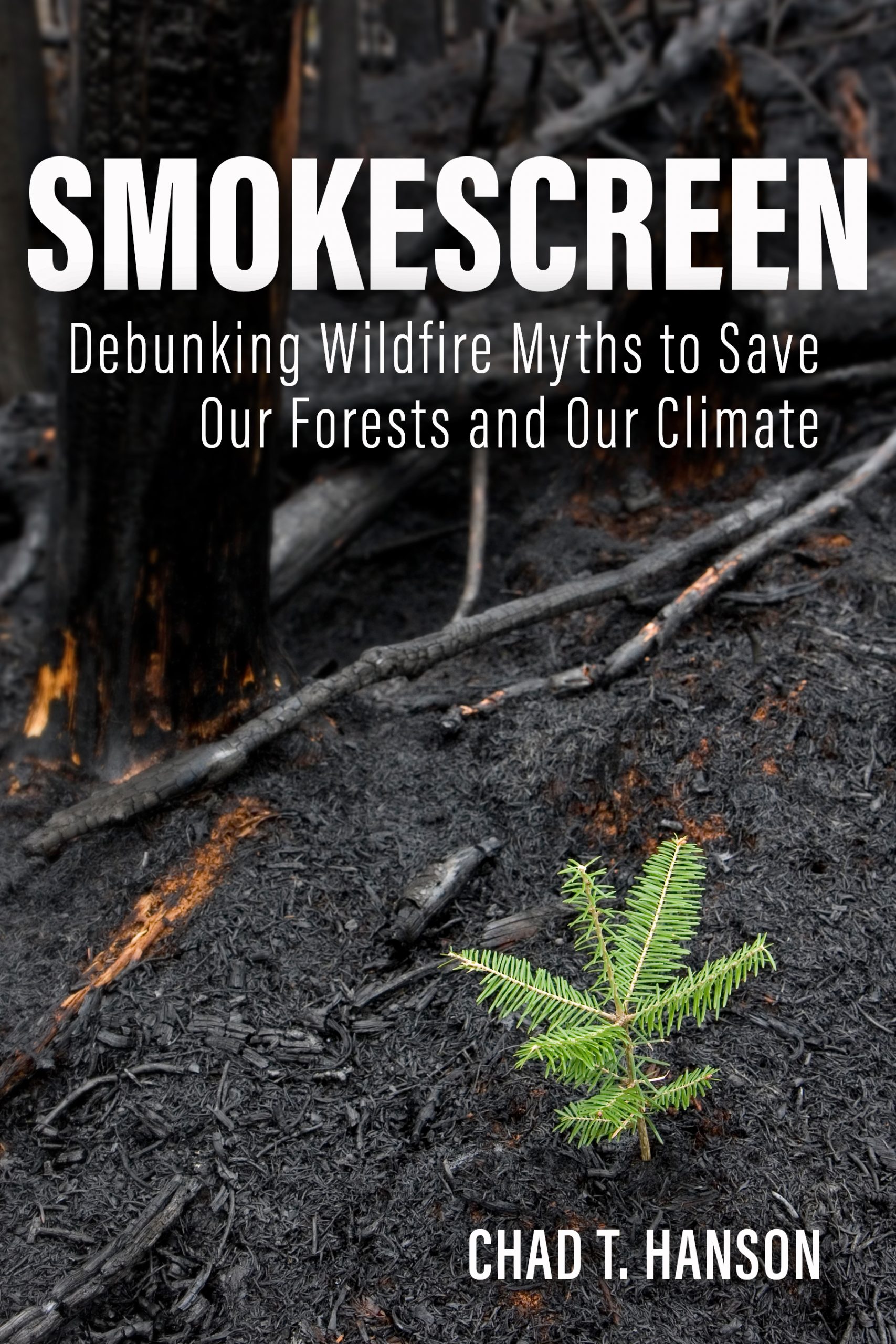

Ecologist Chad Hanson calls his new book Smokescreen: Debunking Wildfire Myths to Save Our Forests and Our Climate, but it could just as well be titled Why We Should Love Dead Trees.

Hanson, director of the John Muir Project, uses the book to explain why wildfires are beneficial to forest ecosystems and why keeping fire-burned trees on the landscape creates a biodiversity-rich landscape that rivals old-growth forests.

Smokescreen, steeped in scientific details and personal stories, is written for the average reader — one who’s likely been primed by media and policymakers to regard wildfires as “devastating” and “catastrophic.”

The book examines why, from an ecological perspective, they’re neither. It also tackles the tough issue of why state and federal resources aimed at keeping communities safe from wildfires often do just the opposite.

The Revelator spoke with Hanson about how logging drives fires, what can be done to keep homes safe, and why protecting forests is crucial to fighting climate change.

In some ways it seems like your book is a PR campaign for wildfires, which get a very bad rap despite their ecological benefits. Why should we learn to value them?

Wildfires in our forests are villainized and vilified in many ways that are similar to how native predators like wolves and bears are villainized and vilified in the media, in movies, and by policymakers.

People have this tendency to think about fire in the forest in the same way they think about fire affecting their home. If their home burns, that’s devastating. And therefore, they think if a fire burns in the forest that must also be devastation. So they want solutions from policymakers. They want people to tell them that they’re going to fix the problem out there somewhere in the forest.

And I think we need to fundamentally shift that perception so that people understand that fire is a natural and beneficial ecological force out in the forest.

We actually have a deficit of fire in almost every forest ecosystem relative to natural pre-suppression levels. The real losses and harms that are happening in communities are almost entirely preventable if we focus our resources and attention near homes, but it’s going to take a 180-degree shift in direction from our current policies.

In the book I mentioned the example of a community that really focused on home fire safety and defensible space, pruning within 100 feet of homes. That made a difference in the 2017 Creek Fire in the mountains in Southern California.

There were 1,400 homes ultimately within the fire perimeter and only five burned. You can only see that kind of success when the focus is on home safety and community protection, as opposed to back-country vegetation management — removing trees, chaparral and other native vegetation — and thinking that’s somehow going to stop a weather-driven fire, which it doesn’t.

One of the things you cover extensively in the book is why logging after fires can be so ecologically detrimental. Why are these so-called “snag” forests of dead trees so important?

Fires, including mixed-intensity fires, have been burning in the forests of this planet for over 350 million years. We’ve had fires, including high-intensity fire patches, in our forests since 100 million years before the dinosaurs walked the Earth. These are deep evolutionary processes, and there’s a deep evolutionary history of dependence and relationships with ecosystems and wildlife species related to that.

And it’s not just fire that burns at low intensity and creeps along the surface. Some species like that just fine, but others like it hot and they need the areas where fire burns more intensely and kills most, or all, the trees in patches.

It turns out that these places where fire or drought or other natural processes kill most or all the trees, these places are not destroyed. They’re not damaged from a biodiversity standpoint. They’re ecological treasures.

These snag forests are oftentimes areas that support the single highest levels of wildlife abundance and diversity in the entire forest ecosystem in a given region, provided that those areas are not subjected to post-disturbance logging — what they call “salvage logging” — which destroys all that wonderful rich complex habitat by taking away those dead trees that so many wildlife species need.

The Forest Service and other agencies engage in post-fire logging and thinning projects that they say will keep communities safer from fire. You point to science that says otherwise. Can you explain?

When people hear the term “thinning,” they think about workers out there with pruning shears and rakes. They don’t think chainsaws and bulldozers, which is the reality of thinning in the vast majority of cases. These are really just commercial logging operations.

“Thinning” is oftentimes a stand-in for what the agencies called “fuel reduction,” which is just another stand-in for logging. The reality is most of the time a thinning project will kill and remove upwards of 60 or 70% of the trees in a given stand. And that includes many mature trees, even oftentimes old-growth trees.

The other thing to understand is that thinning fundamentally changes the microclimate of the forest, and it changes it in ways that make the forest more susceptible to a wildfire, have a faster rate of spread, and a higher fire intensity most of the time.

That’s because thinning reduces the forest canopy cover. When that happens, it creates hotter and drier conditions on the forest floor, because it’s letting through more sunlight. Things are getting more desiccated during fire season.

By removing so many trees, thinning also reduces the windbreak effect that a denser forest has against the winds that drive the flames. So when areas are thinned, the fires can spread through faster.

In the first six hours of [California’s 2018] Camp Fire — between the point of ignition and reaching the town of Paradise and claiming 85 lives and over 14,000 homes — the fire burned through several thousand acres that had been heavily logged in the preceding decade. Some of that was post-fire logging where thousands and thousands of dead trees were removed under the guise of fuel reduction. Some of it was commercial thinning on national forest lands and also on private lands.

Those were the areas that the fire moved through by far the fastest and most intensely.

Outside of those areas, once the fire got into other forests that had no logging history or very limited logging history, it burned overwhelmingly at low and moderate intensity.

If weather and climate are the biggest drivers of fire, how should that inform our response to it?

Yes, weather and climate are definitely the primary drivers of wildfire behavior. In the largest scientific analysis that has been conducted on this question, we looked at the whole western United States — three decades of data, millions and millions of acres of fires — and what we found are two key things. Number one, weather and climate variables are dominant. That’s primarily what drives wildland fires. That means what you do with chainsaws is not going to stop these fires because essentially you’re trying to fight the wind and you can’t fight the wind with a chainsaw.

The secondary finding was that forest management, specifically logging, is also a relevant factor. A lot of people think if you have a denser forest, it’s going to burn more intensely. If you have a forest that’s protected from logging, and therefore it’s going to have more trees typically, then that forest has more fuel and it will burn more intensely. We found exactly the opposite.

Even though weather and climate were the primary factors, logging is a key secondary factor, and it strongly tends to make fires burn more intensely.

How do we better protect forests and value them as a tool for fighting climate change?

In order to really usher in an era of ecological management and climate-friendly management on our national forests and other federal public lands, we need to get the Forest Service out of the logging business. That means we’re going to need to enforce existing laws and we’re also going to need to pass new legislation to accomplish that.

There’s a broad consensus, among climate scientists and forest ecologists in this country and around the world, that moving away from fossil fuels as quickly as possible is absolutely necessary, but it is also not sufficient in order to overcome the climate crisis.

We need to draw down CO2 that’s already in the atmosphere. And the most environmentally beneficial way to do that is to protect natural habitats, especially the carbon-rich ones like forests and wetlands.

That is an essential part of climate solutions. In fact, we cannot succeed unless we do that. And the United States must play a leadership role internationally on this, because more logging [by volume of wood removed] happens in forests of the United States than in any other country in the world.

That puts us in a position of culpability, but also potential leadership to turn the corner.

![]()