Never one to miss an opportunity, the Trump administration has repeatedly used the COVID-19 crisis as cover to enact unwise and dangerous environmental policies against the public interest and to forestall citizen input.

In recent days the Environmental Protection Agency has moved forward with weakening rules for automobile emissions and relaxing pollution standards. The Bureau of Land Management continues leasing for oil and gas drilling even as prices drop. And while much of the country remains under stay-at-home orders and faces the most disruptive public health crisis in a century, deadlines for public statements on forest plans have not been extended and formats for hearings about dams have frustrated citizens who wish to speak up for public resources.

Republicans are using today’s pandemic-related exigencies to undermine environmental protection and the public interest. We’ve seen it before. Hiding behind emergencies is from an old playbook.

Americans have heard excuses about national emergencies in the past and resisted them; we should again.

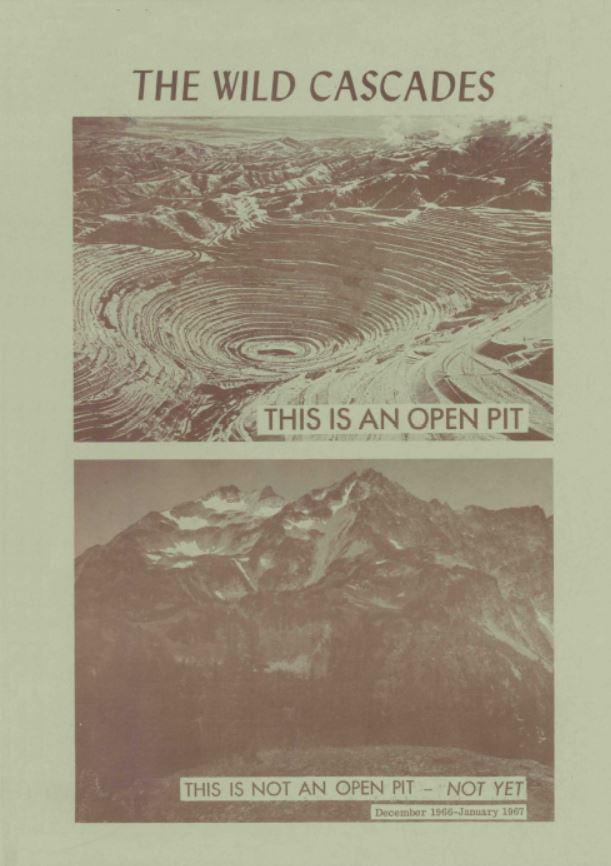

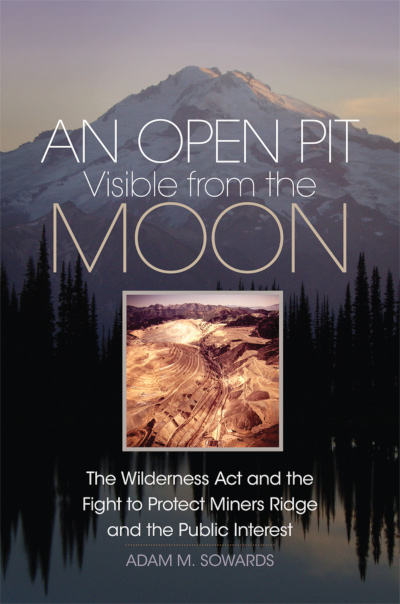

For a success story that resonates today, we need only look back to the era of the Vietnam War. In late 1966 Kennecott Copper Corporation announced its intent to develop a massive open-pit mine at Miners Ridge, within the Glacier Peak Wilderness Area of the North Cascades in Washington state. The mine would be near the iconic Image Lake, where backpackers enjoy perhaps the greatest views in the entire Cascade Range.

The context of the Vietnam War allowed Kennecott to argue it was merely fulfilling its duty to provide essential materials for the war effort, under which the General Services Administration had established a plan to stockpile critical materials for national security. Seeking to get new mines into operation, the agency promoted incentives that included loans and technical assistance.

Amid all of this, Kennecott pitched its proposed pit as patriotic.

Conservationists quickly grew alarmed. The Wilderness Act, which protected 9.1 million acres of federal land and established the Glacier Peak Wilderness, had just been signed into law in 1964. A compromise in the law allowed Kennecott and other companies to mine claims, but conservationists opposed the giant corporation and demonstrated the obvious: that open-pit mining and wilderness were incompatible.

Everyone knew the mountains held copper — the place name was Miners Ridge, after all. During World War II, at a time when minerals were similarly in demand, the War Production Board approved a road to the mine site, but it never was built.

This failure showed that maybe the copper in Miners Ridge really wasn’t that important after all. In 1967, as Kennecott pressed ahead, Polly Dyer, arguably the most important conservationist in Pacific Northwest history, reasoned in a public hearing that “If the Nation was able to pass through that desperate war effort without needing to utilize the copper in Miners Ridge, I am extremely skeptical about Kennecott’s assertion that it is necessary for today’s war operation.”

Dyer was right. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman, who had authority over the U.S. Forest Service, which administered the wilderness, soon admitted that the war effort and the public’s standard of living would “not suffer” one bit if the mine was “left undeveloped.”

For all its talk of selfless service to the nation, Kennecott operated primarily to bolster its bottom line — and to establish the precedent of mining within wilderness boundaries. The company’s president was exasperated by having to try the case in the press against an angry public. In his view, the company’s interest was the nation’s interest.

All of this is tiringly familiar in 2020, when the president’s personal interests, antipathy to the press and the public, and desire to establish untoward precedents animate virtually every utterance and policy.

What are the lessons we can take away from this?

Kennecott never built its mine, and the site remains secure as wilderness today, but that was not accidental. It took the efforts of citizens and organizations like the North Cascades Conservation Council and The Mountaineers publicizing the threat, writing representatives, and showing up at hearings. Through it all, Northwesterners demanded that the public’s interest be protected against the corporate bottom line.

In summer 1967 Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas traveled from his summer home in Goose Prairie, Washington, to attend a protest near the mine site. An aroused public, he said to 150 to 200 protestors on the trail, might “appeal to the community’s sense of justice” and declare there are values beyond “a few paltry dollars.”

The public interest, then and now, transcends the bottom line. It sustains democracy; it doesn’t suspend it.

We must not let our representatives use COVID-19 as an excuse to undermine environmental governance. We must continue to stand up for the protections that already exist, which protect not just our wilderness but human health.

History suggests that we can win these fights with determined resistance. Even amid the disruptions visiting our lives with lost lives and jobs, we need to keep one eye on the future and remember that our voices can make a difference.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()

1 thought on “No Sacrifices of the Public Interest in Times of Emergency”

Comments are closed.