic literacy.

I believe that our greatest tool as an informed citizenry is knowing what actually there is to protect. People protect what they love. And people love what they understand and know.

So we have to begin with an inventory of what there is to protect.

Do you have a favorite forest type or place in California?

I am really drawn to the area near Duck Lake in the Russian Wilderness, where 19 species of conifers live within one square mile. All of these conifer species together like that exist nowhere else in the world.

I’m also always looking for a way to get back to the High Sierra. The Crystal Range within Desolation Wilderness is not called that for nothing. When the sunset hits it on a clear July night, the whole place radiates a prismatic quality that will rival anything in the Italian Alps or anywhere else in the world for its alpine beauty.

And the third one I’m going to give you is my home mountain, Mount Diablo [near Oakland], which is such an excellent little topographic anomaly. It jets out like a thumb into the Central Valley and catches all the seeds from the Northwest temperate rainforest and all the seeds from the Southwest deserts to create this really unique little wildflower bloom every year.

It’s a jewel of biodiversity and wilderness just set like a diamond inside this hub of urban activity that is the East Bay.

For folks who don’t live in California and don’t have a rad field atlas for their home, how can they begin to better understand the place where they live?

I use California as my focus, but it really is a metaphor about looking at nature. You can swap out any of these maps with any other geographic region at scale — wherever you are in the world. This is the beauty of ecological science.

For me, it’s wrapped up in art and my own personal expression. But I think there’s a subtler truth here that these books are not necessarily about nature, but about me looking at nature. So on one level, these books are about me, which I think is a place to start for anybody.

I’d love to give license to whoever wants to make the field atlas of Minnesota. I’d love to see that. It can be done and it’s going to be your field atlas.

What do you hope for California’s forests and also for our environment more generally?

As we move through this century and begin our discussions about what 22nd century conservation policy might look like, we need to look at the shortcomings of 20th century policy and realize how much we’ve learned and how much indeed there is to learn.

What we’re actually learning now with the advent of such disciplines as corridor ecology and a better understanding of how wildlife actually move throughout a mosaiced habitat, is how to get more specific about the quality and diversity of habitat types that we should be conserving.

And we shouldn’t just talk about endangered species, but also habitat and perhaps even endangered phenomenon, like coastal fog. It’s a phenomenon upon which coastal redwoods, for example, depend. But it’s threatened by climate breakdown.

We have the opportunity to leave the 21st century with the natural world of California in better shape than we left it at the end of the 20th century, which is very a hopeful thing to say.

I’m often asked what people can do right now to help in response to all of the alarms going off — to help save this idea of nature in California or wherever else. And I always answer that question with a question: “When was the last time you went camping?”

And it’s hard to say under these apocalyptic [smoke-filled] skies right now, but I want to encourage anyone who’s feeling that to get out and take some time to literally take your shoes and socks off and put your toes into the cold, clear, clean water and feel nature around you.

Because it’s all still here. And breathe that deeply. Whatever happens next, we’re going to need you grounded, unpanicked and ready to change the story.

![]()